… outside school

With clenched fists, shaky legs, and a fear of public speaking, Dr. Amy Honigman delivers her wobbly speech to the Piedmont Community, unable to understand her own words without her thoughts drifting to the possible outcome of failure.

Years later, she confidently stands on the stage of the Zellerbach hall, delivering clear, inspiring speech, to the 6,000 students that greet her.

Although in the short term failure may be degrading, shameful and scary, many people believe that ultimately, success is rooted in failure.

Dr. Amy Honigman, a psychologist at The University of California Berkeley, said the best way to recover from failure is to to be kind to yourself, acknowledge what happened, and then find a way to accept it and learn from it.

“Failure creates motivation and pushes us to think outside of our comfortable box,” Dr. Honigman said. “Everything we know is already comfortable to us, everything we know is inside of these boxes and the only way to get smarter is by increasing our boxes.”

Music assistant Jan D’Annunzio strongly believes in this idea, while also fully understanding the panicked feeling one gets from failing, or the fear of it.

D’Annunzio said she has been terrified of playing piano in front of an audience since a young age, concerned that she may make mistakes, or not meet others expectations.

D’Annunzio said her greatest take-away is that under any circumstance, without risking failure, then failure is automatic anyway because there’s no opportunity for success.

“There is no fault in failure,” D’Annunzio said. “It does not mean you are a bad person, it just means that you have to get up and try something different next time.”

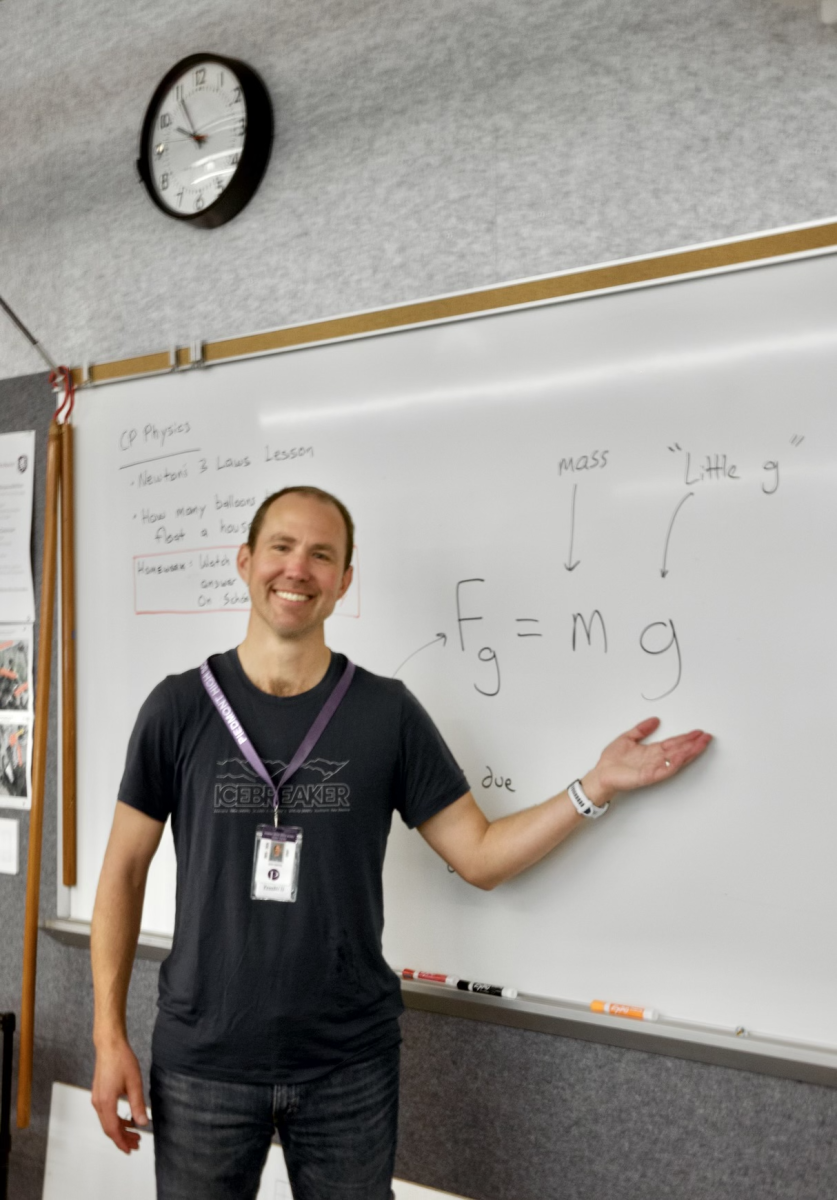

Math teacher John Hayden, who researched the differences between growth and fixed mindsets for his doctorate degree, believes in looking at instances of failures as a chance to grow instead of labeling yourself as a failure. In the spirit of this belief, for students who fail tests because they cannot grasp material, Hayden likes to remind them of where they were two months ago compared to what they have learned and can do now.

“The research shows — and experience shows — that it’s when we fail, pick ourselves back up, and learn from it that we have the most growth as people,” Hayden said.

Alisa Crovetti, Ph.D., Psychologist and Clinical Supervisor at the Wellness Center said that the healthiest response to failure is to evaluate the situation and be realistic about how difficult it was rather than blaming themselves.

“If someone attributes a failure to some sort of innate quality that they have that’s unchangeable, that’s really kind of a helpless orientation,” Crovetti said.

Junior Lulu Tellez, who learned that she did not make Advanced Acting last spring, said she had a hard time recovering from the disappointment. She was told that she had the talent but lacked the dedication to be in the class.

“That showed me that not succeeding wasn’t the end of the world,” Tellez said. “I tried something and enjoyed it and in the end, it didn’t pan out, but I was still really glad I did it.”

Because she began to tame her fear of failure, she felt more open to introducing risk into achieving her goals.

“I’m not somebody who takes a lot of risks,” Tellez said. “I weigh my options and my chances and I don’t really do things unless I have an inkling that I’ll be able to succeed.”

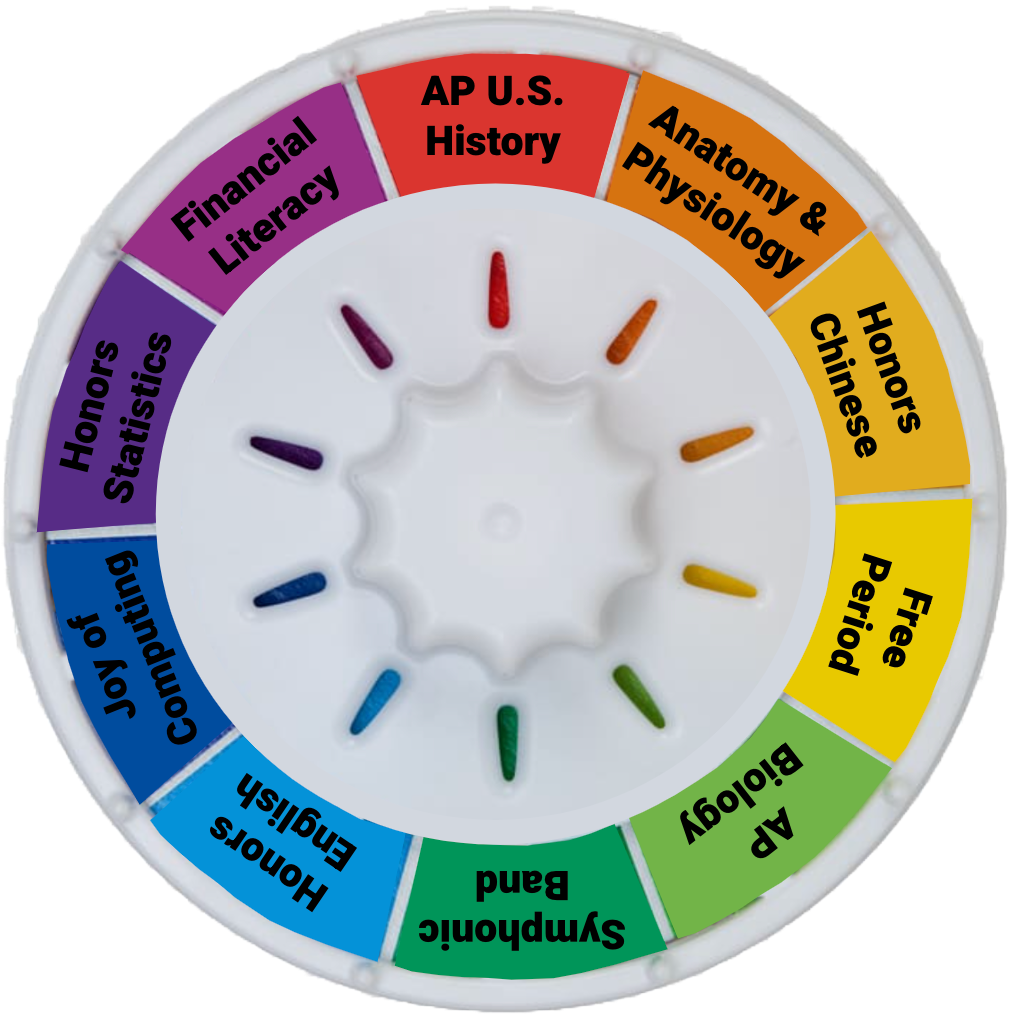

Without acting, Tellez now has room in her schedule in and out of school for music in the form of piano lessons, AP Music Theory and Troubadours.

Her decision to audition for the Troubadours came after the realization that she could recover if she did not earn a spot. She had wanted to be a member since middle school, but until this year decided not to audition due to the fear she would not be accepted.

“I took a chance, and I knew that I [might] not make it, but it was something I wanted to do so why would I not try out?” Tellez said. “I think the whole acting experience helped me with that.”

Two student athletes, junior Elijah Levy, and freshman Gracie Ellis, have both experienced obstacles that come with athletics; however, both recognize the positive aspects that come with failure.

Levy, a cross-country runner, was injured during the season, which restricted him from running at his full potential. Despite negative aspects of his injury, he believes that each failure is worthwhile in some way.

“I believe that everything amounts to something,” Levy said. “Even something as simple as an improvement in my pain tolerance.”

Freshman Gracie Ellis, the goalie for the varsity soccer team, says she feels a lot of pressure as the last person that can save the ball from going into the net.

“It’s hard not to lose self-confidence,” Ellis said. “When the ball goes in, it’s pretty hard for me to come back from that.”

Ellis says the best way to recover from the other team scoring is to do something positive that compensates for the failure, such as making a good save.

“I think failure makes the positives, such a saving a goal, feel a lot better,” Ellis said. “Even though it’s stressful, I really love it because of how rewarding it is.”

Successes can be even more joyous if students choose to be less private with failures, senior Gianna Massullo said.

“People should be proud of their accomplishments, but also more open with their failures,” Massullo said. “Everyone has failures and that’s a great thing because that means you’re human.”

Tellez said that regardless of what grade she ends the year with in AP Music Theory at the end of the year, she will be glad that she decided to sign up for the class despite her minimal background in theory.

“I go back and forth. There are some days where it’s just like, ‘This is such a mistake, what have I done to myself?’” Tellez said. “Other days I’m like ‘Wow, I’m learning so much new stuff. I’m growing as a person. I’m struggling then pushing through and then succeeding or not succeeding.”

… in school

“You’re getting Cs on this stuff, and dear Lord, you’re getting Cs in junior year. You’re applying for colleges next year,” math teacher John Hayden told his son.

For years, his son would sit in classes that were too easy for him. Even by junior year, he was still spending class time teaching his peers how to do the work. Every night, he would do calculus homework with his mom, a former calculus teacher, and prove to her he grasped the material. But when it came time to take tests, he would unfailingly get Cs and Ds.

“[Junior year] was probably the hardest year of his life for us because we knew what his potential was, and his grades were not reflecting that,” Hayden said. “There were a lot of times where we pushed him too hard and in the wrong direction.”

Hayden’s own experience of his son’s high school years changed his perspective on the grading system and raised questions about what constitutes failure. Hayden began to reconsider how he teaches his classes.

“That’s another piece that’s really flipped my thinking on grading and education, was watching my son struggle and saying, ‘Wow, in what ways am I perpetuating this with my own students?’” Hayden said.

Math teacher John Hayden said that the A through F system was originally designed to give feedback in which students fall on a spectrum. Grades also indicate how ready students are for the next level of that subject.

He has noticed that in Piedmont, the overall perception is that success is getting an A in all classes. In other high schools he has worked in, on the other hand, some students recognize that success can come in the form of a C if they put in the effort to achieve it.

“If something is really hard for you and you’re able to overcome whatever challenges are in front of you, a C should be looked on as, ‘That’s awesome because you really persevered,’” Hayden said

The current grading system and the culture surrounding it have a major fault when it comes to students that struggle to grasp concepts: they may come to see the grade as a label that defines them, Hayden said.

“It’s very difficult not to see your self-worth as defined by these labels being placed on us,” Hayden said.

Junior Lulu Tellez said that the word ‘failing’ is used too often when students talk about tests and classes, even when they get a B or C.

“A lot of the time they didn’t [receive an F] and that just brings the standard up a lot higher because people say, ‘Ugh, I failed this test, I got a B,’” Tellez said.

Crovetti agrees that calling a B or C a failure creates a level of stress that is not healthy for most students. If asked whether they actually failed, she said that most will say they did not.

“Teenagers and people in general like to speak in hyperbole,” Crovetti said.

Peer-to-peer comparison of academics inaccurately measures one’s capabilities because intellect is just one of a multitude of factors affecting grades, senior Gianna Massullo said.

“Your grandpa could have died and your cat ran away and you have a test the next day and now let’s say you get an F on the test,” Massullo said. “That’s not really getting an F on the test. That’s getting an F on being able to do things while very emotionally distraught.”

Hayden allows all tests he gives to be retaken at a later date, which has reduced anxiety in some of his students because they know they will have a second chance.

“In my opinion, every time we decide to give a test, it’s an arbitrary date,” Hayden said. “We’re done, so we’re going to test this now. That doesn’t mean you’re ready for it. It doesn’t mean if I couldn’t give you three more days to practice that then you wouldn’t have it.”

Sophie Baker, a senior who transferred from Groton School, a boarding school in Massachusetts, knows just how uncomfortable failure can be. Not only did Baker have trouble adjusting to the social aspect at Piedmont, she was placed in classes that were completely different from her classes at Groton.

“[The transition] was really difficult for me in all aspects,” Baker said. “I feel as though I have failed at Groton because I was not able to keep up with all of the things that were happening in my life but looking back on it I understand how leaving was the right decision.”

Due to student competition, there is a strong fixation on this idea of perfection, however, many people, including Honigman do not believe in the benefits of perfection.

“Perfection is boring and resilience is exciting,” Honigman said. “I respect resilience!”

Dr. Honigman said that the pressure high school is putting on students to get good grades to get into the best college is taking away from really learning and finding one’s passion.

“It’s important for people to have meaningful values for themselves in order to do well, but doing well is not the only important thing in life,” said Dr. Honigman. “There are other many important things like finding who you genuinely are and what you’re passionate about.”