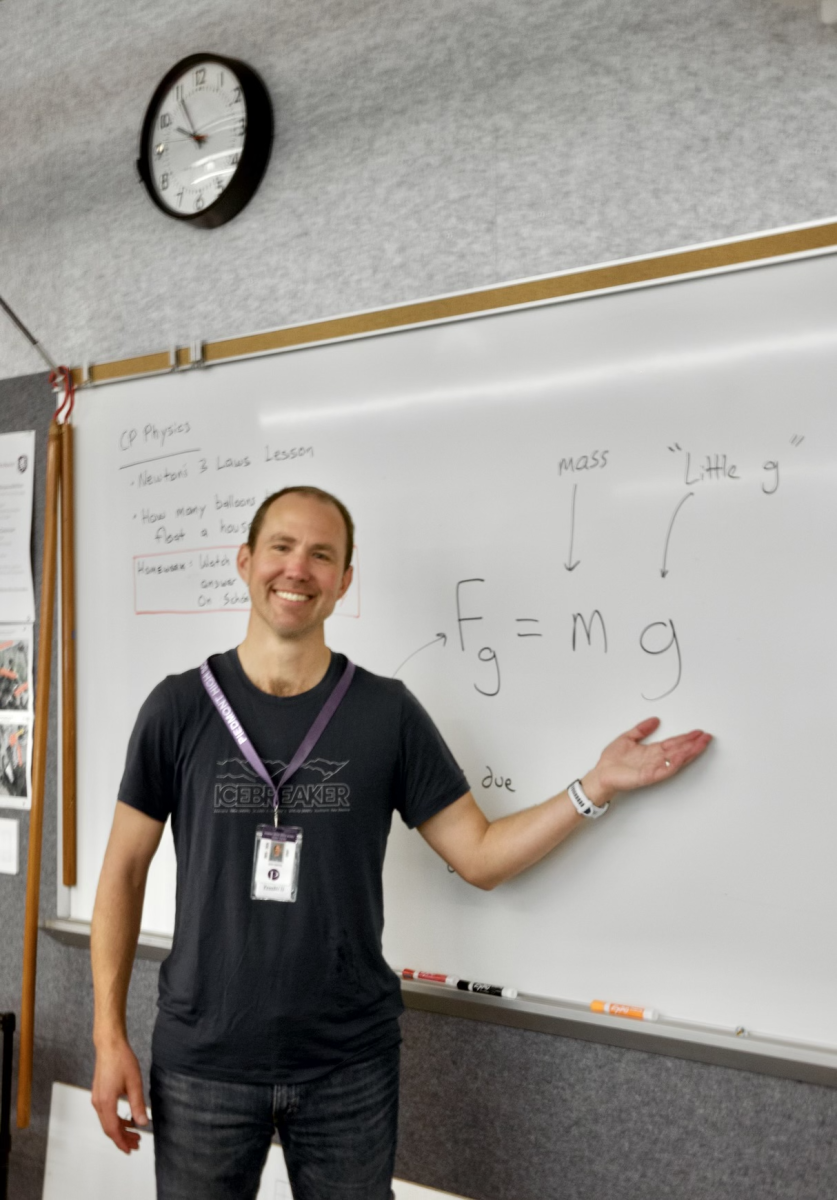

New country, new school, new people, new sport — Italian exchange student junior Alessandro Spazzini is dealing with all of these when playing on the junior varsity men’s water polo team in his first year attending PHS.

Coming to PHS, Spazzini decided he wanted to play a sport. He was actually leaning towards running cross country, but on impulse chose water polo.

“Water polo seemed more fun since I’d never played team sport before,” Spazzini said. “There’s more of a chance to meet other kids and make friends within the team. I’m really happy with how it turned out.”

One difficulty Spazzini encountered when he began playing on the team was with language: although he had been learning English since fifth grade, Spazzini could not understand any of the specific water polo terms that his teammates used.

One difficulty Spazzini encountered when he began playing on the team was with language: although he had been learning English since fifth grade, Spazzini could not understand any of the specific water polo terms that his teammates used.

“Now I have a sort-of brain dictionary of those words’ meanings,” Spazzini said. “When we play in games, if the coach screams something, I can understand and do it.”

Spazzini picked up the game quickly, but still experienced many of the same difficulties as other first year players, said men’s water polo coach John Savage.

“His English is very good, so it hasn’t been that much of an issue,” Savage said.

Spazzini plays goalie for the junior varsity team and is the back-up goalie for sophomore Jack Bocheff on the varsity team.

“I like being goalie, you’re by yourself and you just need to follow directions,” Spazzini said. “You can get a strategic view of the game.”

Spazzini was a good fit to be goalie because of his long arms, Savage said.

“It’s a high pressure job, because he’s responsible for both offense and defense: obviously for stopping shots as they come in, but, after he stops a shot, to make the appropriate pass and a fast break,” Savage said. “Imagine if you’re a quarterback and all you had to make are deep throws. It’s high risk, high reward.”

Varsity water polo captain senior Colin Dixon said Spazzini brings a positive attitude to the team.

“When everyone else is down, for some reason he’s the only one smiling and being happy,” Dixon said.

Not only was water polo new for Spazzini, so was the concept of school sports. The way sports work for high school students in Italy is different: only club sports not affiliated with schools exist and, while it depends on the level of play, sports can interfere more with school work, Spazzini said.

“People complain that becoming great at a sport in Italy is really hard, because if you want to be good, suddenly you have to give up school,” Spazzini said. “Here, since it’s managed by the school, they know how much work the students have outside of the sport and manage to create easier programs for the students. The balance between sports and schools is generally better.”

Even attitudes about sports are different in the United States.

“In Italy, we don’t do speeches or sing to get pumped up,” Spazzini said. “Here, everything is more showy, but in a good way. Like for Halloween or Christmas, how people put up decorations, at football games, there’s a band and cheerleaders, and people want to show more excitement and enthusiasm about sports.”

Spazzini went to his first American football game with the team, Dixon said.

“He was surprised by the amount of cheering and how energized the atmosphere was, like a soccer game in Italy but with a more constant buzz,” Dixon said.

Outside of sports, Spazzini’s experience studying abroad came with other changes. For example, compared to Sesto Calende, the town in northern Italy where Spazzini lived, Piedmont is a less urban environment, with fewer shops and restaurants and less-frequented public transportation, he said.

“I would say people are kind of generous here, but not in terms of material things, like they don’t give me money, but like for rides home and general kindness,” Spazzini said.

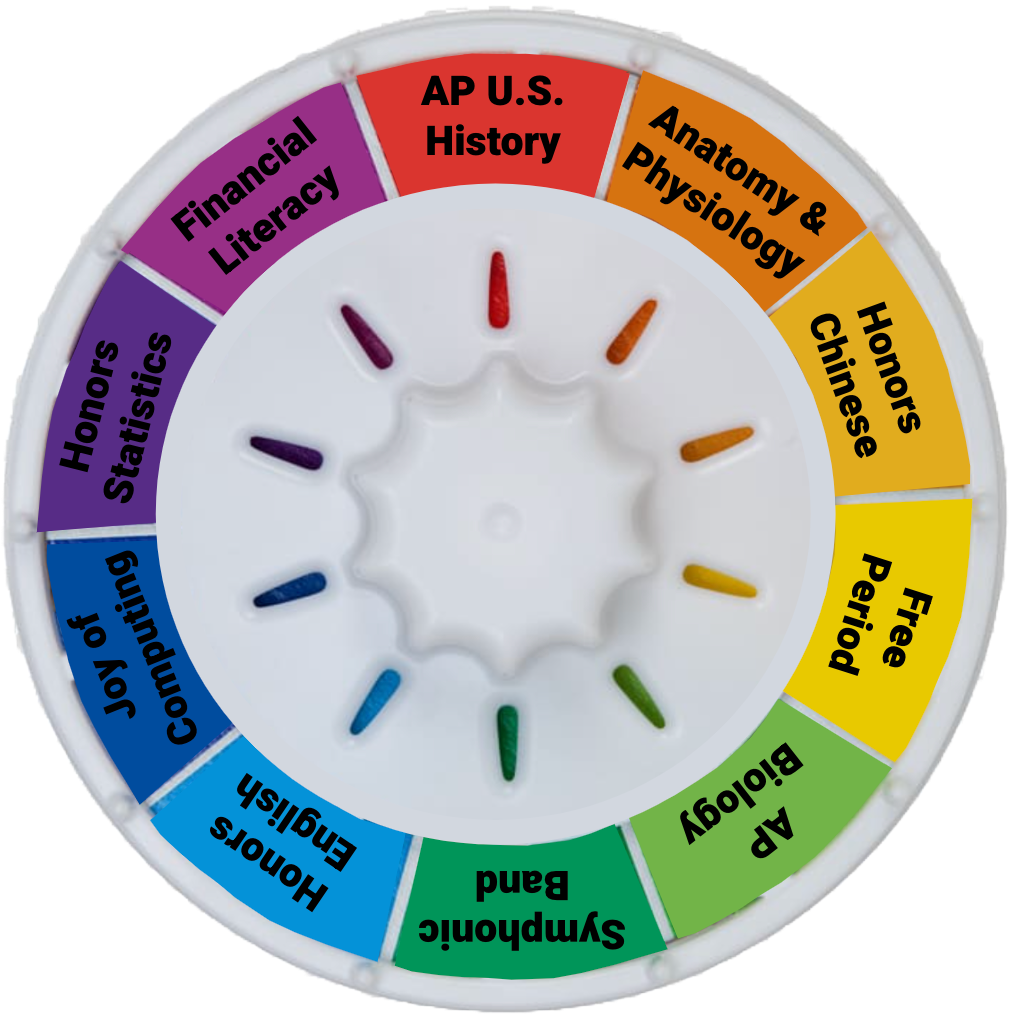

Another difference between the United States and Italy is in school systems, Spazzini said.

“With seven classes a day, it’s much more stressful in Italy, and here it’s more chill, more relaxed,” Spazzini said. “You have more time, you can ask your teachers whatever you want, whenever you want. You have the opportunity to do a good job.”

In adjusting to all these differences, Spazzini says he has settled into his classes, without any major problems with language.

“Everyone is nice and tried to explain to me all the processes and methods that they use,” Spazzini said. “Obviously, all the kids here are used to a certain way of doing things that’s totally different from mine, so I had to get used to that. But now I think I’ve filled the gap a little bit.”