Twenty-four students stare groggily back at Economics teacher Gabrielle Kashani as she introduces the student who will be presenting their current event. On the other side of the screen, some students are shoveling down their breakfast while others are brushing their teeth. They are in offices, on porches, and in beds, disconnect present in every face. Flipping to the last slide, the presenter asks the first discussion question. The red mute signs slowly begin to disappear, and Kashani lets out an inaudible sigh of relief.

For students, distance learning has meant more freedom. For teachers it brings new lesson plans, less time to interact with students, and more work overall.

“We’re still beginning class with the current event, and students are, to some extent, participating,” Kashani said. “I feel like that’s the most interactive and dynamic part of class.”

Kashani said that current events are presentations put on by students and have been occurring since the beginning of the second semester. She is thankful that this activity translated so easily into her distance learning curriculum because, like other teachers, it has been hard for her to keep all students engaged.

“Distance learning can not and does not replace in-person learning,” Kashani said. “[It can not and does not replace all] the connections and personalities and humor and nuances and intricacies of all dynamics, not only between the teacher and the students but also amongst the students.”

Like Kashani, Math teacher Amy Dunn-Ruiz has found distance learning as a whole to be ineffective due to the fact that certain students depend on in-person learning more than others.

“Some students have weathered it better than others and that has nothing to do with whether they’re a good student or not,” Ruiz said. “I’ve seen across the board kids who typically are on top of all their work really having a hard time missing the personal connection and missing the motivation that they get from their teachers and their classmates.”

However, the majority of students are succeeding in the virtual learning pass/fail environment. Spanish teacher Virginia Leskowski has found that although some students require a little more extra help, most of them are rising to the challenge.

“I am very impressed with most of my students,” Leskowski said. “I always say that you can either be committed to ignorance or intelligence and it is clear that my students want to learn.”

Not only are students stepping up. Most teachers also are switching up their lesson plans to accommodate for the virtual platform, which has been difficult and time consuming, Dunn-Ruiz said. She does not think she would have been able to teach students as efficiently without the other teachers’ support and community.

“On the surface, it should be easier,” Kashani said. “But definitely changing how I do the class, and the homework I assign [is challenging].”

In addition to changing the curriculum, teachers also have to spend more time grading homework for accountability, Kashani said. Before, the majority of teachers’ work was in the classroom, but now teachers only see their students for about an hour every week. Therefore, they are having to grade a lot more at home assignments, which takes more time.

“I’m spending more time grading than I normally do,” Kashani said. “That’s not, to be frank, the fun part of my job.”

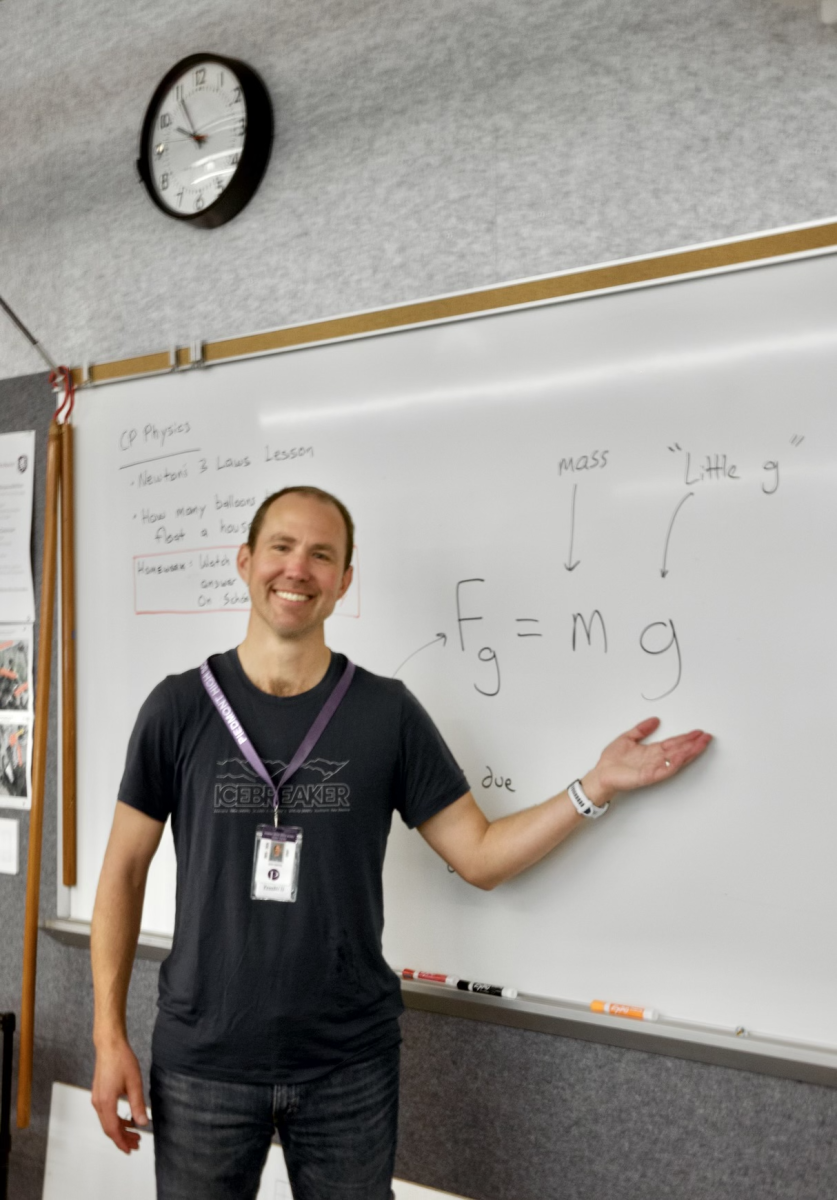

Like most teachers, Kashani misses the human interaction side of teaching. Unlike in the classroom, it has been harder for her to gage students’ understanding in addition to their quality of work.

“I can tell by the conversations going on whether you guys get it, or you need a little infusion of a hint,” Dunn-Ruiz said. “I know what level of help to give.”

It is difficult for teachers to know what is going on with their students, not only at school but in their personal lives, Leskowski said.

“I feel like that was the biggest thing missing was the interaction and us supporting each other,” Dunn-Ruiz said. “While people did sign on to my calls and I was able to have those conversations, they were just not nearly as impactful and special as when we were all in the group doing it together last year.”

However, Leskowski has noticed that her check-ins have more meaning because of the gravity of the pandemic and how the classes are often her students’ only chance to see their classmates.

“People are always checking in with each other but now those check-ins mean something more,” Leskowski said.

Dunn-Ruiz said that she was thankful that she already had connections with her students from the first semester. From the start she already knew how to motivate her students in different ways.

“Going ahead into the new school year, should we start off virtual, I’m going to need to really put effort into making sure I connect with my brand new students,” Ruiz said.

Unlike Leskowski and Dunn-Ruiz, Kashani has not gotten the chance to connect with her students over the first semester because she teaches Economics, a semester course. Additionally, she has never taught most of the students in her class before. She definitely feels that effect on her relationship with her students. However, she thinks it helps that she is teaching a course very relevant to the world today.

“Obviously, I’m not happy that we’re in a downturn,” Kashani said. “But in a strange way or in a perverse way it’s a little bit exciting. What I’m theoretically teaching about is actually being conducted and engaged and activated in a very public way in real time.”

Kashani encourages all students to take this opportunity to extend their learning outside of the classroom.

“Just like COVID exposes the weaknesses in the body’s system, COVID has also exposed our other weaknesses including in the economy,” she said. “It’s an interesting time to reflect on family, on work, on health care, on the structure of the economy, and on class. Look at what’s broken and consider how you can engage and make some of these dynamics better, not only within your own family but in your community.”

Kashani said that the lesson that students and teachers are learning about flexibility is going to be one of the most important lessons of the semester.

“You might do a job 10 to 15 years from now that doesn’t even exist today,” she said. “You are going to consume technology, you’re going to consume resources in ways that haven’t been thought about or developed today.”

Although Google meetings might be our future, Dunn-Ruiz said that she wants to remind the community that these are unprecedented times.

“We’ve been doing triage, which is a fancy word for crisis management that nobody, nobody’s curriculum was set up for,” she said.

But above all, she wants the community to know that teachers are there for their students and are trying their best.

“In terms of virtual learning, I want people to know that as an educator, I am still 110 percent dedicated to my subject area, my courses, my students, my department, the school and the community,” Kashani said. “Just because I’m not physically there doesn’t mean that my care for any of those things has changed.”