“How are you guys feeling?”

“How are you guys feeling?”

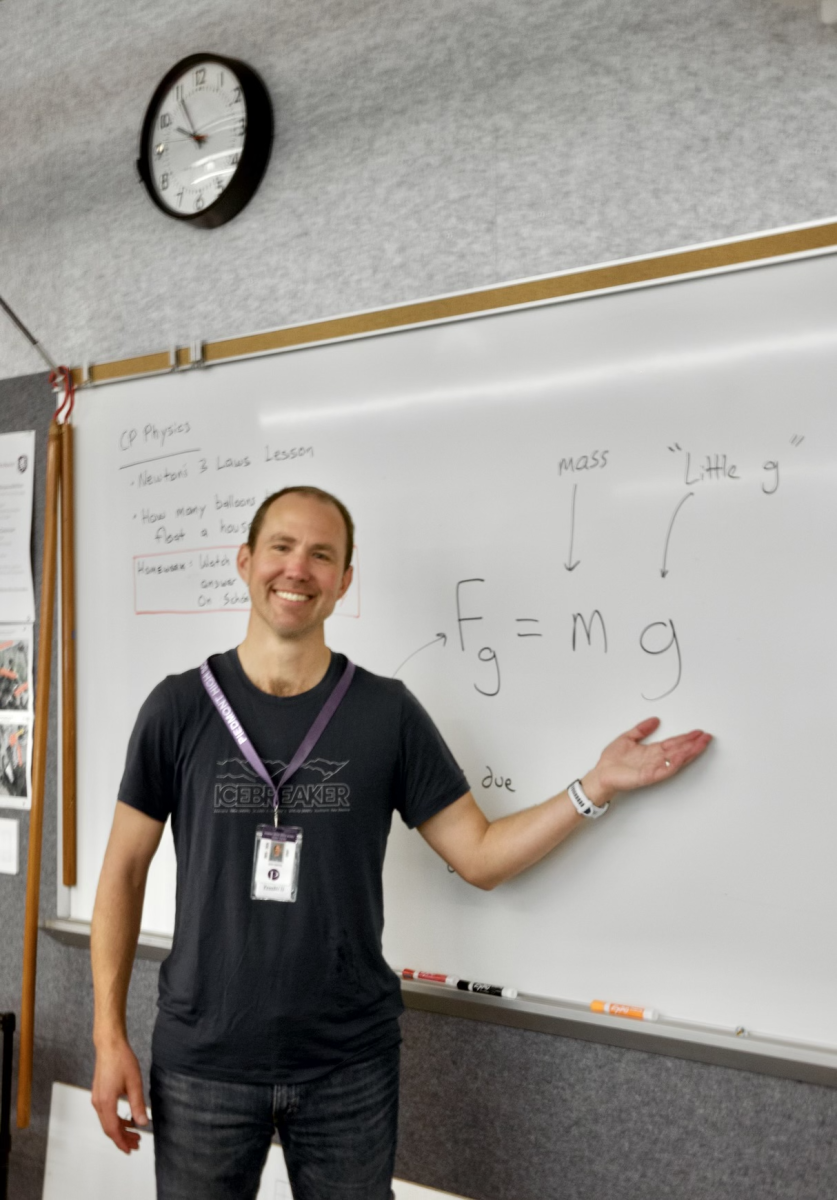

Across the Google Meet screen, students timidly lift a thumbs up, a thumbs down, or something in between. They then promptly return to taking notes, listening to a lecture, or finishing the classwork.

But it is clear that this semester, students and teachers have all been harboring feelings of distress that go far beyond a simple thumbs down. This overwhelming hopelessness stems from a build-up of heavy national, local, and personal stress over this past year. With the end of the semester approaching, it is unrealistic to expect finals to look like they do in any other year. We cannot simply ignore that students, as well as teachers and administrators, are handling an incredible amount of pressure beyond school, and ways of assessing students’ learning must reflect this.

Why now?

TPH isn’t alone in suggesting change. This past Thursday, ASB met with principal Adam Littlefield and assistant principals Erin Igoe and Irma Muñoz to voice their concerns. In a meeting that spanned two class periods, ASB students took turns sharing their raw and honest experiences from this past semester, emphasizing that their emotions are reflective of the student body they represent—and that we need help.

“Never in my 37 years as an educator have I seen so many distraught students in one setting,” Littlefield wrote in an email to teachers on Friday. “[T]hey have reached their saturation point.”

Parts of the discussion focused on the pressures of upcoming final exams, which are in an abnormal online format this year that varies from class to class. ASB proposed several changes to final exams that Littlefield encouraged teachers to consider, such as making exams pass/fail or giving students the choice to not take them. As of publishing this editorial, at least one teacher has already made their exam optional.

“Students are pleading for help and want to be part of the solution,” Littlefield said. “I cannot direct you to change your final examination practices. I do ask, however, that you consider the requests they have made.”

After analyzing the situation and meeting with ASB members, TPH is proposing our own, simple plan that we think will give students grades that accurately reflect their work, while minimizing disruption to teachers, grades, and assessing learning. We desperately urge that teachers, students, administrators, and community members take the time to read our full solution and detailed justifications.

Our proposal

For the approaching finals week, we first suggest that teachers consider:

- Changing the grading scale for their final exams and final projects by shifting the scale by one increment

- In a class with a percent-based, traditional grading system, this would mean a shift of 10 percent higher, or one full letter grade.

- ex: a 75% or a C on the final in a points-based class would count as an 85% or a B.

- In a class with a standards-based grading system, this would mean a shift to one higher standard.

- ex: a “Developing” grade or a 2 on the final in a standards-based class would count as a “Proficient” or a 3.

- In a class with a percent-based, traditional grading system, this would mean a shift of 10 percent higher, or one full letter grade.

This works similar to how weighted classes used a shifted GPA scale. With the understanding that the rigor of courses schoolwide has increased in our new online environment, almost all students and teachers bear extra weight in this year’s classes.

We also strongly urge teachers to consider:

- Making examinations open-note

- It is borderline impossible to ensure that all students maintain the standard of academic integrity that teachers and administrators expect.

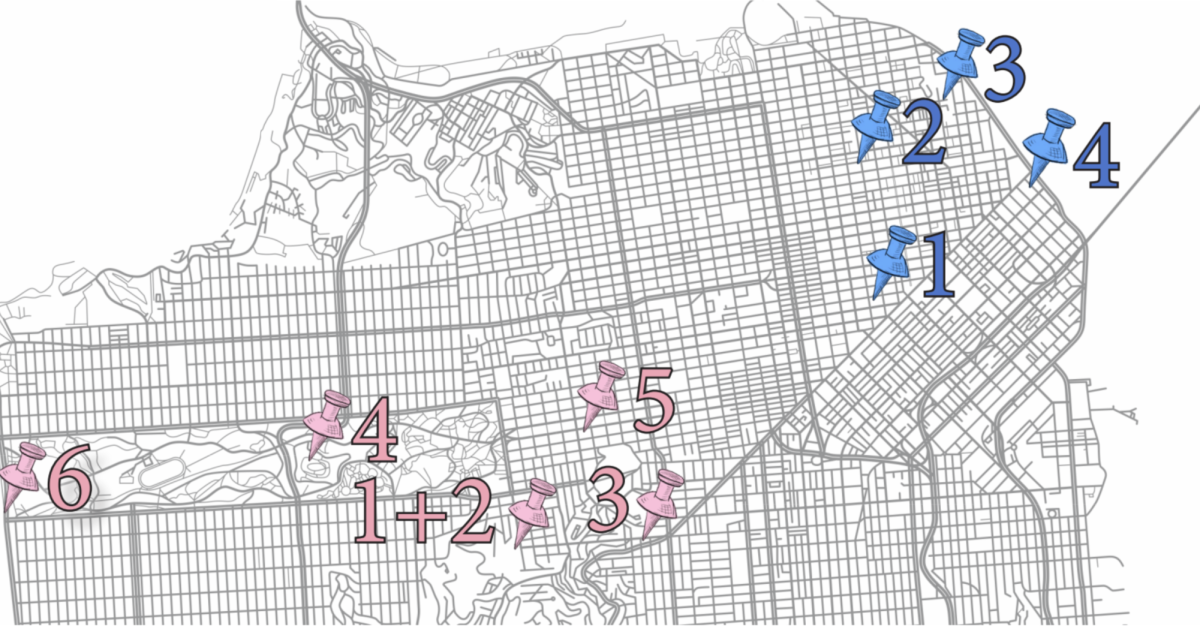

- Last February (during in-person), 89.3 percent of students taking four or more AP courses had cheated in the last month. This number is undoubtedly higher given higher stress and worse test security now.

Allowing students to look at their notes does not compromise the level of understanding teachers expect from them. Instead, it prevents students from having to violate academic integrity to feel adequate in a learning environment that no one has previously experienced.

In our November editorial, we addressed these downfalls of academic integrity and proposed viable alternatives to traditional testing, and the issues we saw then still remain.

Shifting the grade scale and making exams open-note will not disrupt finals or our assessments of student understanding. Unlike college courses that are centered only around midterms and finals, students have already been tested consistently throughout the semester, and their learning has already been reflected in unit tests and projects along the way. There is no harm to make these small adjustments, and none of the exam questions that teachers already have spent hours writing will go unutilized.

Why we want change

As many have said, this school year is “unprecedented” for teachers and students. We have experienced the isolation and fear of the pandemic, while becoming increasingly fatigued by distance learning. On top of that, we’ve endured the chaos of the presidential election, massive fires, large protests, and found ourselves struggling with a multitude of worries and distractions. This school year, it has become progressively more difficult to prioritize our studies.

Throughout this semester, students have been determined, holding themselves to the highest standards in their classes and attempting to suppress the constant loneliness and anxiety they are experiencing. In a normal year, students had already struggled to subdue the stress of rigorous classes, but with the addition of unusual and taxing circumstances outside of school, this stress is only heightened.

On Wednesday, students were forced to reckon with yet another national traumatic event: the insurrection and attempted overthrow of the United States Capitol Building. Piedmont students have been raised to understand the value of democracy, and we’ve been taught that the United States is the prime example of how a government should function. This week, our trust in such democracy vanished as we watched rioters breach the Capitol Building. Students attended their classes for the rest of the week, but our minds were in another place as news rolled in of deaths, impeachment, arrests, and statements from politicians in response to the event. This event became the final straw in a school year marked by loss.

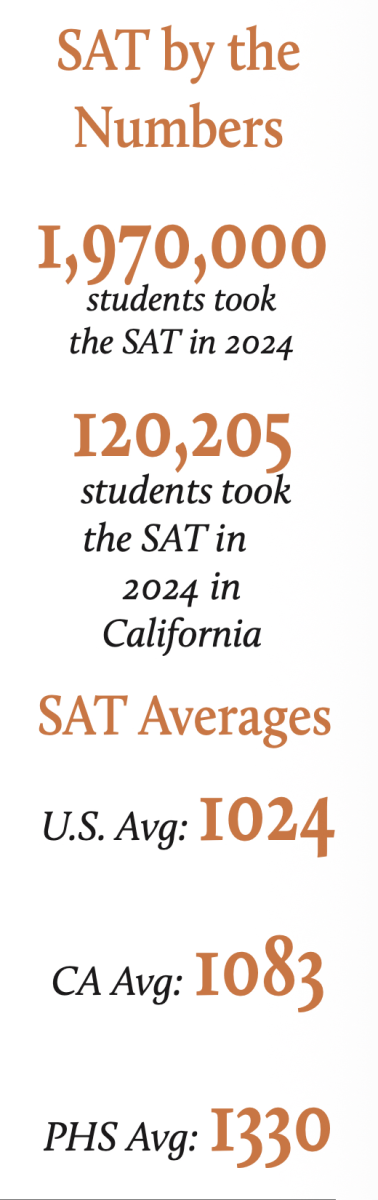

We thank the teachers who provided us with class time to process these events, as it was nearly impossible for many of us to focus on academics during such a time. We lack the perspective that adults have and are overwhelmed as we try to plan for the future when it has become so unpredictable. With little life experience and no reference for how our world should function, this claustrophobic state feels like it will last forever, adding to the existing worries that high schoolers would face in a normal year: extracurriculars, SAT prep, family-related stress, college applications, and of course, the constant pressure to succeed in school.

We know that high school students are not alone in many of their struggles right now. When looking at a screen of faces (or even a blank screen with cameras off), it’s difficult to not feel our teachers’ pain. We absolutely do not want to create more work or stress for teachers. We are so thankful for our teachers who show up every day and talk to a silent screen, who make sure we learn, and who find fun ways to keep us engaged. We are not taking that for granted, but only recognize that it is impossible for anyone to perform at the level they usually would.

This is especially true considering that we have lost learning time in our distance learning schedule. Students that have regular, seven-period schedules have lost 350 minutes a week of direct interaction with their teachers, which has amounted to roughly 110 hours this semester. Our regular opportunities to reach out for assistance have been severely reduced. Changing finals would account for these disruptions.

We also try to understand that school is not about the grades. In fact, tests are ways for students to gauge if they have mastered material and for teachers to assess how well students have learned. Therefore, it makes even more sense that we lighten the pressures of finals; no one knows how we are expected to perform in distance learning mode. There has been no precedent, so following our plan would give PHS the chance to examine student performance without punishing students and disheartening teachers for the uncontrollable challenges we are facing.

The Piedmont community encourages student involvement. So, from the students’ perspectives, to answer the question: “How are you guys feeling?” This is our collective voice, bigger than a thumbs-up or thumbs-down, to sum up the painful experiences from this semester. The power for relief lies in the teachers’ decisions. We hold onto a collective hope that teachers will be able to make these slight adjustments in our final exams and projects. Distance learning has always been called a “work of progress;” now is the time to progress together.

TPH Editorial Board & ASB Class