I am speaking with a twenty-year-old who has tested out of his college language requirements. He passed the AP Spanish exam in high school, and has been deemed ‘proficient’ in the language by the university he currently attends. The use of the word proficient in this context is laughable, as the person standing in front of me speaks incomprehensibly, abides by few rules of grammar, and uses elementary vocabulary.

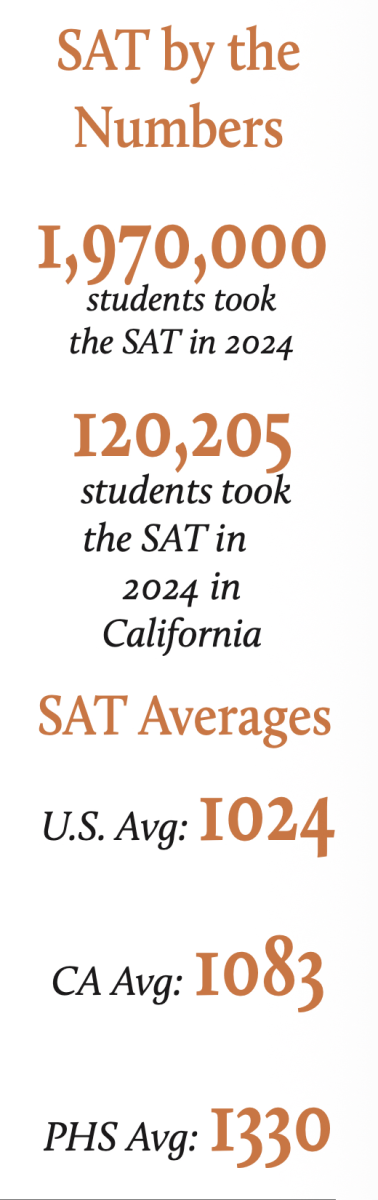

The United States is an infamously monolingual country, but this is unsurprising. Our students are not to blame; this is not a matter of effort on their behalf. They are being failed by our education system, and the culprit is the late age at which they are being introduced to foreign language study. The vast majority of Americans are first exposed to a foreign language their freshman year of high school, or sometime in middle school at the very earliest. At PHS, the language requirement for graduation is just three years. Achieving fluency by means of sporadic instruction over a three to four year period during the late teenage years is inarguably unachievable. According to a 2018 MIT study, the most optimal time to learn a new language and achieve fluency is before age ten. A 2020 UCLA study found that the brain systems in charge of language learning have accelerated growth from six years old until puberty. By introducing students to language far past the age at which their brains are suited for learning them, we are setting them up more for frustration than success. Purdue University researchers found that a host of beneficial traits are strongly associated with learning a second language: improved attention span, creativity, and memory; boosted brain stimulation, multitasking skills, and self-esteem; and an improved first language. Successfully teaching our students another language is a goal we should be prioritizing highly.

In order to implement an alternate program that would produce students who can reap all the benefits of learning a second language, the US would need to make considerable adjustments to the structure of public elementary education. A change as drastic as this one would be expensive and complicated. Critics of implementation of national foreign language programs at the primary school level argue that there is little existing structure to accommodate such a change. Most elementary schoolers are taught by an individual teacher. Hence, in order to integrate language instruction into their curriculums, schools would either need to institute requirements of knowledge of a foreign language for all of their teachers or hire a separate teaching staff specifically dedicated to language. The US also faces a unique struggle that few other countries face: the lack of an obvious choice of second language. Whereas in many parts of the world English is often learned as a second language, most public American schools offer at least three foreign languages, as students have varying preferences as to which language best suits their needs.

While these challenges are significant, they are not insurmountable. The potential communal improvement far outweighs the monetary and logistical costs of implementing a plan to eliminate monolingualism. As we progress as a country towards this goal, obstacles like the struggle to find staff qualified to teach a foreign language will self-eliminate. The return on this investment will be great. Most former language students will, upon reflecting on their present language skill, pride themselves on the fact that they can ‘order a beer’ in their language of study. We should strive for a better level of fluency than inconveniencing the resort over summer vacation in failed attempts to impress them with our inadequate margarita-ordering skillwaitstaffs.

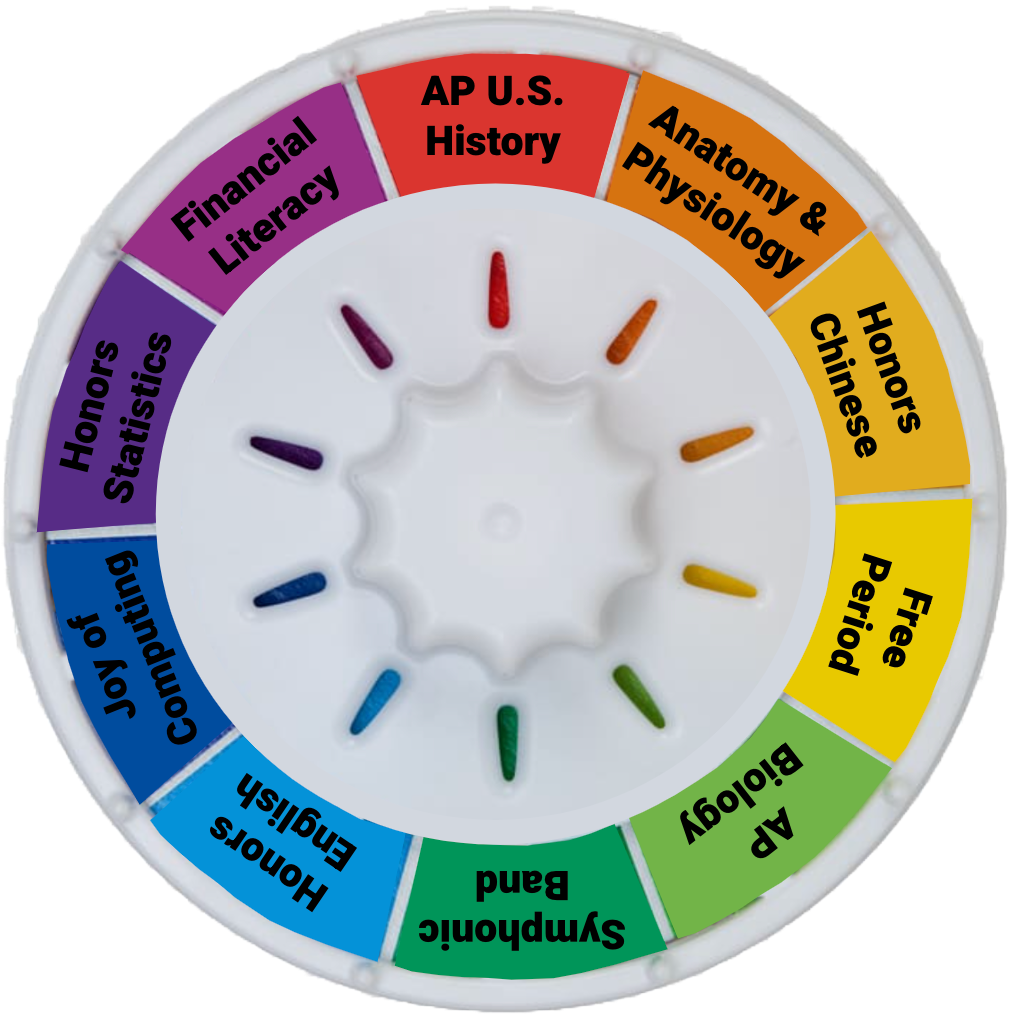

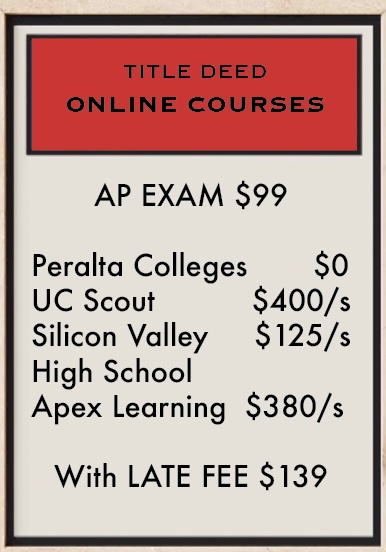

Due to online learning, TPH chose not to run the course selection guide this year, but still wanted to offer suggestions for next year’s schedule