Like the Spanish Flu or wired earbuds, book bannings are now viewed as distant history. However, book bannings, the practice seen throughout history– during the Civil War, the Holocaust, and the Civil Rights Movement– still persist.

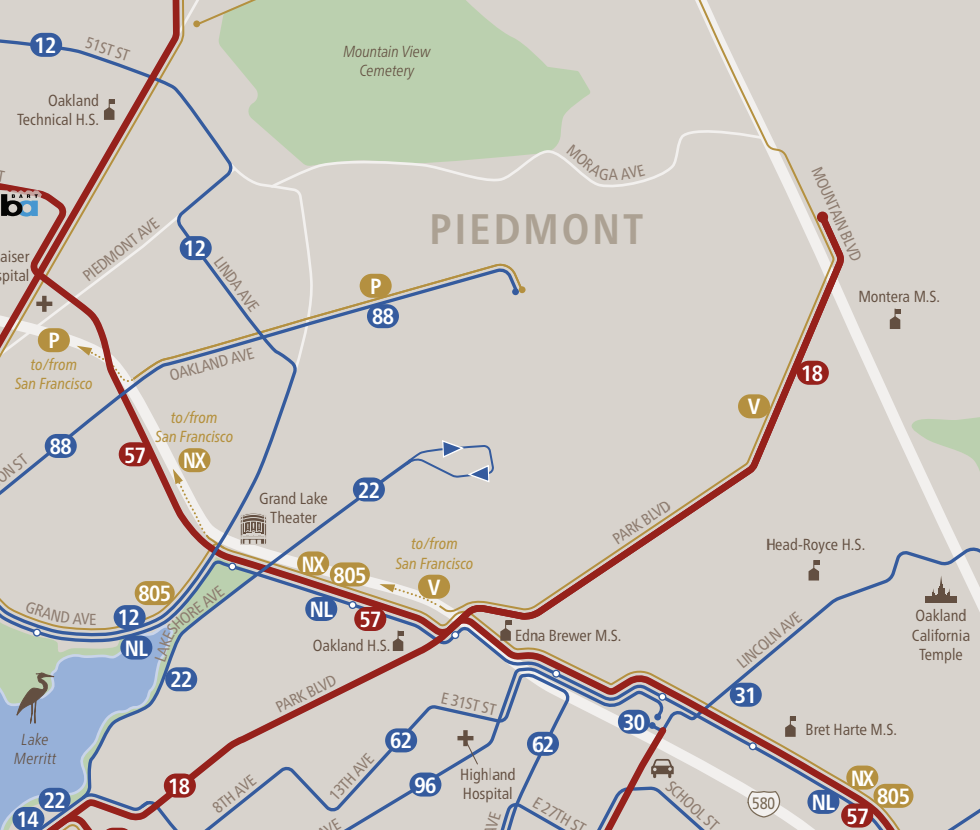

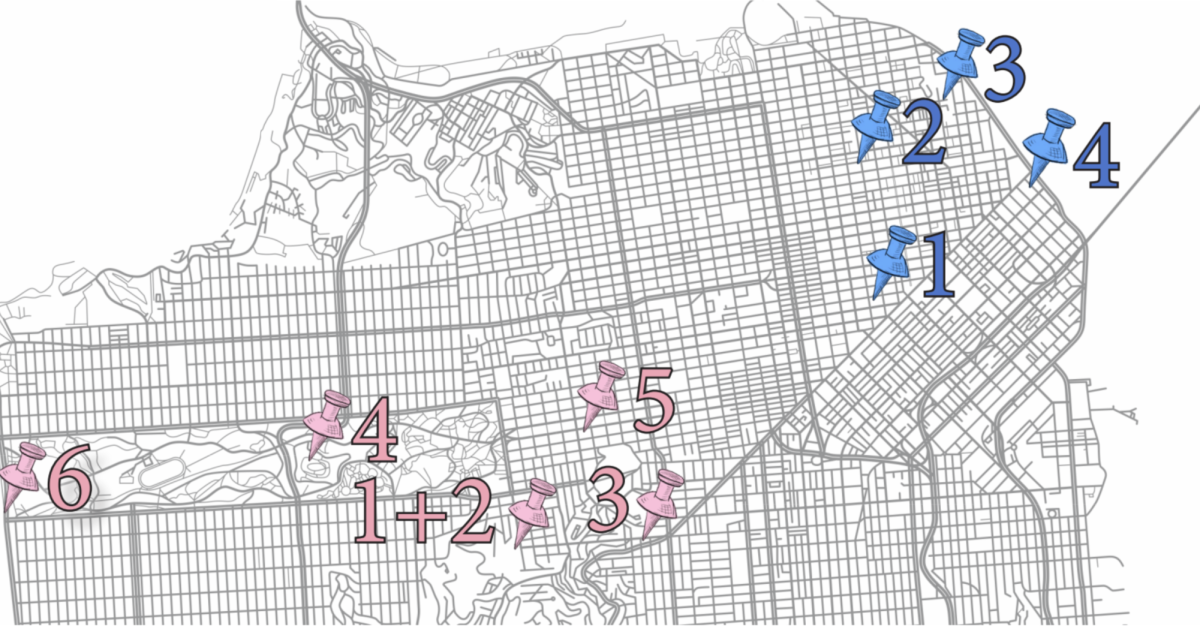

The current pace of book bannings and challenges hasn’t been seen since the Eighties, according to the New York Times. When a book is challenged, it means someone has asked for the text to be removed from shelves and classroom curriculums because they found it offensive or harmful to those who might access it. In Piedmont, nearly every book in the English program has been banned or challenged nationally at some point in time.

For example, Maus, by Art Spiegleman, is banned in a Tennessee county, while Piedmont students usually read it freshman year. The graphic novel was voted out of that county’s curriculum because of curse words and a drawing of a naked mouse. It’s a story about the Holocaust, making it likely to be challenged.

“Most of the challenges you’re getting now across the United States are because books have to do with subjects like LGBTQ+ rights, Civil Rights, African American rights, Jewish people, or the Holocaust. In general, people are like, ‘well, we don’t think this should be here because it makes people uncomfortable,’’ teacher-librarian Kathryn Levenson said. “Well, the best [books] in the world may not be comfortable.”

Levenson said she’s been approached once in her time at Piedmont with a book challenge. Nothing came of it, and the person who challenged the book had never even read the book itself.

English teacher Mercedes Foster has also been faced with a challenge once in her 18-year career. A parent argued that The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison shouldn’t be in Foster’s curriculum. The challenger’s reasoning was that it was inappropriate for students to have to read about topics that were so disturbing. The Bluest Eye covers topics like racism, child molestation, and incest.

“[The argument is that] ‘this is upsetting to students and so they shouldn’t have to face it in class,’ and it’s like, history is upsetting. Life can be upsetting and being able to explore [those complex ideas], in the safety of a classroom, with an adult makes you more prepared for actually going out there and doing stuff on your own,” Foster said. “The idea of just protecting students from anything that would [make them] feel sad or bad or afraid and then [throwing them] out into the world is wrong. I mean, is there any greater penalty than that?”

Foster also said that banning or censoring certain materials and books from classrooms is harmful to students.

“[When a book is] being banned, it gets a lot of attention. So there’s that one little ironic explosion of attention that the book gets,” she said. “But if it’s been taken out of the curriculum, five years later, those kids don’t want to get into trouble, and they just don’t have access to it anymore.”

Across the country, history lessons are being censored as well.

In Texas, there is a push to limit what public schools can teach about slavery and racism in history curriculums, according to the New York Times. Laws and resolutions that make teaching Critical Race Theory, which looks at how race and racism informs politics, law, and culture, illegal at school districts in 12 states have been recently passed.

“The laws all attempt, in some way, to tell teachers that they should be teaching a history that celebrates the accomplishments of the United States and doesn’t criticize or lay blame for racial oppression on any one particular group,” social studies teacher David Keller said. “The laws are kind of phrased a little bit in kind of a neutral way in the sense that they just say things like, ‘Teachers must teach history that doesn’t makes people feel ashamed of their racial heritage’.”

PUSD passed a resolution stating the district will focus on teaching a truthful version of the racial history of the US and will help students understand their own racial identities and the racial identities of those around them.

This year, Keller is working on bringing some change to the history curriculum. He said he wants to find more of a balance between teaching racial history in America.

Book bannings can come from any side of the political spectrum. Often, challenges from the left receive less backlash than those coming from the right.

Two lawmakers in New Jersey tried to have The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain, removed from New Jersey schools’ curriculums. Their argument was that removing this book would be an actively anti-racist act, as the novel uses racial slurs like the N-word consistently.

TsIn different areas, material is being challenged for different reasons. Students across America are getting different educations because of the political beliefs of their surrounding communities.