The Piedmont Police Department (PPD) received a $390,000 grant to implement a school resource officer (SRO) for the PHS, MHS, and PMS campuses. The grant would last for two and a half years, and would begin part-way into the 2019-2020 school year. The Piedmont Board of Education and City Council will decide whether or not to implement the grant in March.

“An SRO is a police officer or law enforcement officer that has specialized training to supplement four roles in a school setting: law enforcement officer, counselor, social worker, and teacher,” superintendent Randall Booker said.

The grant is funded by California’s Prop 56, which increased taxes on tobacco products to fund local agencies to reduce the illegal sale of tobacco products to minors, according to the Office of the Attorney General (OAG) website.

While the grant is not limited to SROs, Chief of Police Jeremy Bowers applied for an SRO program specifically, so PUSD can only use the grant for an SRO, Booker said.

Bowers said that he applied for the grant on Oct. 5 and received notification that PPD was awarded the grant in November.

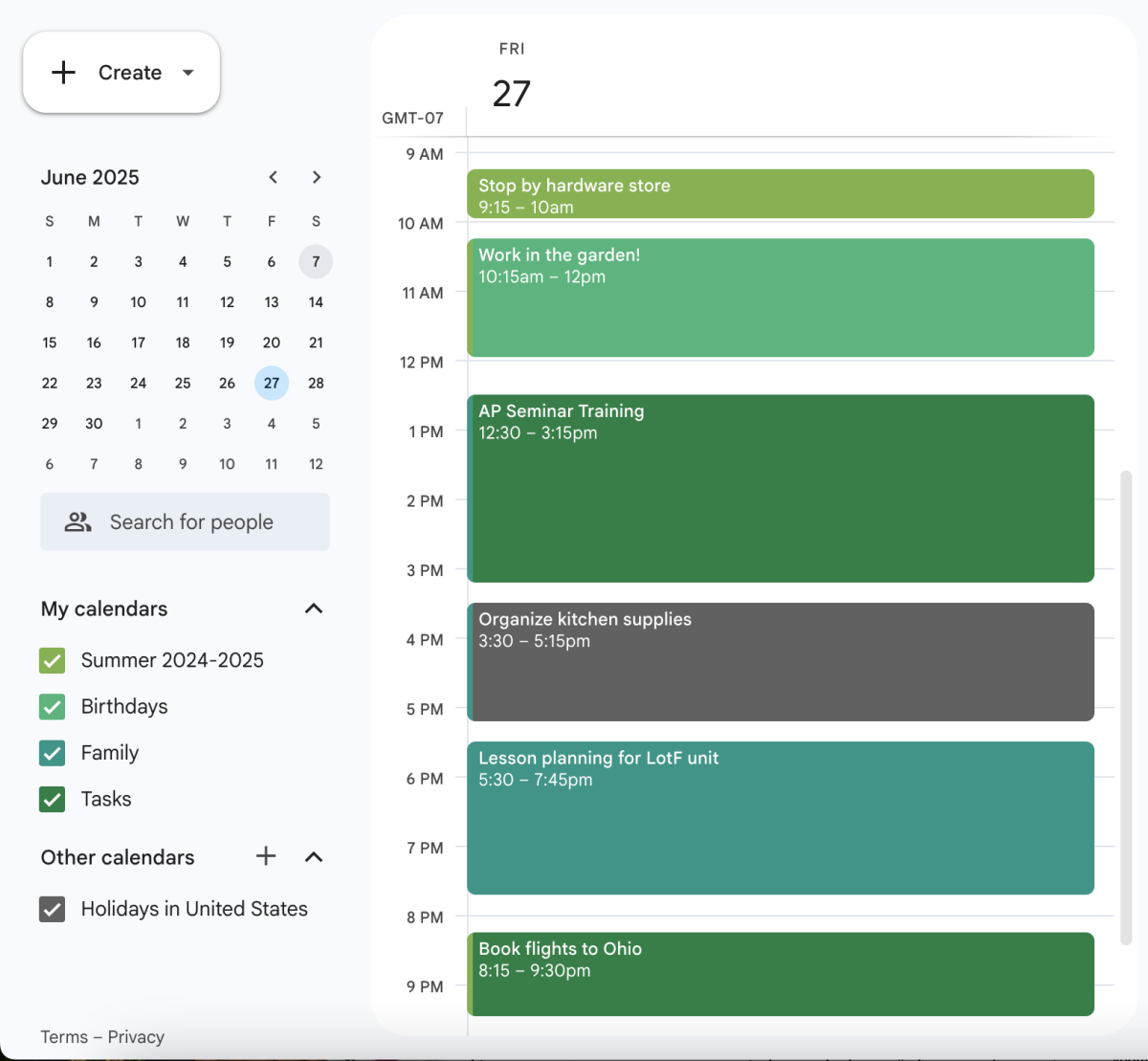

However, the Board of Education must pass the SRO proposal in order for it to move on to City Council. Both councils require a simple majority vote of three out of five members to approve the program, Bowers said. The Board of Education will meet on Feb. 27 to discuss the SRO, but final decisions will most likely be made in March.

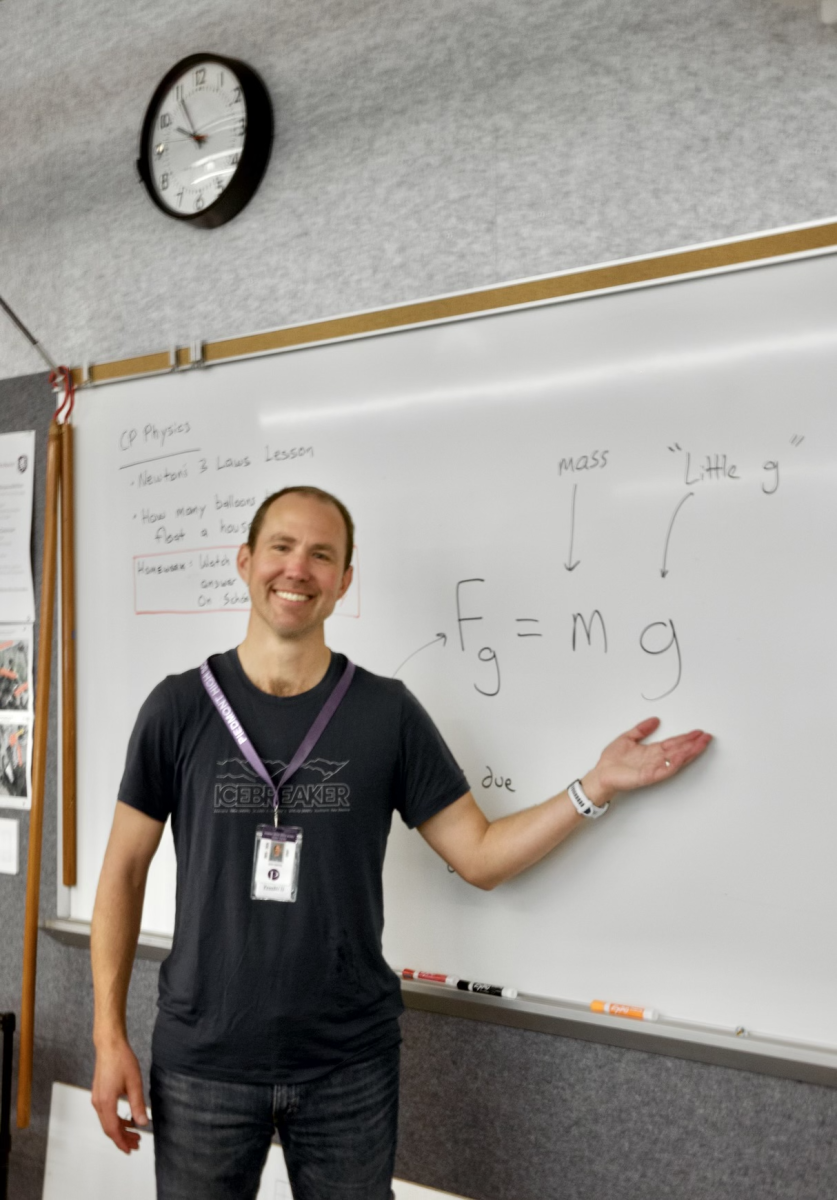

In California, SROs are required to go through 40 hours of additional training on top of their standard police officer training. The SRO training includes mentorship, adolescent psychology, de-escalation techniques, public speaking, and the functions of law enforcement within a school environment, according to the National Association of School Resource Officers.

“[Police officers] have to go through crisis intervention training, and implicit bias and racial profiling training are regulatory mandated,” Bowers said.

SROs can complete optional training in specialized courses such as peer support, restorative justice programs, and social media education. In some cases, the total training can amount to hundreds of hours, Bowers said. The training aims to ensure positive relationships between the SRO and students.

“I think that too many people are uncomfortable around police officers,” senior Jack Elvekrog said. “I think building relationships as a kid is a great way to put you in a good place moving forward in life.”

The SRO will also act as a resource for teachers, assistant principal Erin Pope said. Pope taught at Terra Linda High School for 15 years, where an SRO was present.

“In my experience, the SRO served as a really great resource for teachers in terms of educating us,” Pope said.

The officer can share their knowledge as a police officer with students and faculty, while simultaneously spreading the knowledge they gain as an SRO with other police officers. This allows their knowledge and skills to filter out across entire departments, Bowers said.

SROs can also go through substance abuse training. When applying for the grant, Bowers said he articulated Piedmont’s struggle with drug use and distribution on campus.

“A component of [the grant] has to be tobacco related,” Bowers said. “The vaping is clearly an issue at the schools.”

According to Piedmont’s 2018 California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS), 18 percent of freshmen, 38 percent of sophomores, 46 percent of juniors, 55 percent of seniors, and 41 percent of MHS students used alcohol or drugs in the 30 days prior to taking the survey.

“[Teachers] have pretty limited capacity to patrol student behavior on campus, particularly during class when most of the adults are working in their classrooms,” social studies teacher Gabrielle Kashani said.

Currently, Pope and campus supervisor Michael Bell monitor the student bathrooms, Pope said. If the SRO is hired, all three faculty members will monitor drug use, but Pope said she would remain in charge of discipline.

“The [SRO] would only get involved [with discipline] is if it was for something that we needed to call the police for anyway, like criminal behavior,” Pope said.

Booker said the SRO’s job is to augment services that PUSD already has.

“I see the SRO as a part of a greater team, a team of counselors, a team of teachers, a team of admin, one piece to the bigger puzzle,” Booker said.

Although protecting against an active shooter is an aspect of the SRO’s job, the prevalence of school shootings is not the main reason for hiring an SRO, Bowers said.

“I think people are smart enough to know the odds and statistics [of school shootings],” Bowers said. “But again, the world that I live in, in law enforcement, we have to prepare for unlikely events.”

An SRO will be more likely to arrive at and stop an incident before police officers because officers are not always in the police department building, Bowers said.

“Every second that we can knock down off of our response to that problem is a life saved, potentially,” Bowers said.

Bowers said he will not put a police officer on campus without a gun. It risks putting an SRO in a position where an incident could occur where they need a firearm but do not have one.

In addition, the budget plays a part in the City Council’s decision to implement the SRO because both the school district and the city are over budget, City Council member Jen Cavenaugh said.

“The numbers only get worse,” Cavenaugh said. “It’s not as if we foresee a lot of money coming in [in the future].”

The SRO will be paid $53,847 for the partial first year, $166,380 the second year, and $171,372 the third year, totalling $391,599 in salary and benefits for the first three years. PPD plans on absorbing the additional $1,599 cost not covered by the grant, as well as the cost of training into their budget, Bowers said.

“The amount of training that we would have this person go to would probably be around the area of $1,500 to $2,000,” Bowers said.

There is no solidified plan to maintain the cost of the SRO after the grant expires. The most likely scenario would result in a fifty-fifty split of funds by the city and the school district, Bowers said.

Bowers and Booker will present to the PMS Parent Club on Feb. 8 at 8:30 a.m., Booker said.

The Board of Education invites the community to share their opinion when they discuss the SRO on Feb. 27 at 7 p.m. at City Hall, Board of Education member Sarah Pearson said.

STUDENT OPINION:

According to a TPH poll taken by 183 PHS and MHS students, 17.5 percent of students think it is necessary for the SRO to carry a gun, 22.4 percent of students think that it might be necessary, and 60.1 percent of students do not think it is necessary.

According to the same poll, 21.9 percent of students feel more safe with an armed officer on campus, 29.5 percent of students feel no change, and 48.6 percent of students feel less safe.

There will be a subset of students, particularly students of color and students from other historically marginalized groups, who might feel threatened, frightened, or victimized if the program is not implemented correctly. The choice of the person hired for the SRO position plays the most critical role in the success of the program, said Wellness Center clinical supervisor and psychologist Alisa Crovetti.

“I think it needs to be a person who really comes at their job from a supportive and empathic stance,” Crovetti said. “For example, administration and staff need to be sensitive to how students might respond differently to an SRO who is a female of color versus a white male.”

Cavenaugh said that input from students of color plays a large role in her decision making process.

“When it comes to students of color and their lived experience on our campus, I have no idea what that’s like,” Cavenaugh said. “I’ve heard stories, but I go through life as a white woman.”

Currently, administration does not have a plan in place to help accommodate and communicate with students–specifically students of color–who have anxiety around the SRO, Booker said. Although he is unsure of the best way to alleviate the fears that students of color have, Booker said it begins with the interview process.

“Assuming the proposal gets approved, I think we need to have [MHS] students and [PHS] students on the interview committee,” Booker said. “I think part of it is just empowering students to participate in [choosing] who the person is going to be.”

MHS sophomore Ang Lee said that students should have a vote in the final decision making process.

“I think no matter how many titles and sparkles and ribbons you put over the title of ‘school resource officer,’ the thing that it boils down to is the fact that he’s going to have a loaded gun, and he’s going to be a police officer,” Lee said. “A lot of the kids at Millennium aren’t even comfortable with a police officer near them.”

Lee said many students still lack basic information about the SRO and should have been notified sooner.

Bowers and Booker expanded conversation about the SRO to students in January, speaking with PHS, MHS, and PMS ASB, as well as PHS Student Senate. Administration also sent out a survey seeking student input, Booker said.

“The overwhelming majority of the students based on what they know, what they’ve heard, or whatever it might be, are not in favor of [the SRO],” Booker said. “That doesn’t surprise me.”

If there is a student group that wants to talk about or learn about the SRO, Booker said he is happy to start a conversation with them.

“I don’t think we’re asking permission [from students],” Pope said. “But I do think it’s our responsibility to reduce anxiety around it and answer all of [students’] questions so they feel good about it. That way when the SRO arrives–or if the SRO arrives–it’s to a welcoming school community.”

Sophomore Athene Lajeunesse said she is one of many students who plan on attending the Feb. 27 Board of Education meeting to voice their concerns.

“I think it’s important to show the administration, [Board of Education], and City Council members how many people care about it, are against it, and how much we’re willing to go out of our way to communicate that,” Lajeunesse said.

Elvekrog said that the community can always reassesses the program after the grant expires to decide whether or not to continue it.

“I don’t think there’s any harm done that comes from that,” Elvekrog said. “I think that it’s a learning experience that has a lot of potential to be successful.”

While there may be benefits to an SRO program, clear data do not currently exist to support or dispute the effectiveness of SRO programs, Crovetti said.

“What we do have are data supporting the value of creating warm, welcoming, and inclusive school environments in reducing bullying and violence in schools,” Crovetti said. “Insofar as an SRO could really contribute to this, the program could be effective.”