To Drive or Not to Drive

Lanyards hang from pockets, jangling keys twirl around fingers.

“You want a ride? I got my license.”

Whether it be for sports, extracurriculars, or simply seeking a new experience, students duck into cars and race past their peers on foot–they’re free. For students, obtaining a driver’s license can be driven by freedom and necessity or blockaded by fear and needlessness.

“I can go hang out with people, go get food. Even just driving around, listening to music is a really fun experience,” senior Thorin Holmes said.

However, not all students were eager to obtain their licenses.

Junior Danielle Zaroukin has not begun the driving process. Zaroukin says that while she wants to get her license, stresses related to school and other obligations have pushed driving out of her priorities.

Being unable to drive, she often finds herself limited by means of transportation. Zaroukin must take the bus to get to school.

“It’s harder to get to far places easily,” Zaroukin said.

Zaroukin feels anxious about the prospect of learning to drive because of her concerns for safety.

“Hearing about accidents and how everything is so unsafe, it’s really scary to think about,” she said.

Senior Lucy Wheeler was in a collision soon after she obtained her license.

“When kids first get their license, they’re really kind of reckless until you have a big realization of how dangerous it really is,” Wheeler said.

With her experience, Wheeler encourages drivers to be careful on the road.

Other students have differing feelings from Zaroukin about driving, including sophomore Vivian Burke, who plans to get her license as soon as she’s eligible. Burke is confident in her driving capabilities and deems driving a necessity.

Burke lives outside of Piedmont, so she must be driven to school every day by her brother, a senior. However, since her brother is graduating this year, Burke wants to get her license soon so as to not rely on her parents for transportation.

Burke also recognizes the advantages of driving, including hanging out with friends from other schools and expanding her social circle.

Like Burke, Holmes needed to get his license when his older brother, whom he relied on for transportation, graduated.

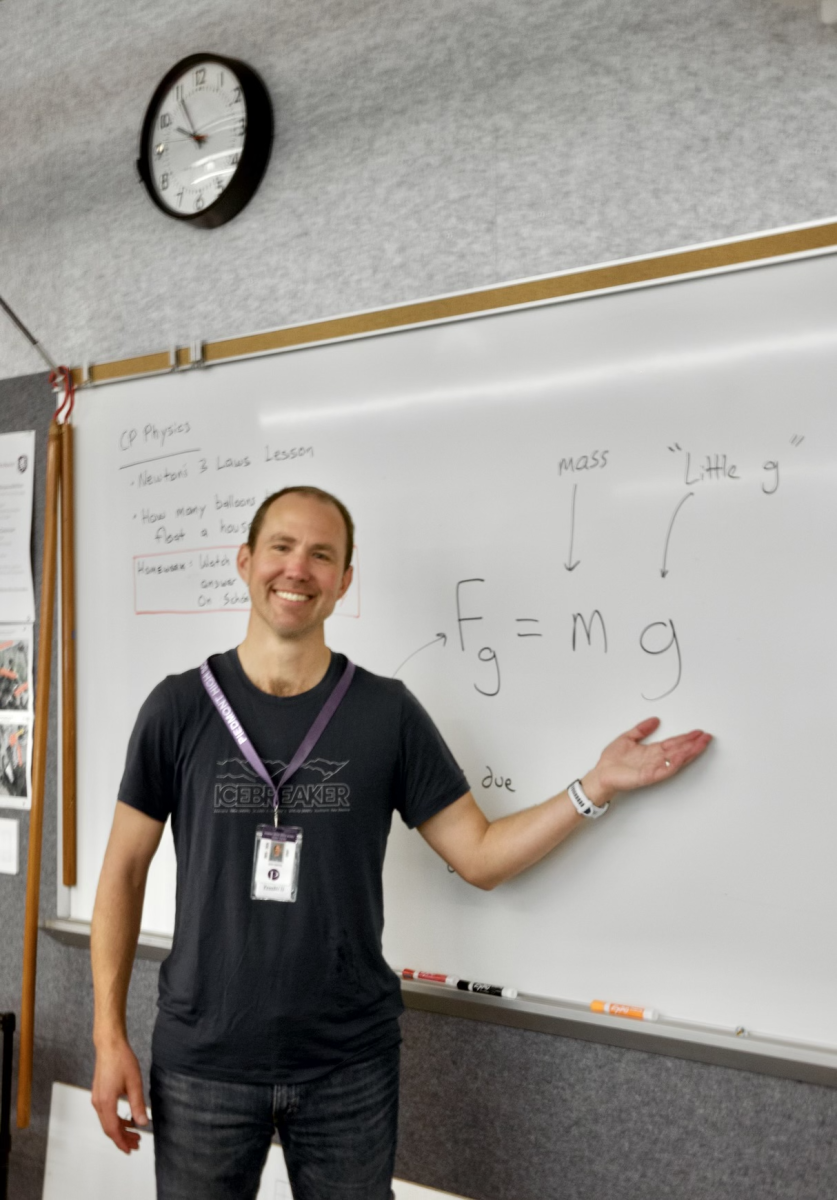

Holmes also highlighted Piedmont’s driving culture which differs from others. He contrasted drivers in rural California, whose destinations are barred by distance, to Piedmont student drivers in a city that is relatively walkable.

“[Rural community members] need their cars to get to school and the grocery store half an hour away,” Holmes said. “A lot of us can walk down to Piedmont Ave or Grand Ave and kind of get the things we need. So it’s more like a privilege rather than a necessity.”

Haylee Cheang, a junior who got her license just before school began, agreed that Piedmont’s drivers possess a privilege.

“A lot of people live close to school and don’t feel pressured or motivated to learn how to drive because they can walk,” Cheang said.

Cheang pointed out that Piedmont drivers’ experience also contrasts others because of students’ access to cars, as well as available funds for driver education, which Cheang acknowledges is expensive.

Junior Ellie Bleharski added to students’ unique privileges living in a small town, especially one of a tight-knit community.

“I think that people only really drive for the freedom,” Bleharski said.

Bleharski also mentioned residents’ relationship with law enforcement.

“Everyone knows each other. I know everyone’s driving past 11pm. People drive to and from parties when they’ve been drinking, and I feel like people just don’t worry about the driving laws since our community’s just such a bubble,” Bleharski said.

Junior Bruno Banuelos, also a newly licensed driver, acknowledged his responsibilities to safety and the law as a driver.

“It can be dangerous and you need to be very responsible, making sure that you’re always focused, and making sure that you’re always driving sober and off your phone,” he said.

Despite this responsibility, Banuelos recommends that students get their licenses when they are prepared.

“It’s given me the ability to go in the Bay Area wherever, whenever I want without having to rely on other people,” Banuelos said.

Drunk Driver or Designated Driver? A Tale of the Two Types

Danger. Disaster. Death.

The consequences are clear, but intoxicated driving remains a problem among Piedmont students.

“I’ve just done it so much that I feel like I’m fine and nothing’s going to happen,” senior Kelsey Rowland said.

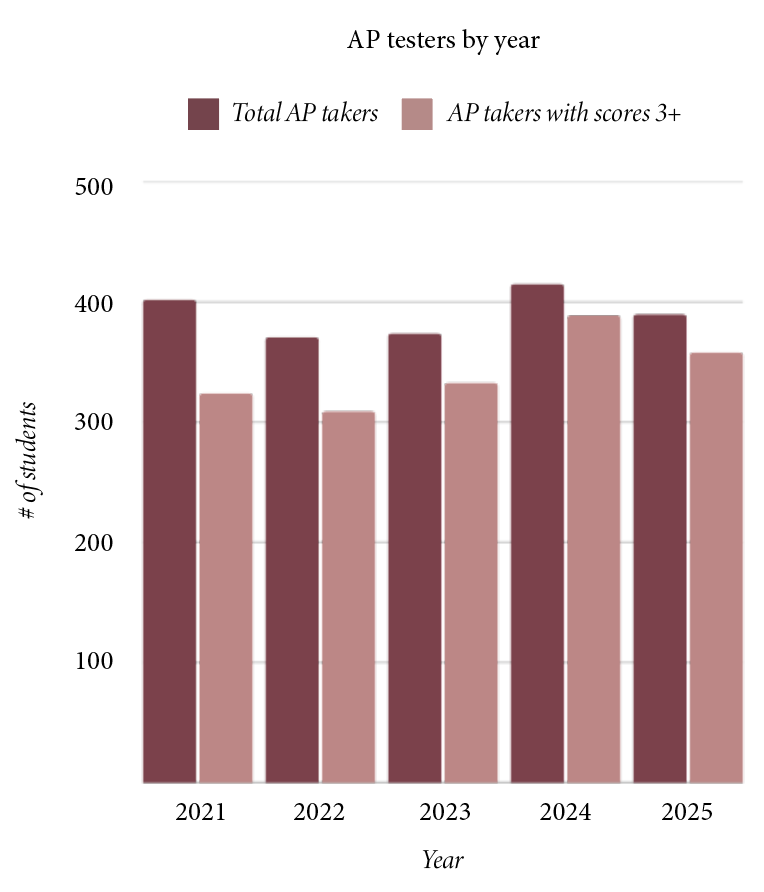

A Sept. 2023 TPH survey of 97 students showed that 19 percent had driven under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

“I think people are aware of the consequences [of intoxicated driving] but choose to ignore them for the sake of convenience,” junior Fredrick Larsson said.

Senior Justin Moore expanded on this idea of convenience.

“If you drive somewhere, it’s a pain to leave your car there. It’s quicker [to drive home] and it doesn’t cost as much money as an Uber,” senior Justin Moore said.

Three percent of people surveyed said they drive under the influence regularly.

“I live far away so I usually have to drive myself. If I want to play a [drinking] game with someone, I have to drink,” Rowland said. “[If it’s] only three sips of beer, it’s not going to do anything to me. It’s fine.”

Rowland said the only time she’s encountered law enforcement while driving intoxicated, they were somewhat understanding.

“I had a bunch of people in my car that I needed to get home. A cop came up to us and asked me if I was under the influence and I told him I had had one drink. He made someone else who was sober in the car get in the driver’s seat and drive us home,” Rowland said.

She said the person who took her place had also been drinking that night.

Piedmont Police Officer Hugo Diaz does not condone underage drinking or drug use in any way, but he encourages making a plan for getting home before going out to protect the safety of everyone involved.

“Whether you’re a minor or a senior citizen, if you’re driving under the influence, we are concerned for everyone’s safety,” Diaz said.

Senior Allison Jacobs has also driven under the influence.

She said she had driven to a friend’s party and anticipated sleeping over, but after police officers arrived to break up the party, she was forced to leave the house. Though she knew she was not in a good state to be driving, others accompanying her didn’t seem to mind; they wanted to be taken home.

“We were driving and I was really focused. The world was spinning and I had no sense of the dimensions of the car. It was really bad,” Jacobs said.

Forty-six percent of students surveyed by TPH said they had been in a car with an intoxicated driver.

“Sometimes you need to trust someone [to drive] because how else are you going to get out of that [kind of] situation?” junior Layla Finn said.

The concept of the “designated driver,” a person designated to abstain from drinking or using drugs in order to drive others home safely, is commonly employed among students, with fifty-seven percent of students surveyed by TPH having been a designated driver before. The Harvard School of Public Safety addressed the “designated driver” campaign of the late 1980s as one of the most successful for preventing intoxicated driving in the United States.

Larsson said the experience of being a designated driver was “a little odd”. He said it can be strange to not participate with everyone else and be the only one responsible for people’s safety. In addition to the burden of that responsibility, he said that being a designated driver can sometimes lead to feeling “left out” of the activity.

Diaz notes that a culture of acceptance and respect for this difficult responsibility is important for the safety of everyone who chooses the designated driver strategy.

“I kind of enjoy [being a designated driver]. I get everyone home safe and it feels nice. I don’t really care [about missing out]. I kind of like being sober,” Rowland said.

Despite this concept’s popularity, it has not been able to solve the issue of intoxicated driving in Piedmont completely. Rowland still drives herself home while intoxicated once a month.

Diaz said that when dealing with intoxicated drivers, the necessity of medical attention will always be a police officer’s first priority, but the process of being pulled over for a suspected DUI varies depending on the situation.

The officers will ask questions, and possibly utilize a breathalyzer, a device that detects the concentration of alcohol in a person’s blood through their breath. Police officers are also trained in Standardized Field Sobriety Tests, which can test someone’s ability to multitask or even focus their eyes.

“You go with what you see, what you’re getting, [and] what you’re being told. If we think we have enough to show that you’ve been driving intoxicated, we can get a warrant for your blood or breath sample, and you have to provide it or else you’re violating a court order,” Diaz said.

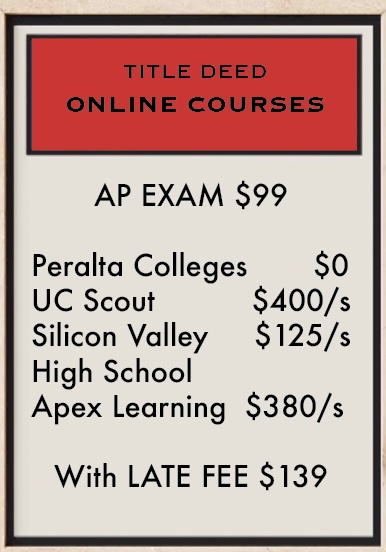

Drivers younger than 18 convicted of driving under the influence (DUI) will lose their driver’s license for a full year, or until they turn 18, whichever is a longer duration.

In addition to fines, they will have to pay for a three to nine-month DUI education course and double or triple the regular cost of car insurance. A DUI can be compounded with other charges, like underage drinking or drug use, and those charges will go on the driver’s permanent record.

“There are so many non-official social aspects that put you in different boxes; nobody will want to hire you,” Diaz said.

Despite these consequences, intoxicated driving continues in Piedmont.

“If we could predict drunk driving, it wouldn’t happen,” Diaz said.

He is enthusiastic about beginning a conversation with Piedmont students to move in a positive direction.

“I think [education is] the biggest thing. These are the risks, now assess them for yourself. Don’t just avoid [driving under the influence] because some adult told you not to. It’s in your best interest and [you should] understand why. I think it would be worthwhile starting a conversation like that,” he said.

The Ups and Downs of Car Ownership

From large house parties to social cliques, the American high school experience has been characterized by pop culture for years. One pillar of this idealistic experience is owning a car. In reality, though, owning a car is more of an icon of aspiration, a way to escape the anxieties of being a teenager. Yet for others, owning a car adds weight to that ever present blanket of anxiety.

“The act of getting out of [a negative] headspace by focusing on driving [and] listening to music can really take me away from whatever place I was in and whatever bad mood I was in,” said silver Toyota Camry owner Adia Lee.

For some students, just the thought that they have their own, and therefore autonomy, is freeing.

“I would just get up right now and walk outside my house, get into my car and go somewhere. I don’t even have to, but the idea that I could is so nice,” said driving permit owner and junior Mary Schickendanz said.

In a Sept. TPH survey of 97 students, 77.3 percent of students reported that they share their car.

Junior Cash Elmquist is one of these students, who shares a car with his brother, senior Ben Elmquist.

“[Although I share a car], I think [having my license] still gives me independence,” Elmquist said. “It’s definitely tough [sharing the car]. I think that it’s more tough for [Ben] because he’s had the car for two years now.”

“My mom told me [that driving] is a big responsibility. I shouldn’t take it for granted,” Elmquist said.

In fact, 87.7 percent of students reported that having their license has given them more responsibilities.

“When I’m driving [my] friends [I think about how] their lives are in my hands. I’m [also] careful with my life,” Lee said.

Senior Ceci Defazio also owns a car.

“I have to be home by 11:30 p.m., and that’s if I want to drive. If I can get someone else to drive me, I can be home by 12 a.m.,” said Defazio.

Defazio recently moved from Piedmont to Orinda. When she lived in Piedmont, her dad’s curfew for her was 12 a.m. Now that Defazio lives in Orinda and crosses the freeway to get home, her curfew is 11:30 p.m. Defazio said her dad is worried that if her car were to break down on the freeway, someone might pull over and harm her.

Car owner senior Cairo Osman said he has a lot of responsibilities that come with his car ownership.

“[I] pick up my sister from practice or pick up random stuff from my mom. I think it’s helpful for [my parents] to have an extra person,” said Osman.

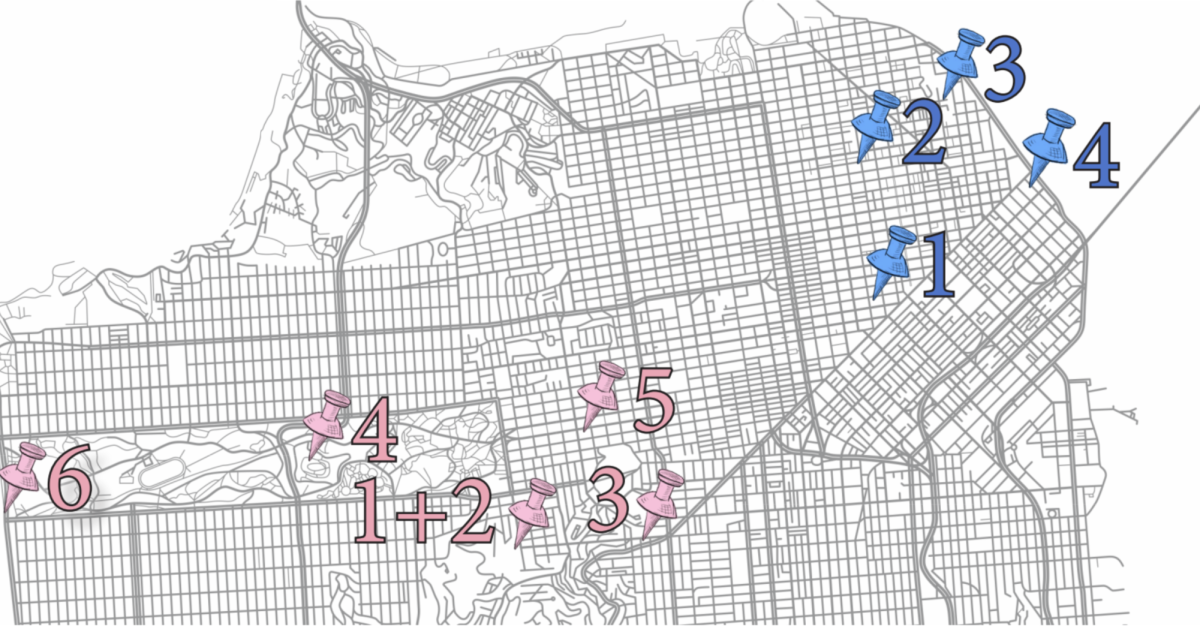

In addition to the new restrictions and responsibilities, driving is a huge financial burden. Defazio said jer car is a drives a “gas guzzler.” The money spent on gas from driving her friends to different outings– from San Francisco to soccer games– began to add up.

“I had to get a job [just]to support my gas [cost],” Defazio said.

In Piedmont, 64.2 percent of students report paying for car expenses in some way. Yet 54.6 percent of students are only a “little bit” or not at all aware of what their insurance is based on.

According to NerdWallet, a company that works to educate their clients to make the right financial decisions, the factors car insurers look at are gender, geographic location, marital status, driving record, and credit score. In addition to these factors, insurers look at the car being driven, the make and model of the car, the total miles driven, theft rates and safety features.

However, according to the California Department of Insurance, in 2019 in California, Commissioner Dave Jones prohibited gender from impacting car insurance rates.

In the TPH survey, 47.1 percent of students report illegally driving other students before they have had their license for a full year.

Parent of two teenagers at the high school, Shari Fujii said, “[If a teenager is illegally driving others and] somebody is seriously injured or killed, the other party –or even the family of the friend that your child is driving– can sue you.“

Fujii shared that adding two teenagers to their insurance plan tripled the cost of their insurance.