Disordered Eating

“I forgot to eat breakfast.”

“I forgot to eat lunch.”

“All I’ve had today is an iced coffee.”

Whether it be on walks to school with neighbors, in hallways with friends, or in classrooms with peers, students casually and frequently drop remarks on their eating habits.

Senior Elsa Rivera said that Piedmont has a prevalent culture regarding unhealthy eating habits and conversations around food.

“It’s everywhere. [The comments are] extremely unhealthy and really triggering,” Rivera said.

To her, it seemed that people almost bragged about not eating. She said that eating disorders can be very competitive, and this type of dialogue contributes to a comparative mindset.

“It starts to rub off on you and you’re like, ‘Well, if that person can do it, why can’t I?’ Like if really thin people are doing this, therefore that must be the secret to being thin. Because in Piedmont, and I think [with] teenage girls everywhere, they just want to be thin,” she said.

Junior Marty Fletcher views Piedmont’s culture towards disordered eating as lacking in supportive conversation.

“I feel like eating disorders [and] all types of self harm tend to be more shunned because you’re doing it to yourself. There’s not as much attention as there is on other issues,” Fletcher said. “Piedmont could do a better job on that and also [on embracing] a wider definition of beauty.”

Alisa Crovetti, Clinical Supervisor and Training Director at the Wellness Center, said that those struggling with eating disorders often have distinct personality styles.

“They have a temperament that allows them to be really good at being disciplined,” she said.

The mindset of this distinct group allows them to effectively restrict food intake.

“Someone would tell me that they were struggling and then I would be like, ‘I bet I can be sicker than you.’ It’s horrible,” Rivera said.

She said Piedmont’s culture along with seeing unrealistic standards online led to her struggles with eating. As a result of her disorder, she would often feel ill, have trouble standing, and feel cold. A significant loss of muscle also led to heart problems.

“I started to worry about my heart stopping, [and] I started to feel those symptoms of chest pain, [and heart] palpitations. That was the turning point, like, I don’t actually want to die,” she said.

Rivera and Fletcher both received professional therapy for their struggles.

Rivera said that though the therapists would warn her of the dangers of her disorder, it was ultimately up to her to begin properly fueling her body.

“[It was just] like, ‘I [don’t] need to know how many calories or macros or whatever are in this, I don’t care anymore. I just want to eat to feel healthy because I never want to feel that sick again,’” she said.

Except in very rare circumstances, Crovetti said that teenagers should never be losing weight.

Fletcher also described having a big fear of gaining weight and becoming fat. His unhealthy relationship with food then affected his relationships with others. During lunch, Fletcher would make up excuses for not eating with friends.

“I honestly think that people can be complacent on this issue and not realize that people close to them can be struggling. And it was just really, really hard to navigate how isolating it was,” he said. “It felt like a secret, it felt like a part of me, like a part of my identity.”

Being a male, Fletcher’s experience was even more isolating. He said he thinks that men’s experiences with eating disorders can be very dangerous because people don’t expect it. Crovetti said she thinks clinicians recognize it quickly, but agreed that there was a stereotype of white, upper-middle class women struggling with eating disorders.

As for friends of those struggling with disordered eating, Rivera said that in her experience, it’s better to speak up and ask if they’re okay. She said that for her, having friends sit and eat with her was also helpful.

“You don’t make it about the food, you just sit with them. And any food. Do not force people to eat healthy food, just get something that the person enjoys,” Rivera said.

For Rivera, that food was crepes and salmon.

For students struggling with disordered eating at Piedmont, Crovetti said that the Wellness Center is always available. If a student has serious physical health risks, therapists will work with kids and encourage them to reach out to their parents, and then connect families with pediatricians and other health specialists.

They can also help prevent a full blown eating disorder from developing.

“If students are finding that they’re overly focused on food intake and body image, this is a really good place to talk about that,” Crovetti said.

The impacts of disordered eating are not only felt immediately, but can also ultimately lead to death, as eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of any mental disorder, according to the South Carolina Department of Health.

“Restricting and losing as much weight as possible is a race to the bottom,” Fletcher said. “You’re not getting to [be a] better version of yourself, because you’re just depriving yourself of what you need to do any type of self improvement. So you’re not improving, you’re just hurting yourself in so many profound ways, psychologically and physically.”

Dissecting Gym Culture

Gymtimidation

Weights clang as the sound of grunts and the smell of sweat infiltrates the air. All around, gym-goers have their headphones jammed in, staring blankly into the mirrors between their sets. Their drained eyes, blank expressions, and swollen muscles are the only greeting for whoever walks through the gym doors.

First stepping into a gym can be very difficult. If a person is self-conscious about their body or inexperienced with working out, the intensity of the gym environment can be intimidating, according to the American Council on Exercise (ACE fitness). This fear of going to the gym is called “gymtimidation”.

“I used to be worried that I would be judged when I went to the gym. I was always really nervous to ask someone for a spot,” senior Ellis Moss said. Moss has been lifting for over a year now.

Sophomore Luck Peterson does bodybuilding style training and has gone to the gym six times a week for the past eight months. He said that the gym is a very intense, loud, and aggressive environment, so it can be overwhelming for someone without experience.

Insecurities surrounding body image can make a lifter feel like they will be judged by those who have more muscle.

“When I started I had that ‘skinny fat’ combo, so I was really self conscious,” Peterson said.

Gymtimidation can also stem from a lack of experience using proper form and lifting heavy weights. According to the YMCA, on average it takes a beginner eight weeks to see a noticeable change in muscle growth.

“When you see strong people it can be really intimidating because they might be looking at you thinking what you’re lifting is warmup weight,” senior Lucy Wheeler said. She has lifted every day for the past two years.

A product of this insecurity is ego lifting, or lifting too much weight, putting oneself in danger of injury, according to TS fitness, a personal training company.

“I started out ego lifting because the gym is such a scary place so you think that the more weight you lift, [the more] people will think you know what you’re doing,” Wheeler said.

But with increased experience and hours in the gym, the fear of judgment subsides.

“After about three months I sort of stopped caring,” Peterson said.

A lot of the stigmas people have about the gym that fuel gymtimidation are contradicted the more someone lifts.

“These intimidating preconceived notions people have about working out luckily are not true. The more you work out, the more you realize that everyone is just working on themselves, so if someone is judging you, it’s on them, not on you,” Moss said.

Toxic Masculinity

Man up! Get big! Be strong!

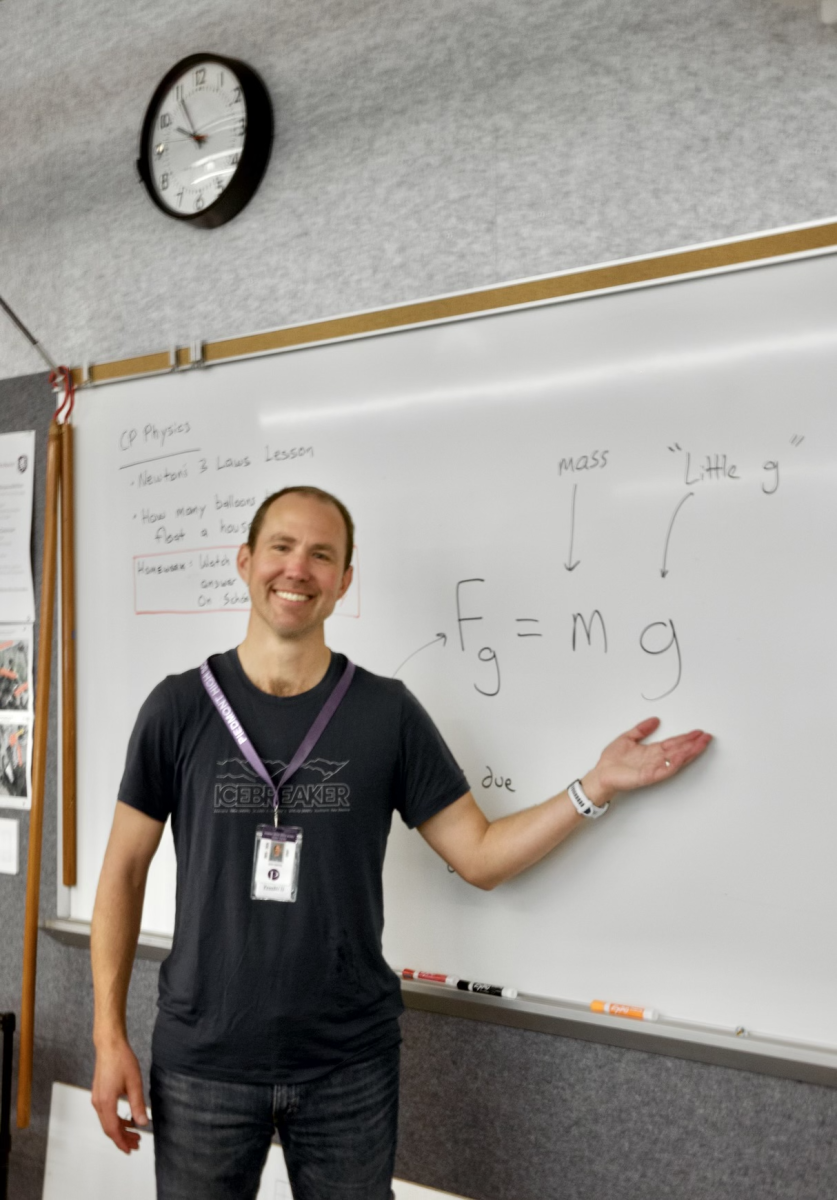

Lifting and athletics are used as an outlet for young men to express their emotions, because many are insecure about presenting emotional vulnerability, PHS English teacher Matthew Klein said. Klein has hosted weekly discussions about toxic masculinity during lunch for the past four years.

“For example, when you see tears come out of Stephen Curry’s eyes after winning a championship, people don’t call that un-masculine. It’s one of the only avenues where boys are allowed to feel the whole spectrum of emotions,” Klein said.

This suppression of emotions stems from the mix of both ridicule and encouragement that exist in male dominated workout spaces.

“People think belittling people is a good way to push them to be stronger but that’s not what a good partner does. It can lead to body image issues, especially with boys in regards to getting bigger and using performance enhancing drugs,” Klein said.

Many popular gyms such as the Oakland YMCA are male dominated and put external pressures on women who hope to participate in the space. According to the US Bureau of Labor statistics, 70.3% of people that weight train on a given day are men.

Wheeler said she has had to develop strategies to combat the stares of men at the YMCA.

Male workout groups are not the only part of the toxicity. Social media negatively affects the way men view their own masculinity Klein said.

“Boys are never taught directly what it means to be masculine. They look for things to teach them that and oftentimes the places where they learn them are very cartoonish views of masculinity where it’s simplified and very dumbed down,” Klein said.

Gym Routine

Monday: Push. Tuesday: Pull. Wednesday: Legs. Thursday: Push. Friday: Pull. Saturday: Legs. Sunday: Rest. Repeat.

For most lifters, going to the gym is a regimen, something they do several times a week.

“I’ve been lifting consistently for eight months, going six times a week,” Peterson said.

Most lifters go to the gym on consistent schedules, building it into their routines.

“I go home, take a nap, and then go to the gym at around 4:00,” Moss said.

Consistent gym-goers use splits, scheduling different lifts and movements that target specific muscle groups for different days of the week. With splits, lifters have a list of muscles and lifts that need to be targeted for each day.

“Monday is heavy leg day and then the next day is arms and back. I sort of switch off from there and then I often rest on Sundays,” Wheeler said.

Using these types of schedules helps lifters stay on a program and work out with direction.

“I go in with a plan everytime so my focus is where it needs to be,” Peterson said.

While this consistency is partially about building muscle optimally, many lifters consistently go to the gym because of its mental health benefits. According to the Mayo Clinic, exercise releases feel-good endorphins and helps distract people from their worries.

“[The gym] is a good place to focus on yourself and self improvement, while getting your mind off stuff,” Moss said.

Because of this, lifters channel the activity of lifting weights into a form of catharsis, working off stress.

“Mentally, I’d say I’m more balanced. If I’m having a horrible day at school, I can go to the gym and work it all off and be fine. That’s how I relieve my stress,” Wheeler said.

Diet

Counting carbs and tracking calories, students prepare their bodies to great lengths to increase athletic performance.

Jack Cramer said he works out for his mental well being, but recognizes that gym and sports culture can also have harmful effects.

“There’s definitely a fine line. It’s this really healthy thing, physically and mentally good for you. But at the same time, there’s body dysmorphia and obsession over hyper specific things,” Cramer said.

Changing nutrition is commonplace amongst athletes, influenced by the pressure of higher levels of play. Senior Natalia Martinez says she practices three times a week three times a week in preparation to play the sport in college. Martinez is currently committed to play for San Diego State’s Division One basketball program.

“I’ve been told that I wasn’t in shape and that totally messed with my mind. So I’ve had to change my diet a couple of times,” Martinez said.

A lack of knowledge around proper nutrition and pressures surrounding body image can lead student athletes into harmful mindsets or eating habits. Clubs like Mr. Olympia want to educate members on the eating habits that maximize muscle gain, said club co-founder and senior Logan Huh.

“I’m bulking right now and end towards January when lacrosse season starts, and I’ll start cutting then. That’s something we teach in the club because it is important if you want to grow muscle size or cut down to a slimmer size,” Huh said.

Bulk and cut cycles are the dietary method of alternating between periods of caloric surplus (bulking phase), and caloric restriction, according to Kyle T. Ganson, a professor at the University of Toronto, in a 2022 report for the National Library of Medicine.

However, cutting and bulking are not always healthy either. They have been directly linked to increased levels of muscle dysmorphia and eating disorders, according to a survey conducted by the Canadian Study of Adolescent Health Behaviors.

“I’m never going to do protein powder or creatine, I always try to avoid it, because I know it’s a slippery slope. Like the obsessive tracking calories thing, or ‘I need to get this amount of protein,’ ” Cramer said.

Athletes and people who exercise may need to eat 500 to 1000 calories a day more than the average person because of the extra energy they burn, according to Dr. Beth Oller, an editor of Familydoctor.org, a website provided by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Distorted Media

A finger scrolls across the screen as images of fit, clear-skinned models project their seemingly perfect lives on every platform. Phrases such as “Clean eating,” “Wellness” and “What I eat in a day” are tagged in every caption.

Whether it’s Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, or Pinterest, some form of social media is likely to be found on over 90 percent of all teenagers’ phones, according to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. A November TPH survey found that 94.2 percent of the 154 student respondents had at least one social media app downloaded onto their device.

Of these individuals who took the TPH survey, the majority feel that the time they have spent on such apps has led to more harm than good, with 60.7 percent of the students with social media stating that it has negatively influenced the way they view themselves.

“It definitely negatively affects me, because before I downloaded social media I didn’t know half of the insecurities that I have now existed,” junior Sabrina Carling said. “They were things that I never thought about before.”

Social media allows for users to manage their online identity, creating an unrealistic version of themselves by editing and applying filters to their pictures prior to posting them. Additionally, social media grants individuals the ability to select specific images, creating a “highlight reel” of their life, according to Psychology Today.

“When you’re on social media you’re seeing people at their best,” senior Sara Broach said. “You’re not always going to look your best, and look like those people do.”

Comparisons to these unreasonable standards are then encouraged through comments and interactions that communicate and emphasize societal expectations for how individuals should appear, according to Cambridge University Press.

“On social media everyone looks so perfect,” Carling said. “It’s a standard that nobody can reach, not even the girls posting that kind of stuff. That’s not their [real] life.”

According to Cambridge University Press, adolescents who derive self-esteem from their physical attractiveness are likely to take part in social comparison, evaluating their looks by comparing themselves to other social media users.

“I used to compare my life to other people’s, knowing it was fake most of the time,” said freshman Clara Shum.

Furthermore, engaging in such social appearance comparisons with other users’ photos on social media is associated with dissatisfaction in oneself, according to Cambridge University Press.

“If you only see people looking their best on their best days then it makes you feel like ‘Oh, if they look like this so often, why don’t I?’ ” junior Claire Warner said.

In the TPH survey, 26.9 percent of the 154 students with social media stated that they have felt influenced to photoshop or edit pictures of themselves in some way. Additionally, Warner feels that with the development of apps such as Facetune and Photoshop, combined with the multitude of filters present on social media apps, it has become increasingly difficult to detect whether or not an image is edited.

“It’s just close enough to you where it looks like you, but a better version,” Warner said.

Prior studies of adolescents have shown that editing one’s photos is associated with self-objectification. Self-objectification, as defined by Cambridge University Press, refers to individuals adopting an observer’s perspective of their own bodies. This can lead to anxiety over one’s physical appearance and body image concerns, among other effects.