“All means all.” The former Piedmont superintendent used to quote: “Everywhere, every time, every student. All means all.”

While fulfilling everyone’s needs in a classroom is very difficult, teachers adapt to make all students, including those who are neurodivergent, comfortable and successful in a learning environment.

English teacher Jamieson Mockel has substantial experience teaching neurodivergent students with neurotypes such as ADHD and Autism. To Mockel, giving students equal opportunities to learn is very important.

“We all learn differently, right? We all have different ways of looking at the world. The biggest challenge I’ve faced is making sure that my teaching style is diverse enough to where everybody in the room feels like they can catch on to some part of the lesson,” Mockel said.

Mockel teaches his classes in multiple ways, one of the strategies he uses being visual handouts.

“I don’t just speak out examples, sometimes I project them on the screen and give handouts and stuff for students who learn in a more tactile way, for more hands-on learners,” Mockel said.

Mockel has also found that it is important to change the way things are worded so they can be understood differently.

“I repeat myself a lot, and I say things in different ways, just because, for myself included, sometimes if somebody tells me something in one way, I don’t get it. But, you can switch it a little bit, and I go, ‘Oh, I understand it now,’” Mockel sayssaid.

History and ASB teacher Hayley Adams said she frequently provides “subtle”small accommodations all the time from class to class.

“I think accommodations are a lot more subtle than people know. Usually it’s just a reminder that someone needs a redirect. I’m just going to come over, I’m gonna laugh with them, and then get them back on track. That’s an accommodation I provide every day,” Adams said.

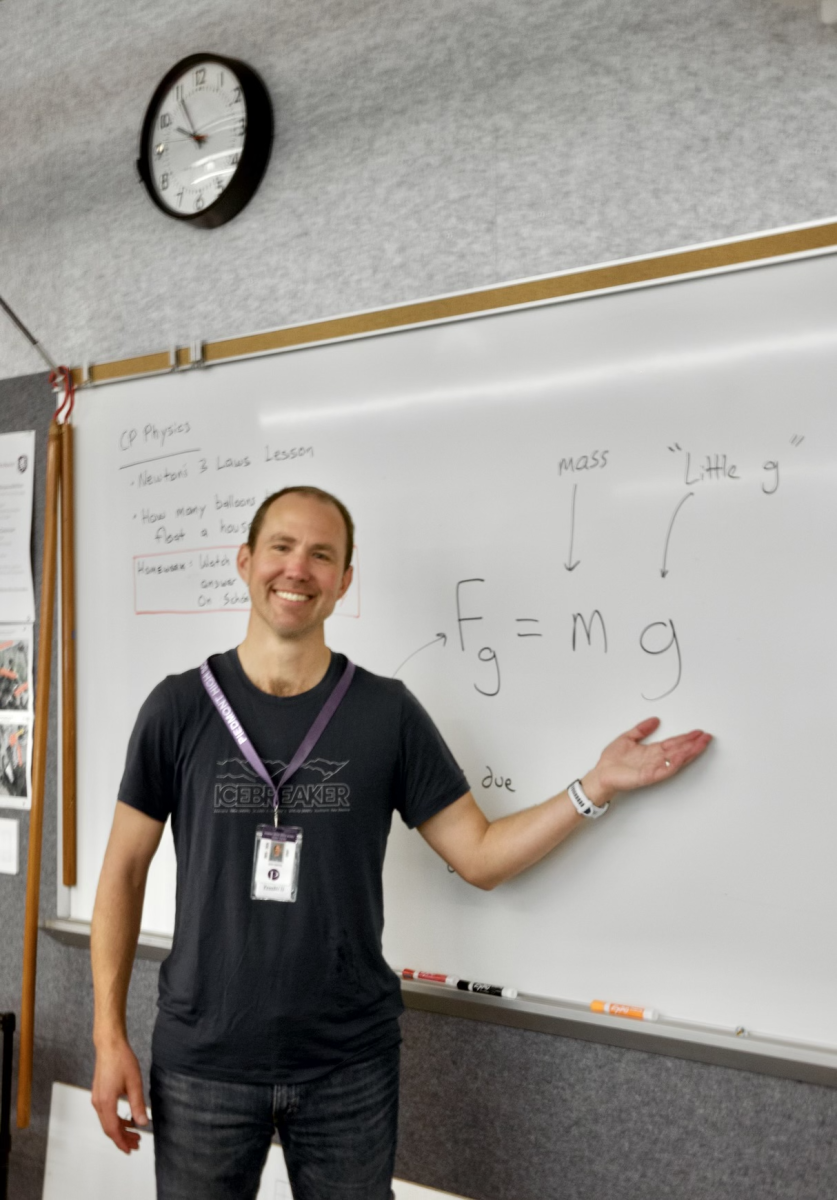

Math teacher Auban Willats also said she consistently works to figure out how to properly give accommodations when needed.

“One of the things that can be challenging is navigating extra time, which is an accommodation for students with a variety of neurodiversities,” Willats said. “That can be a challenge in math, where I don’t want you to have the test and then go away, review or study and then come back and do it later. That’s a trickiness to any kind of extended time situation.”

Willats said she’s found neurodivergent students tend to find math as more of a straightforward subject to learn compared to others.

“I think sometimes the struggle for, say, autistic students is they are more literal thinkers, and so metaphors and analogies are a little tricky,” Willats said. “But in math, there’s not too much of that.”

Adams recognizes that individualized support is necessary for students, but can be difficult to provide with such large class sizes.

“Everybody needs extra help. It’s the constraint of having 31 kids in the classroom and you have 12 kids who need something special from you, that can be really hard to balance,” Adams said.

Regardless of large class sizes, Adams tries to keep her classroom a safe space for neurodivergent students.

“At Piedmont, we have an issue with kids calling each other ‘sped,’ like the special education department. It’s an actual department, and it goes so beyond the realm of what kids fully know,” Adams said. “I don’t tolerate that.”

Adams believes in creating an inclusive environment for all students.

“I try really hard to have [neurodiverse students] be seen for their exceptionalities, but also see them just as I would anybody else,” said Adams.