Students are accustomed to patterns, symbols, and flags. Colored ribbons, Olympic rings, and peace signs are easily recognized as supporting various institutions and causes. However, students might still be discovering how a rainbow infinity sign connects to neurodiversity. Neurodiversity Club aims to bridge the gap in awareness, starting with displaying the symbol on a flag in the Alan Harvey Theater.

“We recognize that we have a lot of other groups represented, but we don’t have neurodiverse representation on campus as much as we’d like,” said specialized education teacher and Neurodiversity Club advisor Michelle Barbera.

“There is the stigma that people who have autism are just stupid, and that’s not the case,” said junior Alexander Chin, who started Neurodiversity Club after learning he is autistic.

Neurodiversity encompasses a broad range of different ways people think. Chin uses the analogy of a three-dimensional scatterplot to describe how people exhibit many distinct characteristics to varying degrees.

For example, sophomore and club member Callum Louch identifies as twice-exceptional, meaning he is highly capable in some skills while struggling with others.

Neurodiversity Club highlights lesser-known types of neurodivergence and how neurodivergent people contribute to society.

“Last year, we put up visuals about famous people, like Bill Gates who are neurodiverse. It was a way to start conversations,” Barbera said.

This year, the club is planning the first-ever school-wide presentation for Neurodiversity Week, March 17-23. Chin said the presentation is meant to help neurotypical students understand neurodivergent perspectives.

“I have seen so many times, even without realizing what they are doing, people just being so absurdly ableist,” said Louch.

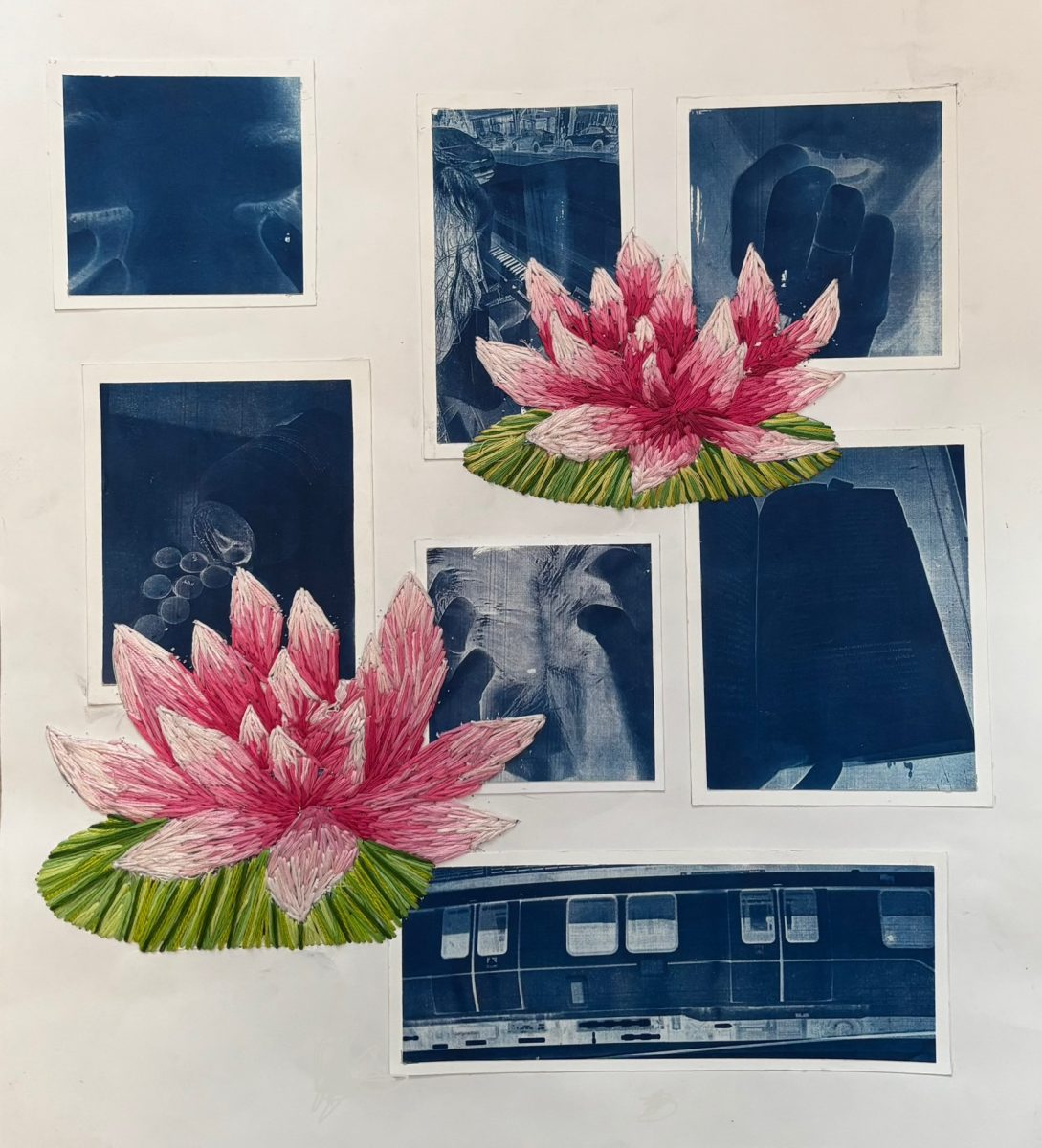

Neurodiversity Club assisted with the Advanced Acting class’ production of “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time” by providing pamphlets explaining neurodiversity and handing out stickers with the neurodiversity symbol.

The play follows 15-year-old Christopher Boone, giving the audience a look into his experiences and thought processes as an autistic adolescent.

Junior Collin Cameron, who played Boone, said he hopes the play puts the audience in Boone’s shoes.

Junior Abigail Cothran said she understood how Boone felt and related to some of his observations.

Cothran’s response was what the Advanced Acting class hoped to achieve with the play. By encouraging the audience to empathize with Boone, they aimed to increase neurodiversity awareness on campus.

“I think it really will add positive views, being able to see someone portrayed in such a positive way. The ending line of ‘I can do anything’ is a really powerful message,” junior Theodore Ferguson said.

Freshman Mara Pisani, who also saw the play, said she thinks it defies stereotypes about neurodivergent people, adding that Boone’s autism is portrayed as a strength at some points.

Defying stereotypes is a major step in creating a more inclusive environment. Because of this, Neurodiversity Club encourages neurotypical students to attend its weekly meetings on Mondays.

“Allyship is really important. It’s all about communication and listening,” Barbera said.

The club also creates a supportive environment for neurodivergent students to connect over shared experiences.

“It’s very helpful just as a space where we can talk about stuff rather than have to stay silent,” Louch said.

“It’s the little social bits like that which help me and the others in the club feel like they belong,” Chin said.

Neurodiversity Club also advocates to administrators for improvements to the school’s environment.

“As of last year, our goal is to put a neurodiversity flag on the flagpole. That would really show representation,” Barbera said.

Chin has also proposed changes, such as standardizing fonts to accommodate dyslexia, providing visual learning aids, and allowing sunglasses.

“Admin is really good about making sure that things are student-led, which is important,” Barbera said.

Another way they hope to improve the perception of neurodivergent students is by changing how they are described.

Barbera said the neurodivergent community tends to prefer identity-first descriptions instead of people-first ones. For example, one would say “autistic person” instead of “person with autism.”

“I suggested changing ‘special education’ to ‘specialized education’ to remove the negative connotations,” Chin said.

Paraprofessional Colleen Carroll-Browne said the education offered at Piedmont and Millennium High is truly specialized compared to other districts.

“The way we have structured our specialized education department is pretty comprehensive to meet the needs of a lot of students,” Carroll-Browne said.

Because of all the programs offered, Piedmont and Millennium High need funding, which the state of California only partially provides.

Carroll-Browne said parent campaigns and Piedmont Education Foundation cover much of the funds needed.

One parent campaign, Piedmonters for Inclusive Education, gives teachers grants to purchase supplemental materials and curricula for students with learning differences and advocates for how the district prioritizes its funding.

“We spent a lot of time last year on advocacy around the budget to make sure that special education resources, like funding for teachers, were protected in the budget,” said President of Piedmonters for Inclusive Education Sarah Karlinsky.

The group also advocates for improving the classroom experience for all students by using a set of guidelines called Universal Design for Learning.

“For example, having a visual schedule drawn out at the front of the classroom to let students know where they are in their day can help kids who are autistic, but it can also help kids who might be a little bit scrambled or have things that they need to work on for executive functioning,” Karlinsky said.

They also organize a free online and in-person speaker series about supporting neurodivergent students. Recent speakers discussed managing anxiety, learning with dyslexia, and improving decision-making.

Karlinsky said she hopes the speaker series helps teachers, families, and peers better support neurodivergent people around them.

Another way peers support each other is through the Affinity Mentorship program, where high school students mentor middle and elementary school students with similar backgrounds.

Former Affinity Mentor and senior Emma Eisemon worked with elementary school students with similar learning differences.

“I used to mentor an elementary school student who had autism and ADHD,” said Eisemon.

Despite age differences, mentors and mentees find common ground in their experiences.

“I formed a really close connection with my mentee. I felt like it was really beneficial to both of us to just talk about being differently abled,” Eisemon said.

The goal of Affinity Mentorship is for students to feel more comfortable and confident in their identity and how they interact with others.

“It’s not just being in the classroom. It’s also social, and for him, it was more getting that social interaction and figuring out how to interact with other kids,” Eisemon said.

She hopes her mentee feels more comfortable and confident in social interactions.

“What people don’t understand is that it doesn’t stop at classroom needs; it goes beyond that,” Eisemon said.