From the tech labs of Silicon Valley to the movie sets of Los Angeles, California has long stood as the world’s launchpad for innovation. This is the state where algorithms are engineered to change lives, where AI diagnoses disease, powers next-generation animation, and steers cars through traffic. Yet just miles from these breakthroughs, in classrooms from Silicon Valley to Los Angeles, students continue to be educated as if the AI revolution isn’t happening.

But that revolution is happening fast. AI is everywhere; it’s the invisible engine driving innovation, steering international relations, transforming healthcare, and accelerating scientific discoveries.

Over the past three years, AI has emerged as a key focus of global policy. At G7 summits, leaders have pledged to develop trustworthy AI that serves society, rather than threatening it. In the United States, the current administration has launched the “AI for American Innovation, Industry, Workers, and Values” agenda. In his first week back in office, President Trump signed an executive order focused on U.S. global AI dominance and unveiled “Stargate,” a $500 billion private-sector initiative aimed at building domestic AI infrastructure. A recent visit to the Middle East reinforced AI’s growing role in diplomacy and strategy, particularly in the lead-up to 2030. AI breakthroughs earned Nobel Prizes in physics and chemistry in 2024, and, according to the 2025 AI index, US AI investment hit $109.1 billion, nearly half of Europe’s and 12 times China’s. Business adoption surged from 55% to 78% in one year.

Yet amid all the talk of global dominance, we’re forgetting the first, and arguably most important, frontline: education. If the world is being redrawn by AI, who’s preparing the next generation to lead it? In California, the epicenter of global tech innovation, there is little evidence that public education is rising to the challenge.

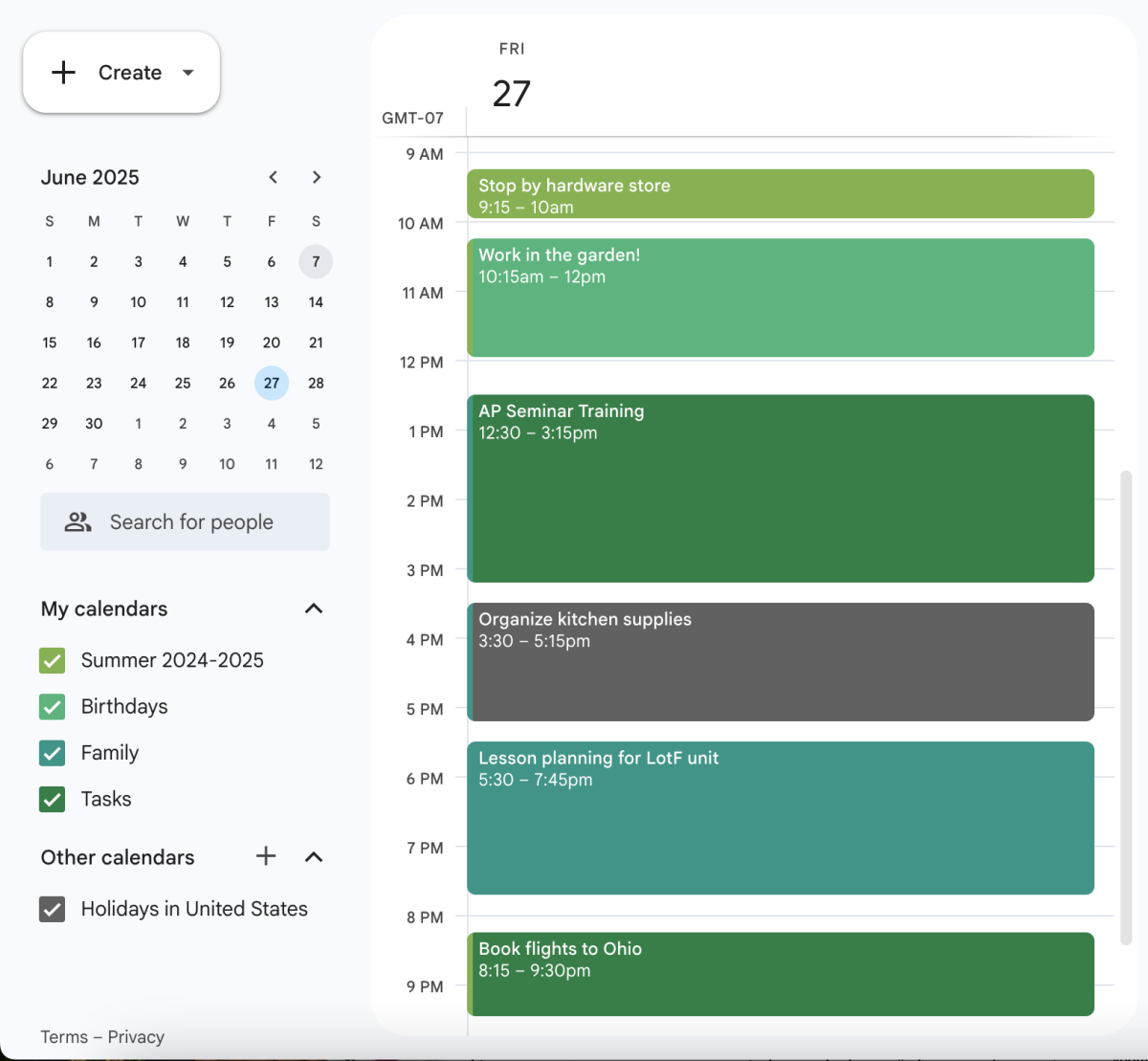

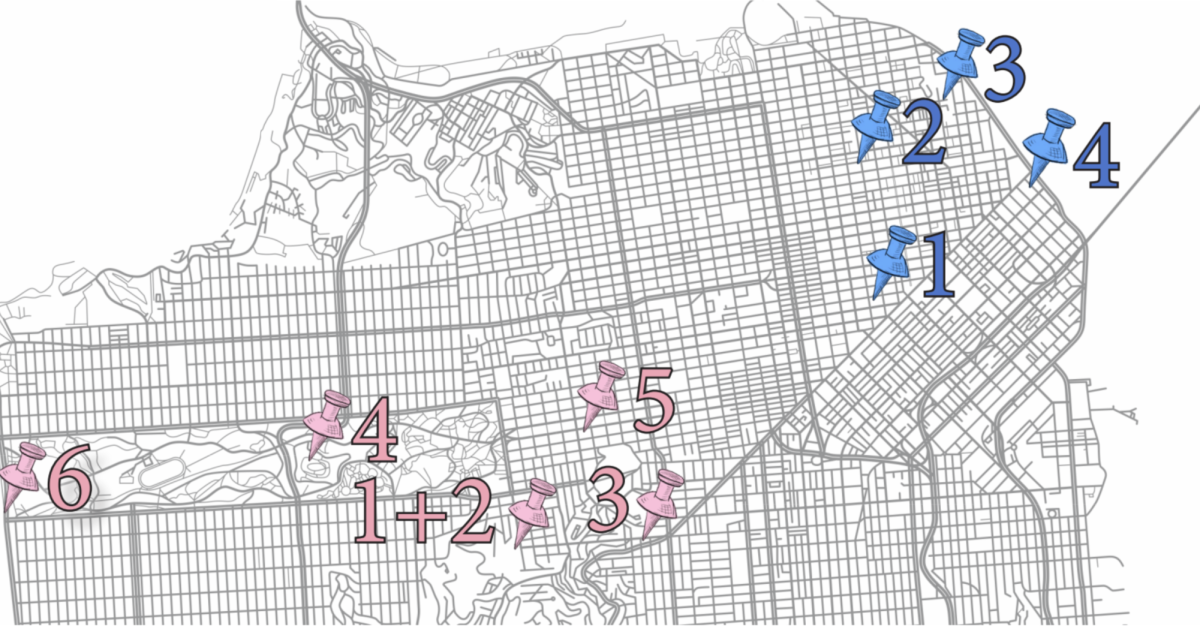

A new student-led survey paints a stark truth: the classrooms in today’s global cradle of innovation are stuck in a different era and oblivious to the very revolution their state is fueling. The survey was conducted across three well-resourced public high schools —Piedmont High School in the East Bay, Gunn High School in Palo Alto, and Palisades Charter High School in Los Angeles —and one of the country’s largest and most prestigious public universities, the University of California, Berkeley.

Whether in high school or at university, students paint a picture of classrooms untouched by the AI transformation happening all around them. These aren’t under-resourced schools; they are located in some of the wealthiest zip codes in California, boasting strong academic reputations and access to tech-savvy communities. If these schools are lagging behind, what hope is there for the rest?

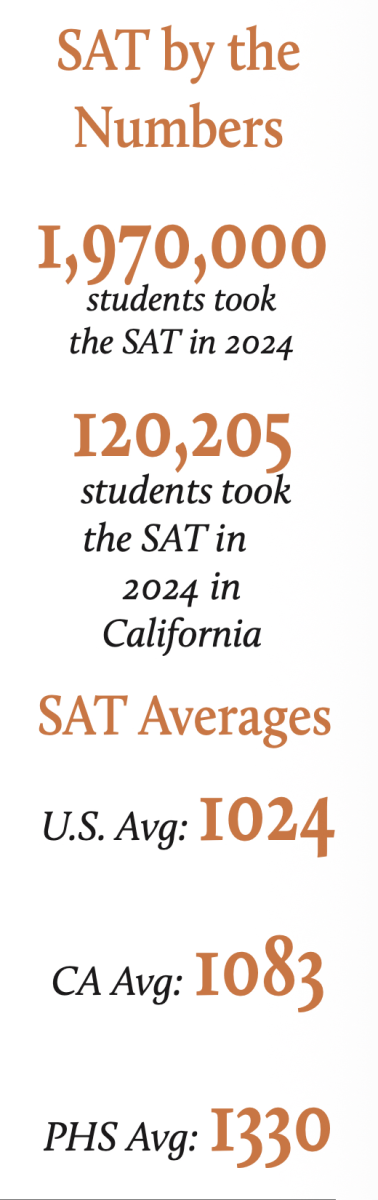

The data from these 764 students speaks volumes, with more than 80% of students across each one of these schools reporting only a basic to moderate grasp of AI. Even more concerning is that schools are doing very little to bridge that gap. A staggering 86.1% at Piedmont, 70.2% at Palisades, and 62.6% at Gunn reported that AI is either not taught or barely mentioned. When asked if their schools were preparing them for an AI future, 87.7% at Piedmont, 79.4% at Palisades, and 71.9% at Gunn said no. Indeed, when asked to assess their school’s preparation for the age of AI, only 6% of students across all schools reported feeling “well prepared.” At Piedmont, that number was zero.

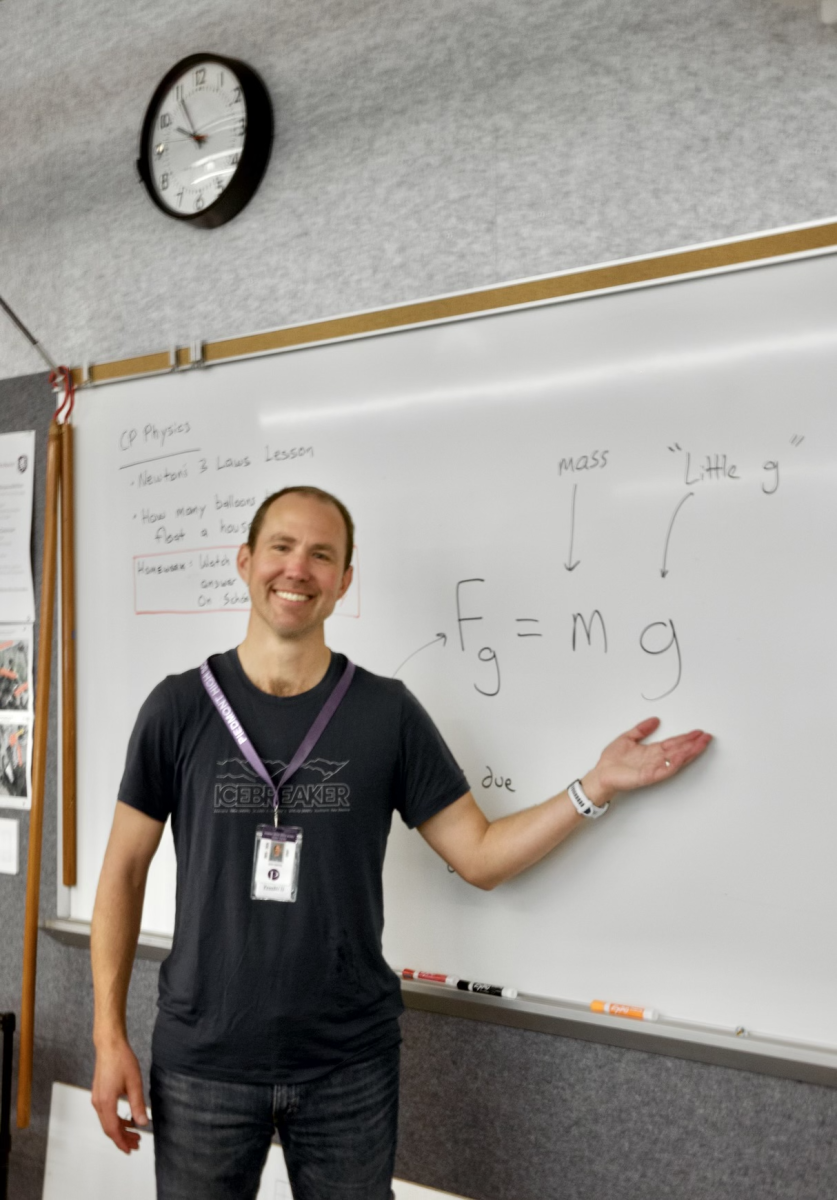

Teachers want to act but feel unprepared. While 81% of U.S. teachers agree that AI should be part of foundational learning, fewer than half feel ready to teach it. Students want to see changes, not just in how technology is integrated, but in how schools prepare them for a world where new jobs are emerging, new skills are essential, and the meaning of knowledge itself is shifting. Indeed, in this student-led survey, consistent across all three schools, a strong majority of the students (85.6%) support integration of AI in the classroom, with 67.8% supporting selective or strictly supervised use, reflecting concerns about fairness, academic integrity, and preserving distinctions in individual effort. The highest level of endorsement (almost 92%) came from UCB students.

This enthusiasm for AI in education is accompanied by a deeper understanding of what meaningful preparation must involve. One challenge is the kind of learning students perceive as essential: across all three high schools and UCB, over 70% prioritized human-centered skills (such as critical thinking, creativity, communication, emotional intelligence, and adaptability) over technical abilities like coding or data analysis. A second challenge is ensuring equitable access to these skills. Many worry that the uneven implementation of AI-enhanced learning could deepen existing educational disparities, with an average of 45% across the three schools believing that such shifts will only partially narrow the gap, or approximately 20% at Piedmont and Palisades, and 31.3% at Gunn, believing it may worsen the gap entirely.

A third, more immediate concern, as AI enters classrooms, is the lack of institutional readiness to help students navigate the risks, leaving them exposed to threats like manipulation, misinformation, and emotional exploitation. The consequences of this vacuum are already visible, revealing a frightening lack of awareness among students. At Piedmont, 87.3% of students, and similarly high numbers at Palisades (79.3%) and Gunn (71.9%), were unaware that AI is already deeply ingrained in newsfeed filters and may even influence decisions about friendships, quietly shaping how they think and communicate. At Gunn, where more students (40%) acknowledged emotional effects, such as decreased depth in friendships or growing discomfort with confrontation, there was still no indication that the school was helping students make sense of these changes.

The problem, of course, isn’t that California doesn’t know what’s coming. On September 29, 2024, Governor Gavin Newsom signed into law Assembly Bill 2876, requiring AI instruction in K–12 education. But in practice, the law lacks teeth. There is no defined curriculum, no dedicated funding, and no teacher training strategy. The message to schools seems to be: Figure it out, or don’t.

In contrast, other countries aren’t waiting. According to the International Business Times UK and Business Insider in China, students as young as 8 are being taught the fundamentals of AI. Estonia plans to provide all 16- and 17-year-olds with personalized AI accounts by 2027. In Germany, AI is now in nearly a third of schools and universities. France is deploying AI into its high school curriculum. The UK has launched a national AI campus. Even in the U.S., according to the Virginia Tech News, states like North Carolina and Virginia have pilot programs that teach AI as both a technical and social subject.

California, for all its innovation, is failing the very people who will inherit its technological legacy. Students here aren’t asking for a crash course in machine learning. They’re asking to understand the world they’re already living in. They want schools that prepare them not just to use technology, but to shape it.

If the nation’s innovation capital wants to remain worthy of that title, it needs to treat AI literacy not as a luxury but as a critical and urgent necessity. The question for California’s public schools is whether it will equip its students to shape the AI-driven world or merely adapt to it. The next generation isn’t waiting. They’re already asking the right questions. It’s time for the adults to catch up.