The beginning of each school year brings familiar frustrations: students stuck in unwanted periods, missing electives, and gaps in schedules. But behind these complaints lies a complex web of negotiations, union contracts, and algorithmic limitations which makes scheduling that satisfies every student nearly impossible.

PHS counselor Michelle Hoang said that this year’s scheduling challenges have been particularly pronounced in Periods two, six, and seven, with administrators struggling to balance teacher workloads, student needs, and district funding constraints.

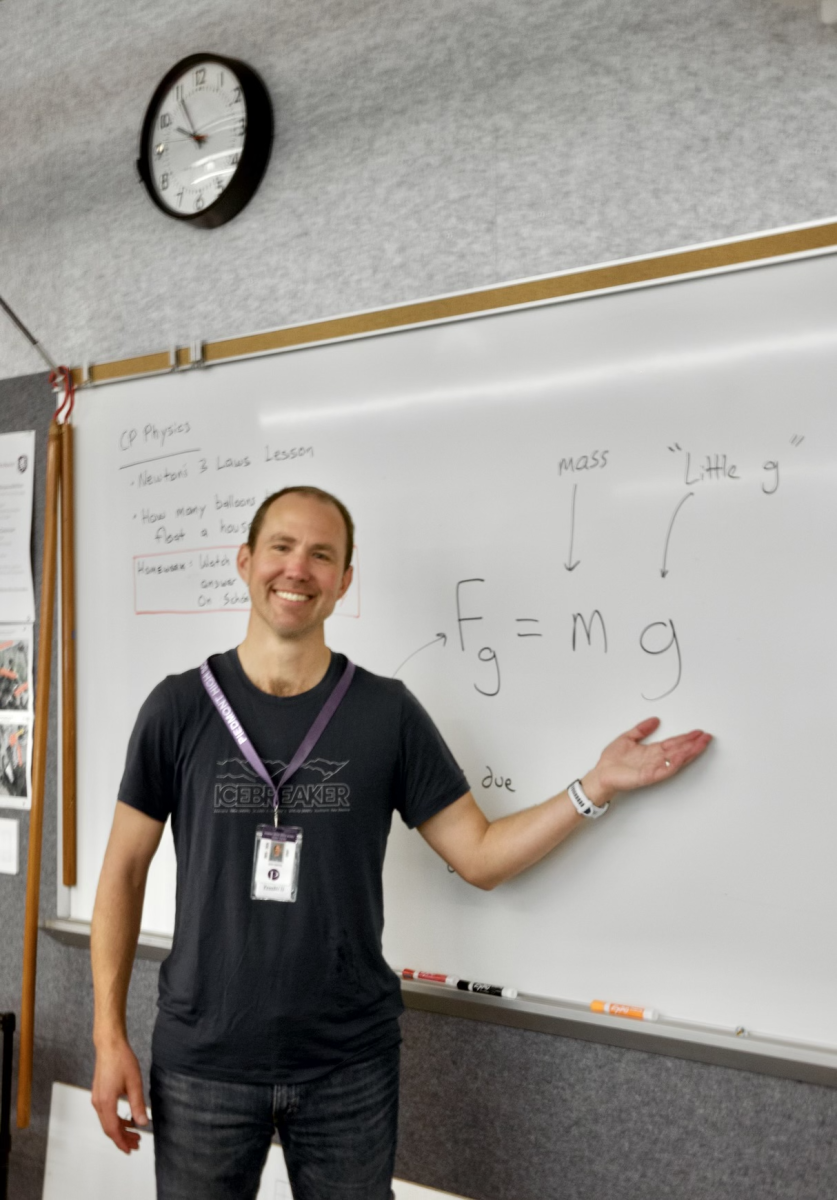

The shift from manual to automated scheduling has fundamentally changed how student schedules are created. “There used to be a big chart that the assistant principal would put on the wall with all the teachers and all the classes,” said English teacher Mercedes Foster. “They spent weeks doing it, tweaking it this way and that way, moving kids here and there. But most kids got what they wanted.”

While efficient, the current automated system has subtracted from the human ability to respond to individual needs.

“It does take the human element out of it,” Foster said. “Special accommodations are harder to implement. For example, situations like ‘my son can’t be in the same class with this kid because they’ve had issues’–that stuff doesn’t factor in.”

Foster has also noticed classes heavily skewed toward the first half of the alphabet, a pattern with lasting consequences for students.

“I’ll have mostly A’s and B’s in a class,” Foster said. “These kids are always stuck together in other classes, too.”

Figuring out scheduling begins months before students set foot in classrooms. Despite how straightforward it may appear to students, however, administrators deal with negotiations between the school and district over funding and teacher assignments.

Additionally, each teacher operates under Full Time Equivalent (FTE) contracts that dictate how many classes they can teach, with additional requirements for prep periods that must be factored into the master schedule

“Teachers need to have at least one prep period per day if they’re teaching 1.0,” Hoang said.

Foster said last year, the scheduling algorithm’s limits impacted her Creative Writing Class because 20 students signed up, but the class didn’t run due to “insufficient enrollment.” This year, 28 students initially enrolled, but scheduling conflicts reduced the actual class size to 17 .

“Forty-four people wanted creative writing, which is wonderful. There are 15 people in my class because the schedule didn’t work out,” Foster said. “People look at that and think, ‘Oh, nobody wants to be in creative writing.’ But that’s not true. It perpetuates a belief in the community that it’s not popular.”

The pattern repeats across subjects, creating a false narrative about student demand.

“The algorithm says the kids dropped it, so it’s less popular. No! It’s the scheduling!” Foster said.

These last-minute changes affect students directly.

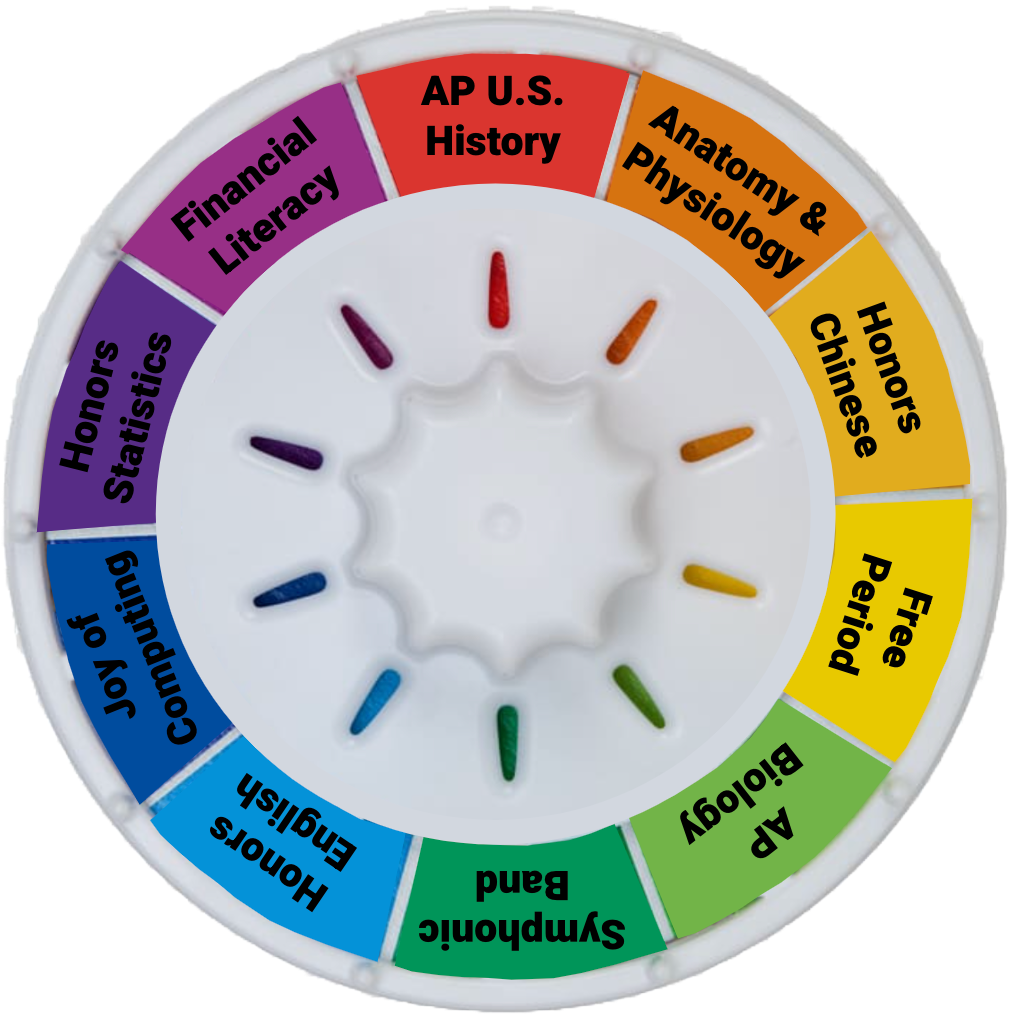

Senior Elias Reed-Miguel said he requested the electives Ethnic Studies and Law and Society but instead was given a free period. Reed-Miguel ultimately had to proactively request an elective that he wasn’t initially interested in, and ended up in Psychology.

The situation becomes more complex when students request unscheduled periods, which administrators now believe may be exacerbating scheduling problems. The school’s scheduling algorithm appears to struggle when too many students opt for free periods, creating cascading effects throughout the master schedule.

“Don’t sign up for unscheduled periods until you get your classes,” Hoang said as advice to future students. “If students had filled their classes instead and then dropped after they saw their classes, we would have likely been able to fill more schedules.”

Senior Ava Rivera said scheduling complications left her with an unscheduled fourth period that administrators refused to fill, despite her preference to avoid midday breaks.

“I asked my counselor, and she said a lot of people have already asked to switch specifically out of AP Lit and there’s no room,” Rivera said.

Looking forward, Hoang said that it’s crucial for students and teachers alike to understand how complex the scheduling process is, and that it’s nearly impossible to fully satisfy the wants of everyone on campus.

“Every year is its own kind of beast,” Hoang said. “Like, no one’s going to be happy. It’s just a matter of how many people are going to be unhappy.”