The difference between drinking in college and high school is more than just the difference between a row of eighteen beer pong tables in a fraternity and a converted dining room table in somebody’s house.

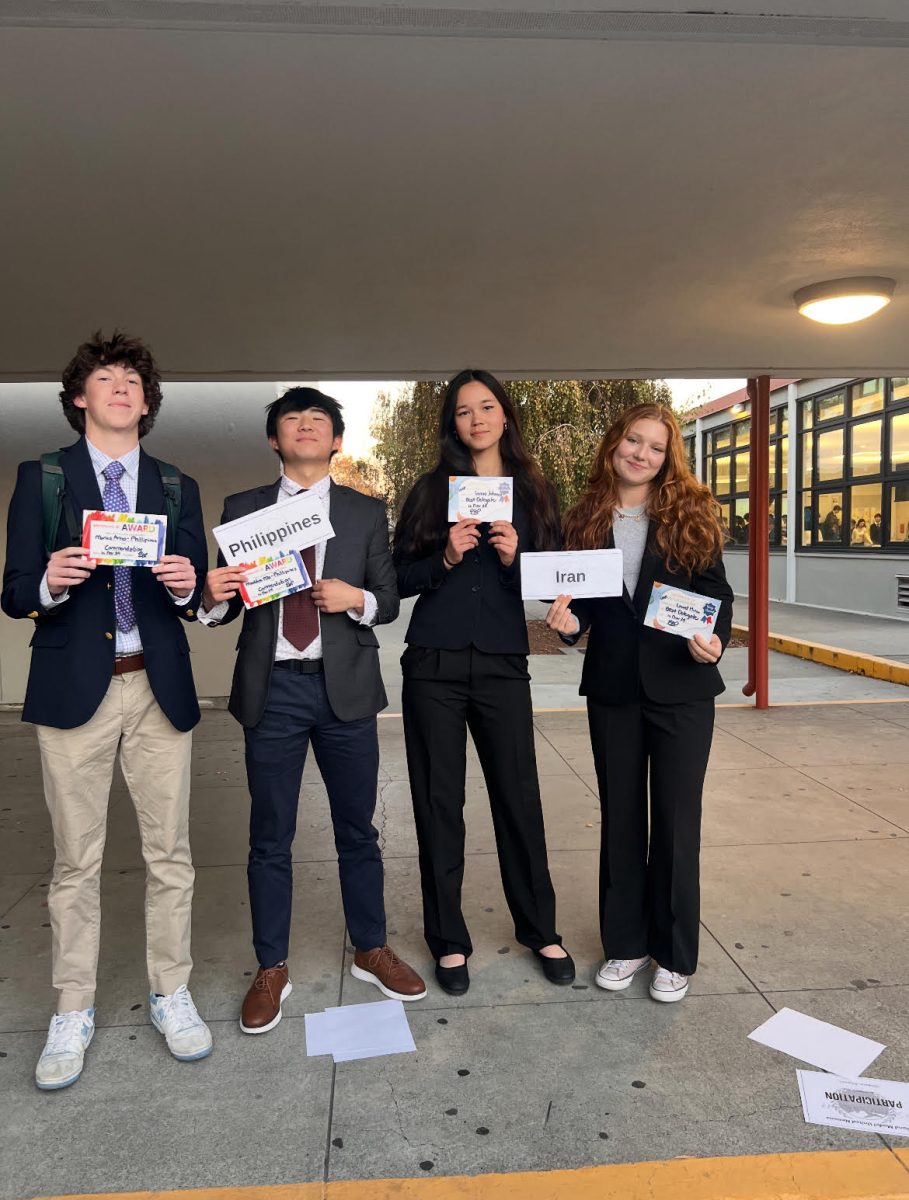

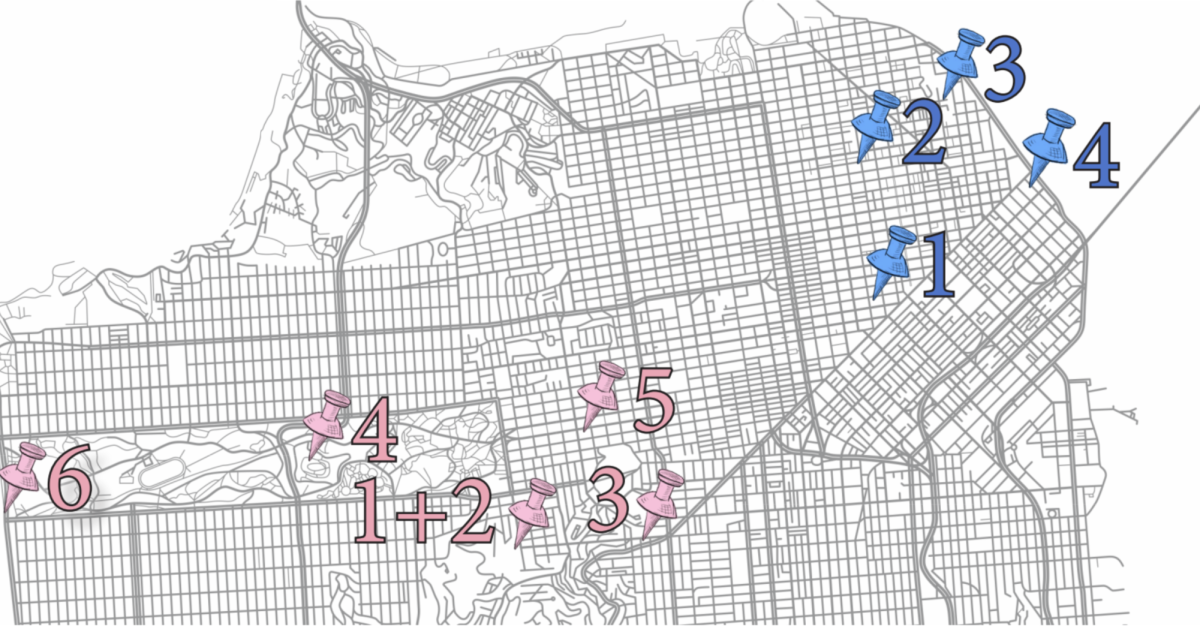

According to the results of the 2014-2015 California Healthy Kids Survey, by senior year, 59 percent of PHS students reported drinking at least one drink of alcohol in the past 30 days, and 45 percent reported binge drinking, which was defined as five or more drinks in a row.

Compare statistics from PHS to similar numbers from colleges across the country: 60.3 percent of college students aged 18 to 22 reported drinking, and 40.1 percent reported binge drinking, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) in 2012.

Nationwide, the number of students who reported alcohol usage before entering college is at its lowest point in 30 years, according to a University of California, Los Angeles, survey of 153,015 college freshmen at a wide variety of four-year institutions. In 2014, 33.5 percent of students reported that they “frequently” or “occasionally” drank beer, a precipitous drop from 74.2 percent in 1981. A similar fall is seen in wine and hard liquor consumption rates from 2014 to 1987: down to 38.7 percent from 67.8 percent.

Students who drank frequently in high school were less likely to think they would earn at least Bs in college and join student organizations, according to the University of California, Los Angeles survey.

Students who drank frequently in high school were less likely to think they would earn at least Bs in college and join student organizations, according to the University of California, Los Angeles survey.

Binge drinking in college can start in high school: high school students who reported drinking at least once a month during their senior year were three times more likely to become binge drinkers in college than other students, according to an article in the Journal of Adolescent Health by researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health.

From Piedmont to College

In college, a combination of autonomy from parents, a wide variety of social events, and peer pressure leads to more drinking compared to in high school, said UC Berkeley freshman and PHS graduate Daniel Lin.

“Drinking is part of the social norm, but people respect the fact that studying is more important and that everybody has to work hard,” Lin said.

Stanford freshman and PHS graduate Hayden Payne expressed a similar perspective, citing the presence of other social options and a relatively lax university drinking policy as reasons for more moderate levels of drinking at her college.

“College students approach drinking from a more mature perspective,” Payne said. “Alcohol isn’t your only way to have fun, so people don’t need to make a big deal out of alcohol here. There’s no pressure and more of an attitude of openness.”

To Payne, Piedmont has an unhealthy culture surrounding alcohol — one where 60 percent of seniors report having been very drunk or sick after drinking and 44 percent report having driven while intoxicated or been in a car driven by somebody who had been drinking, according to the California Healthy Kids Survey.

Part of what contributes to high drinking rates at PHS is that students often can afford to buy alcohol. The median household income of $207,222, according to recent census data, and 86 percent of PHS seniors say that it is “fairly” or “very easy” to obtain alcohol, according to the California Healthy Kids Survey, which corroborates Lin’s conclusion.

“A lot of parents [in Piedmont] don’t really regulate drinking,” Lin said. “Some even encourage it because they know that eventually they’re not going to be around and they won’t be able to control it.”

Evaluating predictors can help explain high drinking rates in Piedmont: White males with high parental education and socioeconomic status consistently have the greatest rates of binge-drinking, according to an investigation from researchers at the University of Michigan and Pennsylvania State University. The residents of Piedmont would appear to fit the bill — the population is 71.5 percent white and 82.7 percent of those age 25 and older havehaving a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to recent census data. — would appear to fit the bill.

However, according to the California Healthy Kids survey, gender statistics in Piedmont contradicts predictors: Female seniors were 28 percent more likely than male seniors to report current alcohol use, 26 percent more likely to report getting very drunk or sick after drinking, and 11 percent more likely to report binge drinking.

“In Piedmont, girls are encouraged to drink more than guys are,” Payne said. “Drinking can be associated with how popular or fun a girl is.”

In the end, although drinking and binge drinking rates for seniors at PHS mirror rates in college, according to the California Healthy Kids survey and the NIAAA, high school and college students approach alcohol differently.

“Sometimes Piedmont feels like a bubble and people use alcohol to compensate for their lack of experience,” Payne said. “Honestly, that seems kind of silly now.”

A Researcher’s Perspective

When looking at facts and statistics about adolescent drinking habits, it is hard to prove causation over correlation in research, and there are a multitude of factors that affect particularly research on humans, making it particularly hard to come to concrete conclusions. Graduate student researcher at UCSD Tam Nguyen-Louie can attest to this.

“When you read articles online or in the news about how ‘research shows this’, and when you go back and read the actual research, it tends to be, ‘Well, we think this is happening and these are the statistics and these are the caveats and limitations,’” Nguyen-Louie said.

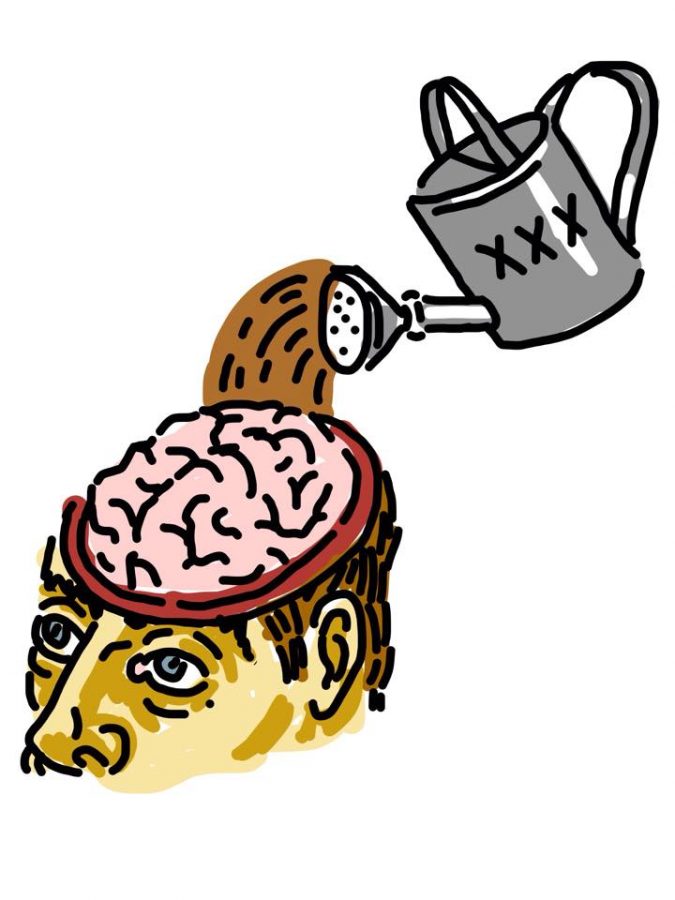

In the lab Nguyen-Louie works at, she researches how alcohol and other recreational drugs affect the brains of adolescents (people aged 12 to 25). To do so, she uses imaging data, looking at MRI tests of brain structure or different areas of the brain’s activation in response to external stimuli, as well as neurophysical testing of cognitive function, which measures things like visuospatial abilities (how our brain sees objects and the space between them), working memory and executive functioning, which is higher-order functioning like impulsivity and being able to switch tasks.

Research Studies over the past few decades on this subject suggests with a certain level of confidence that adolescents who drink heavily tend to do worse than abstainers on cognitive tests over several years, Nguyen-Louie said.

“The point of contention [for researchers], where it gets muggy, is how that happens,” Nguyen-Louie said.

A large factor that comes into play in Nguyen-Louie’s research is the adolescent brain. Even up until a person’s late twenties, when the rest of their body has stopped growing, their brain essentially prunesis essentially pruning itself to become more effective and formsforming new connections within neurons, Nguyen-Louie said.

Further complicating the matter, the frontal lobe of the brain, which is responsible for higher cognitive function, like making decisions and controlling impulses, is developing at a different rate than the brain’s rewards center, which creates urges for food, alcohol and sex, Nguyen-Louie said.

“You can’t just compare two drinkers at different ages because they’re at two completely different stages of maturation, just by their brains alone,” Nguyen-Louie said.

Even more important than brain development, research depends on the frequency and quantity of drinking, even the physiology of the drinker. Researchers therefore cannot control for age, so no evidence exists of precise shifts in how alcohol affects the brain from high school to college.

“It’s really difficult to say that if somebody drinks this at that age, this is going to happen,” Nguyen-Louie said. “It’s really not that clear-cut, especially when you get into the nitty-gritty details of research.”

Another of these factors that Nguyen-Louie is currently examining is how the age of onset, or when a person starts drinking, affects their cognitive functioning. Although she has not completed the project, her preliminary results, using a smaller sample size, suggest that the earlier that somebody begins drinking, the worse their cognitive functioning is, especially in the domain of memory and executive functioning, she said.

“What I’m talking about is not something you can look at somebody and see,” Nguyen-Louie said. “It probably won’t be reflected in their GPA, it doesn’t manifest itself in such a dramatic way.”

College students have not been drinking their whole life, so the effects are often not as obvious in adolescence. But that is not to say that heavy drinking cannot have an obvious effect: for example, research on Korsakoff syndrome suggestsfinds chronic short-term memory loss results fromas a result of heavy drinking for more than a decade, Nguyen-Louie said.

“The cognitive changes that we do see in adolescents are concerning to us because it says that, ‘Hey, even if you’re a pretty highly functioning, well-to-do twelfth grader or freshman in college, and you might not have any noticeable problems [from drinking], there’s something going on cognitively,’” Nguyen-Louie said. “So imagine what happens if you continue this trend for the next twenty years of your life.”