The students furrow their brows, eyes focused intently upon their papers. Though they are separated by dividers, their stress permeates the room.

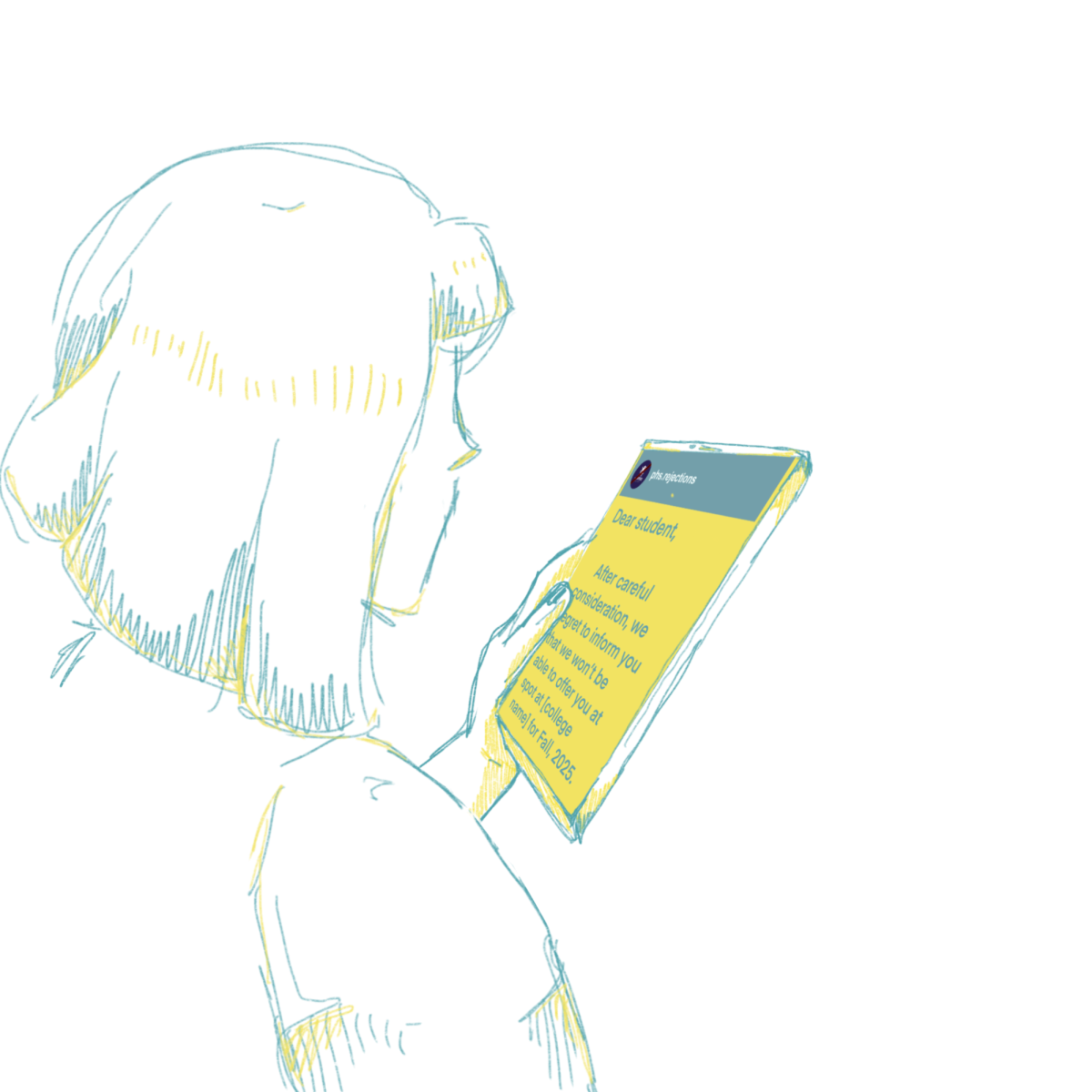

This is a familiar scene for all of us. The test, the grade, the pride, the disappointment. For many students, school becomes a flurry of textbooks, tedious problems, stressful quizzes, and daunting midterms. It becomes a list of tasks to check off, easy to disconnect from, easy to despise.

Topics that may inspire passion and excitement for some unfortunately become tainted with a dull and monotonous feeling.

This is not to say that the way we learn now is a completely invalid method. The issue of quantifying students’ understanding is complex, and the system in place now which values individual work sets a system for clearly assessing students’ proficiency in various skills. We recognize the value in the basic methods we have learned for solving problems individually. We recognize the value of learning to generate our own ideas and make connections within our own host of knowledge.

However, we believe that students would benefit from a shift in our education system, in which a greater focus is placed on group learning and complex problem solving with real-world connections. While Common Core is already a step in the right direction, we believe this goal could be achieved by the implementation of more collaborative, real-world type projects.

For instance, in U.S history, we make a poster that is representative of the contrast between the 1920s and 1930s. While this is an effective way to learn the history of the time period, the project does not require students to extend their understanding beyond the past, or consider its relevance to their own lives. This sort of disconnection can often lead to a feeling of indifference among students.

Instead, we could be assigned a collaborative task, such as designing our own government reforms for the 1920s aimed at preventing the Great Depression from ever occurring. To do this, we could examine historical context, while also working in a group setting to defend our own ideas and compromise. This type of learning would combine the traditional research-based element of the poster project with the complexity and stimulating nature of cooperation.

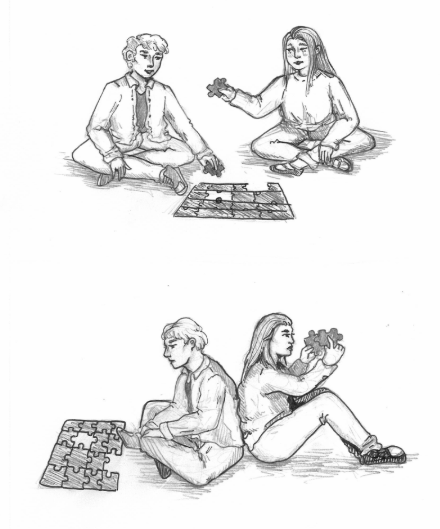

We believe that these collaborative skills can be applied to many settings outside of our formal education. Working with others, we not only complete tasks more efficiently, but also more thoroughly. While individual knowledge is important, many complex real-world problems can often only be solved when individuals combine their skills and perspectives.

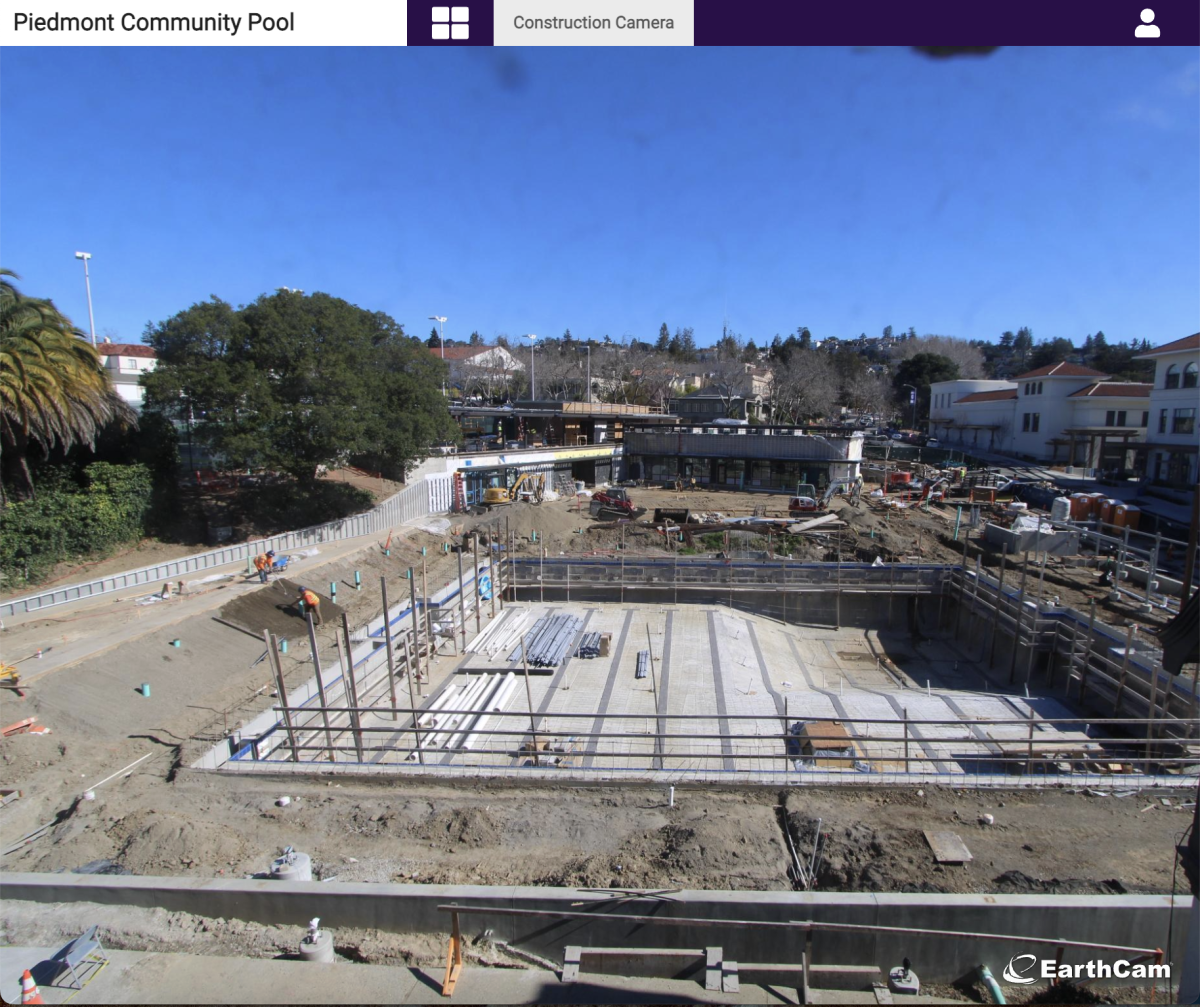

The changes to include more skill-oriented learning do not have to be drastic. We already have projects that incorporate some of these ideas, such as Urban Plan, a group project in which students design an economic revitalization for a hypothetical neighborhood. Using existing models like these would encourage students to truly engage with the material they learn, as well as improve their communication and leadership skills.

Let’s take away the dividers, start some conversations, and create connections with our work and each other.