Critical Race Theory in High School Classrooms – Fact or Myth?

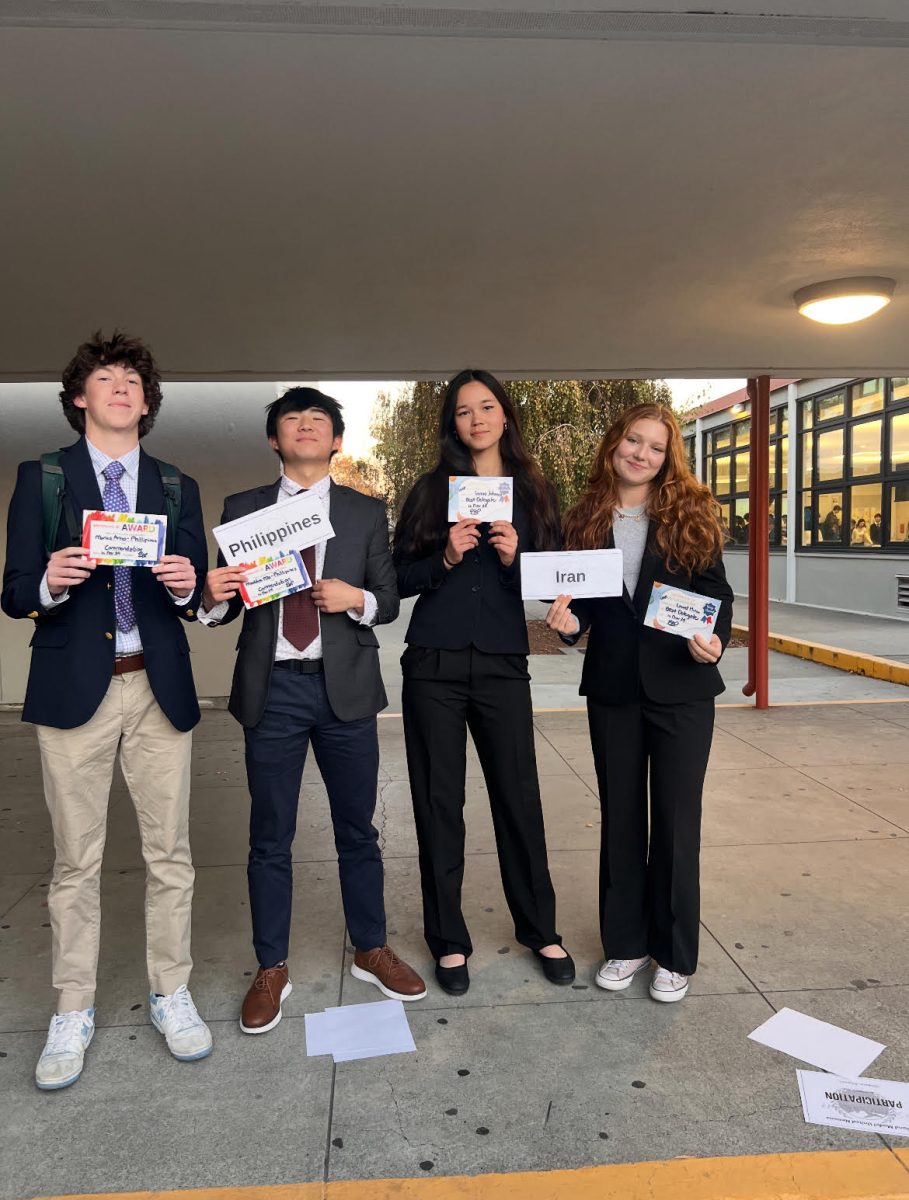

David Keller teaches his students in his AP US History class

Dec 7, 2022

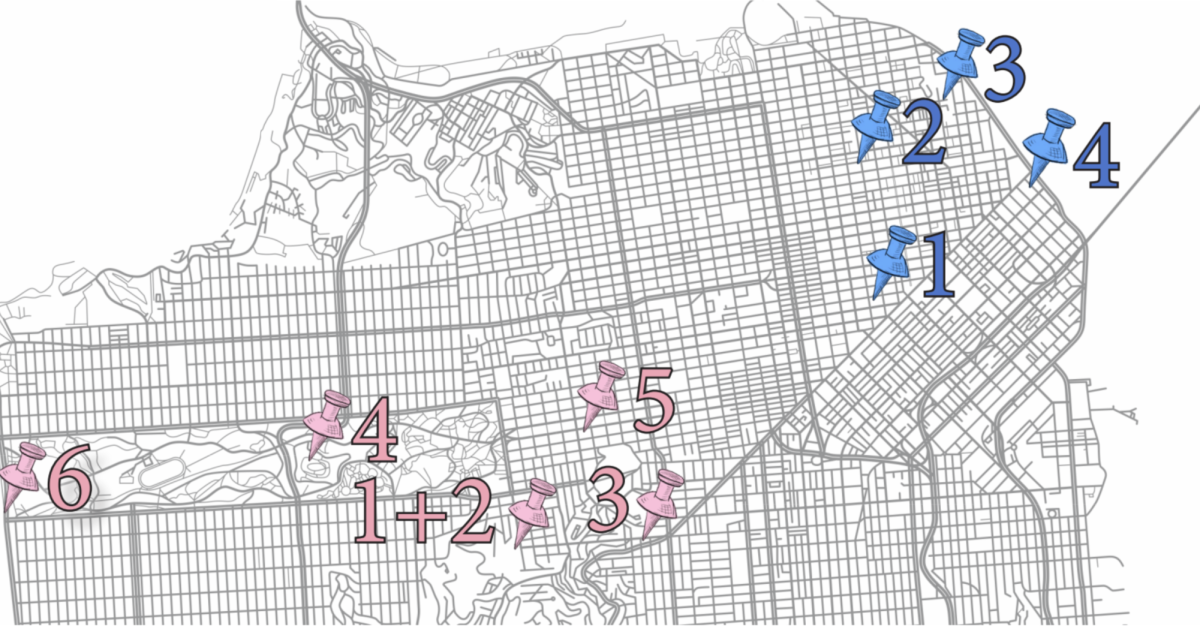

CRT. Critical Race Theory. The term is thrown around at school board meetings, mentioned in pointed questions to Supreme Court nominees, and included in conversations about race. In recent years, the subject of CRT has been a focal point in discussions about how American history is taught at the high school level. However, many people don’t fully understand what it is.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, Critical Race Theory (CRT) is the belief that race is a social construct invented for the purpose of the oppression and exploitation of people of color. CRT scholars believe that racism is embedded in the law and institutions of the United States to maintain inequity between white people and people of color, African Americans in particular.

While most students are familiar with the term, many are unable to define it, or even identify if it is included in their classes. Because of its complexity and depth, CRT is rarely taught at a high school level, and usually only taught in law schools or masters programs, according to Interim Superintendent Dr. Donald Evans. Although high school students may be able to grasp small parts of the theory, even masters students struggle to comprehend the complete theory, Evans said.

Although conversations about race and racism in the context of American history and the current social climate are very prevalent in most PHS classrooms, much of the discourse is not actually CRT.

“It is highly unlikely that [high school] students will be studying about and making the connections between systemic organizations that maintain systemic racism,”said Director of Diversity Equity and Inclusion Dr. Vanden Wyngaard. “There is no one to my knowledge teaching CRT at the high school, as it is taught at the collegiate level.”

While most high schoolers cannot hold in-depth conversations about CRT, some Piedmont teachers try to integrate aspects of the theory into their teachings.

AP US History teacher Dave Keller doesn’t teach CRT, but instead has his students view the history and decisions of our country from the different perspectives of both historical figures and historians.

“What I try to do is pose moral questions and ask students to make a judgment on those moral questions,” Keller said. “I try to take my bias out of it so that people can legitimately, without a feeling of being pushed one way or the other, make it a moral decision [on historical events].”

Keller has provided his students with different types of writings, including the 1619 and 1776 projects, which were referenced at the November school board candidate student-led panel. The 1619 Project consists of a series of essays by Nikole Hannah-Jones that work to reframe how we talk about US history by putting black Americans and the consequences of slavery in the direct center of our nation’s narrative. After this project was published, former president Donald Trump commissioned the ‘1776 Project’, a report that aimed to promote “patriotic education” by framing US history in a way that puts America and its founders in a more positive light. Bills in Arkansas, Iowa, and Mississippi have been introduced that restrict funding to any school districts that use the 1619 project in their curriculum, according to Education Week.

According to Keller, reading and discussing banned works allows students to think critically and discern why it was or wasn’t restricted.

“I think that the marketplace of ideas is strong enough to be able to allow people to really make judgments for themselves,” Keller said.

Other departments hold similar discussions. In the fall of 2019, Gabrielle Kashani introduced Ethnic Studies as a course in Piedmont High School after feeling the need for a class that focuses on people of color. Hayley Adams took over the class this year. The course explores different ethnic minorities and communities and the historical and current struggles they have faced.

“We felt like there was a specific need to teach a class that 100% focuses on race in the United States. We wanted to augment the US history courses which aren’t so focused on race, and also counterbalance the disproportionate focus on [eurocentric perspectives],” Kashani said.

Similarly to Keller, Kashani included excerpts of the 1619 project in her curriculum, which she said she would categorize as CRT. According to Kasahni, teaching her students the reality of American history by adding multiple points of view on historical events that get lost in most other history classes is important to her.

“We have to have an honest look and conversation about our country’s origins and the role that race played in those origins — which was setting up a racial hierarchy, unique to pretty much anything else that happened in the world,” Kashani said.

PHS teachers aren’t explicitly teaching CRT, but they are cultivating environments that provide students with foundational knowledge on race and racism so they are better equipped for future conversations about those topics.

While certain teachers are including small aspects of the theory in their lessons, high school students are not learning CRT to the full extent of what it is. Teachers are providing their students with an American history that includes all different points of view.

“For me, what is important is that we give [students] the chance to critically examine those ideas, critically understand those ideas, and make decisions in how [they] think about and view the world,” Vanden Wyngaard said.