Examining the Value of the Mexico Trip: the Case Not to Go

Dec 8, 2022

After a two year hiatus due to COVID-19, the Piedmont Community Church hosted its annual Mexico Mission trip in Spring of 2022. Over 170 students and adults built a total of 12 houses for residents of Tijuana, Mexico. This upcoming year, the church plans to send 15 teams to build even more homes for poverty-stricken families. Although building houses for underprivileged families is admirable, this particular type of missionary work is not the most effective way to bring about change for the targeted communities.

The volunteers who embark on these types of trips spend unmistakable time and effort on their missions, but allocating time and resources to train high school students with no construction experience to build homes is inefficient. If efforts were instead made to increase education about cyclical poverty, it might be more widely understood why these types of trips can be counterproductive.

Repeated giving of this nature fosters a culture of dependence upon external aid in impoverished communities rather than facilitating internal support and empowerment. This has been a pervasive problem for centuries, particularly between the United States and Latin American countries. When Americans with no regional cultural understanding attempt to manage and control local issues, it perpetuates a feeling of powerlessness within communities that is not conducive to growth. Creating an unhealthy reliance on foreign aid and resources can devalue domestic programs and continue to fuel the cycle of poverty.

Additionally, trips like these propagate the narrative that underprivileged people are inherently helpless–not only to the families being served, but also to the students participating in these missions. These short-term trips leave the students satisfied in having done good deeds, but fail to educate them on the complexities of the communities they strive to help. Income inequality, inadequate education, climate change, and limited government capacity are just a few of many factors that exacerbate poor living situations. Trips like the Mexico Mission attempt to treat only a symptom of poverty, rather than inspiring structural change by targeting the actual roots of the problem.

Ironically, the selflessness that students devote to these missions can in some ways be rather self-serving. In committing these acts of service, privileged individuals sometimes leave the experience relieved of the guilt that they carry about their own affluence, convinced that they have made a sufficient contribution to aiding those less fortunate. Not only have they not done so, they have emerged less likely to engage in true service. Many Piedmont students report feeling satisfied that they have “done their part” in paying back their privilege in taking this week-long trip.

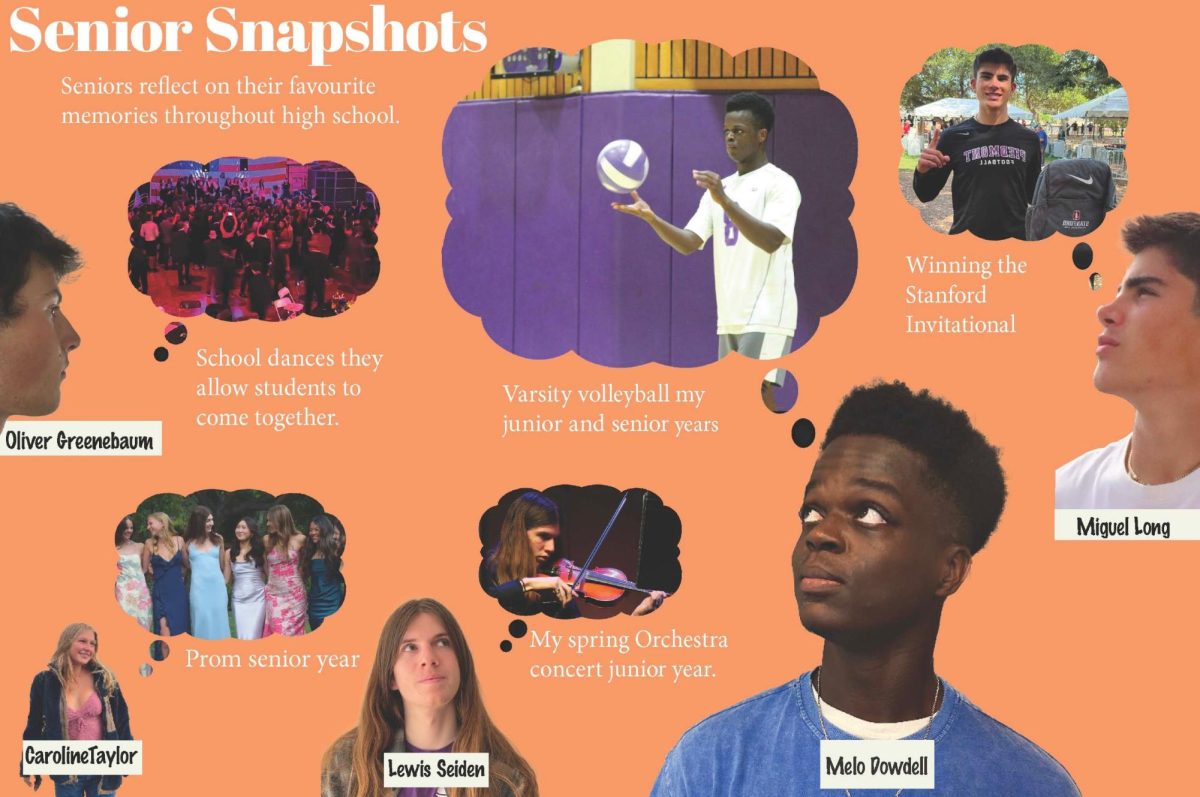

In Piedmont, there is a unique social element to the trip that begs further contemplation. It is well-known that the primary motivating factor for the vast majority of participating students is the social aspect of the trip. Veterans of the mission cite team parties, sweatshirts, and team-building activities as highlights of the mission. Whether you are participating in the trip or not, the pre-Mexico-buzz is impossible to avoid. As soon as the participants get their team assignments, they begin hosting bonding parties and chatting about their inter-team drama and sweatshirt designs. Somehow, the glaring irony of spending large sums of money on themselves in preparation for a service trip is lost upon many. Along every step of the way, there are indications that service is not the focal point of the trip.

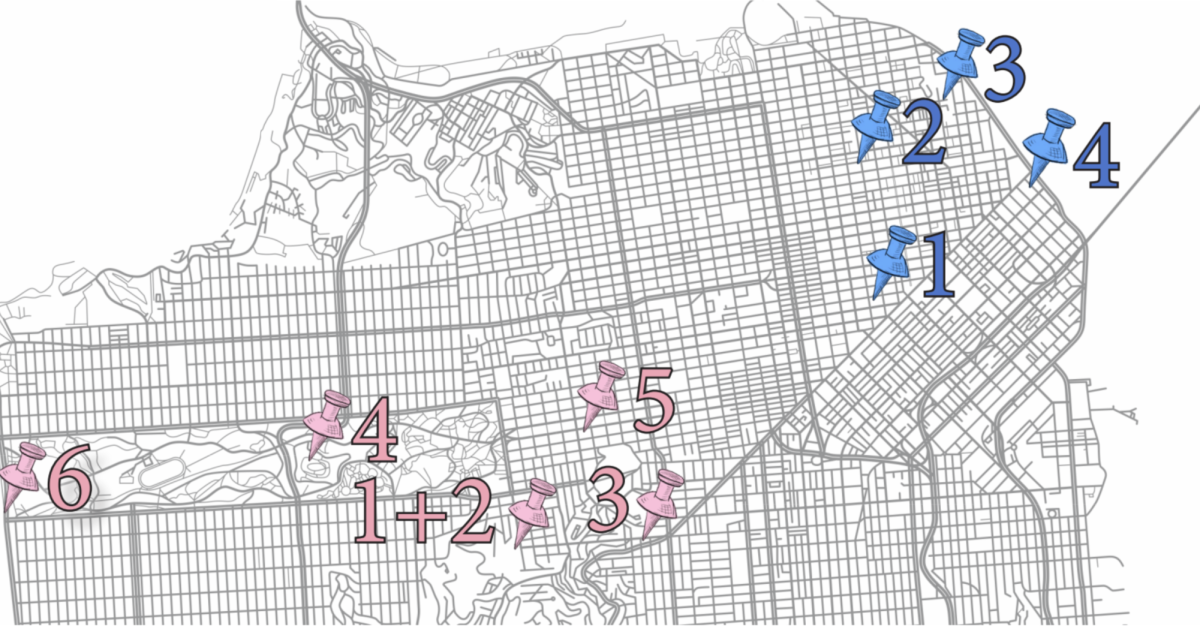

Some advocates of the trip argue that while it may not be efficient, it is worthwhile, because students are provided an opportunity to catch a glimpse into the lives of those less fortunate. In actuality, this should not be difficult for residents of Piedmont who are surrounded by neighborhoods where many of the residents fall below the poverty line. No student in Piedmont needs to travel more than a mile from their home to “experience” a tremendously underserved and underprivileged community. There are an abundance of local opportunities to serve people in need, an opportunity in which the students of Piedmont seem far less interested. Last school year, ASB had to extend their annual food drive for the Alameda County Community Food Bank (ACCFB), three times in order to meet their goal. It is embarrassing to suggest that students need a curated, enticing experience to learn how lucky they are, or that they need to travel to Mexico to find disadvantaged people to help. Many organizations like the Piedmont Community Service Crew (PCSC), the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul and the ACCFB offer weekly opportunities to serve the Bay Area community that make a direct positive impact on the lives of locals, like the Mexico trip intends to. For students interested in participating in a large community service project with friends, PCSC hosts a nearly identical annual project in which students take on group construction projects in Oakland.

International service trips are not always harmful. Productive service trips should be centered around empowering local leaders that are intimately familiar with the issues in their communities rather than foreign volunteers who have never experienced poverty. Organizations like Doctors Without Borders utilize the skill of professionals to promote self-perpetuating growth in communities in need. In service of all kinds, volunteers should have an accurate and humble view of their role in improvement, and make sure that the work focuses on the people they are helping, rather than themselves.