Failing to reach your goals

My fingers whiz across the keyboard. Clack clack clack. Done. I click print and listen for the rumble of the printer coming to life in the other room. I grab my essay from the tray, planning to proofread it during dance rehearsal. In that instant my phone vibrates. It is an alert to remind me to write that speech for the Swim Team Banquet tomorrow night. I set another reminder, I can just do it later. My mom calls from the other room to remind me to write that email to the National Leadership Conference. I tell myself I can do it later.

But what if later never comes?

“I feel like no matter what, I can’t help but have high expectations [for myself],” junior Walter Le Duy said. “Generally the stuff you have high expectations for are the most important. The stuff I really want to do well in, I set my bar really high for.”

High expectations are helpful because they push you to succeed, sophomore Eliza Lucas said.

“I think if you have high expectations you’re more likely to get back up and try again if you fail,” Lucas said.

However sometimes, high expectations do not always have the greatest benefit when it comes to failure, something both Le Duy and Lucas have noticed.

“[When I don’t succeed,] I don’t cope well,” Le Duy said. “I try to move on with it without thinking about it and I might not really learn.”

Lucas said that outside pressure can also create stress.

“My whole family, they’re all very successful, so they set the standards pretty high,” Lucas said. “It helps me push myself, but sometimes it’s too much.”

So how do we push ourselves to succeed, yet manage our expectations in the event of failure? Erika Carlson, a Bay Area mental skills coach for young athletes, was able to provide some insight.

“Oftentimes, athletes rely too much on winning as a source of confidence,” Carlson said. “Some kids have been able to rely on themselves through physical means their whole lives, but are unable to cope with the mental pressure when it becomes too great. We help them learn how to prepare properly for competition.”

Carlson employs a variety of skillsets in her training of young athletes, all of which she says can be extended into real life.

Self Talk, the practice of training the thoughts that go through an athlete’s mind in the moment of competition, can help impact performance under pressure.

Another method is visualization, practicing by thinking through each routine in detail and feeling the emotions as though it were actually happening.

A majority of professional athletes use these skills to better their competition performance, Carlson said.

She also said that it is important for people to learn how to make plans for their goals. People should not make just one goal, but rather a whole series of goals that will lead them to the outcome they are looking for.

“For example, first I have to figure out how to get to Point B, and after that, Point C, before I can reach my goal of Point D,” Carlson said. “So it’s much more of a pathway versus expecting an outcome to happen.”

Carlson said that this form of setting goals is more helpful than making one large outcome for yourself.

“This way, there are multiple goals that must be met before the desired outcome,” Carlson said. “With short-term goals, a person is constantly working to achieve something, and by achieving each goal bit by bit, they are working towards their long-term goal.”

Failure is something Carlson must inevitably help her athletes deal with and she regards it as just another skill to help them grow.

“Failure is really important to long-term success. Failure happens in life – you don’t make the team, you don’t get the A, you don’t get the feedback you wanted. Failing is a life skill,” Carlson said. “In only true adversity can you really learn how to deal with adversity – you have to have failure so you can know how to deal with it.”

Carlson said that athletes mostly come to her because they are too anxious before competition, though there are different ways that people cope with pressure.

“The people who don’t work well under pressure might be more likely to be more diligent, so as to avoid situations of pressure,” Le Duy said. “My sister does not work well under pressure, so she always plans stuff out really well.

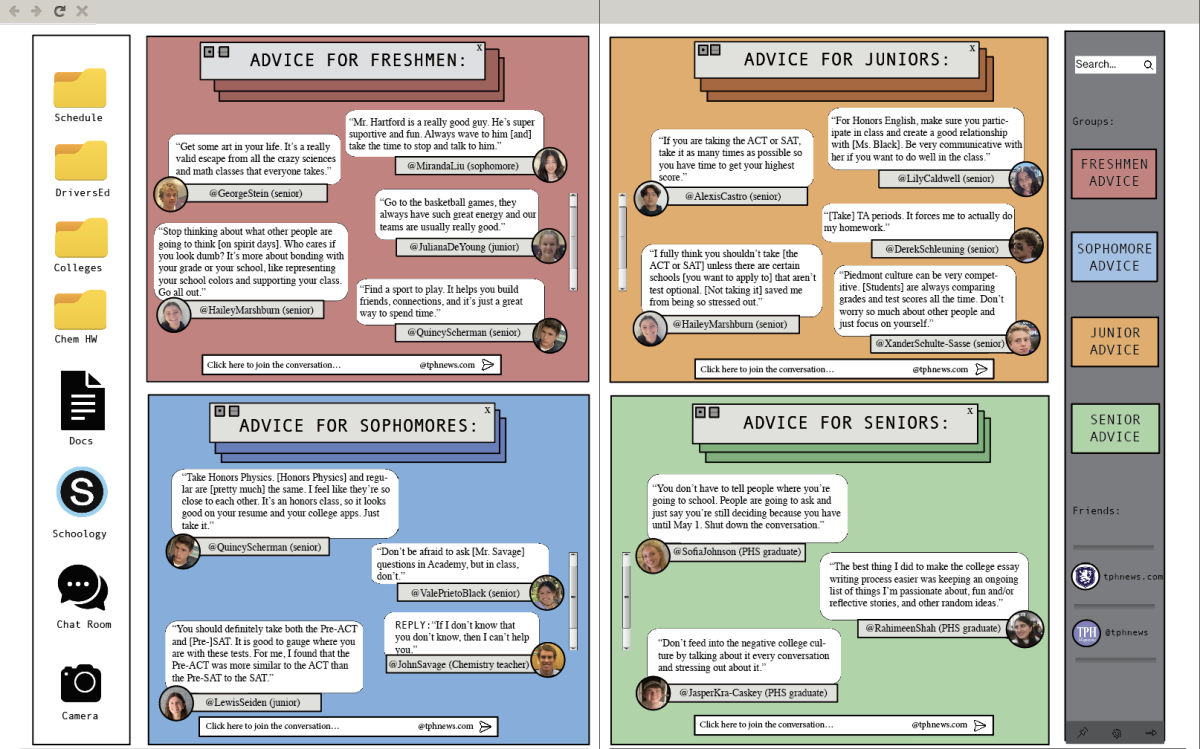

Peer advisor senior Samantha Lai said that the best way to help students through the pressure is just to listen.

“That’s what we are here for, as peer advisors,” Lai said. “Sometimes someone to listen is all you need to alleviate stress and refresh yourself and keep going full speed.”

Lai recently spoke with sophomores in social psychology classes about how academic goals and the inherent competition between students affects relationships with friends.

“I could definitely relate to what our social psych kids were saying, because I know I hold myself to high standards and put a lot of stress on myself to meet them,” Lai said.

Lai has noticed that the biggest source of pressure on students almost always comes down to school stress, noting that it is the root of a lot of the problems that kids have to deal with.

“The most important thing is just to be able to recognize how far you already have come, how much you already have done, and not get too hung up on what you haven’t accomplished,” Lai said.

Flunking a test

As your teacher hands back your recent test grade, you agonize over how awful you did this time. Hands shuddering, you wince as you put the test into your backpack, feeling the sweat and heat of your rising body temperature. Later at home, you take out the test and flip it over. Your eyes wildly scan across the page before locking onto the letter grade. It’s a C+. You think you screwed up big time, and now no college will to want you.

At Piedmont High School, not being able to reach a desired grade can be stressful or depressing. However, many teachers and students believe doing bad in a class is not entirely negative and can be used in a positive and constructive manner. Sandy Brod, director of the College and Career Center, said that many of the most successful women and men were not academic superstars.

“A lot of entrepreneurs and self-starters have not had a good track record,” Brod said. “That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t, but’s it’s not the end of the world if you’re not a perfect A-student at PHS.”

Brod believes that because parents are so emotionally involved in making sure their kids are happy, they do not want them to ever fail, even though doing so can teach students how to improve for the future.

“It’s good for them to fail because they pick themselves back up and keep going,” Brod said. “I would encourage some parents to transfer responsibility to their children.”

Math teacher Doyle O’Regan said that he has benefitted from his own academic failures.

“In college, I failed Econ 113 and had to retake it,” O’Regan said. “I made sure to do well after that.”

O’Regan believes that it is good to experience failure while growing up.

“Experiencing failure a number of times reveals your character and how you handle those adverse situations,” O’Regan said. “It can shape your attitude and make you a little thicker-skinned and tougher.”

Junior Brian Ou said that just failing once and reflecting upon it does not make you instantly better.

“It’s a constant process, and in order to really improve yourself from a bad position, you’re going to have multiple failures,” Ou said.

However, senior Sierra Yeh believes that, in an emotional sense, it is hard to take failure positively.

“Doing bad in a class is always frustrating and depressing,” Yeh said. “But you can learn lessons such as not procrastinating and staying organized.”

Brod said that since parents are often focused on competition for colleges, it becomes hard for parents to judge whether or not to let their kids to take responsibility.

“When kids do bad, it’s just another chance to get better at it, just another challenge for them,” Brod said. “But, failure is not a necessity. It can happen and help you, but there are many kids who do many wonderful things who don’t fail.”

Junior Carson Armstrong agrees that failure is not a necessity to succeed.

“I would rather succeed my whole life in every way possible than to fail once,” Armstrong said. “But since that would be impossible, I try to make failures beneficial and learn from them.”

Brod said that some colleges penalize kids if they start doing bad in junior or sophomore year, but other colleges are more thoughtful and read kids out differently.

“The big schools, the UC’s, they’re not going to treasure failure, they’re going to treasure academic success,” Brod said. “The private schools and smaller institutions value failures, and when you tell them the process of how you failed and learned from it, they respect that.”

Brod said if a student is able to quickly pick it back up after doing badly, colleges will see that and take it positively.

“All colleges like an upward trend,” Brod said. “What’s important is realizing the reasons you did bad and improving on them.”

O’Regan also said that the issue is not what you do poorly on or fail at, but more of how you respond to it.

“Some people just totally melt down from failure, never learning from their experiences or adjusting,” O’Regan said.

Armstrong sees failure in a positive light.

“Whatever happens in the past happens, you can’t change that,” Armstrong said. “But you can change the future and you can make failures benefit you.”

Forcing meaningless rewards

hat’s shiny, golden, and worth absolutely nothing? Hint: everybody got one for tee ball. With so many people desperate for rewards, you would think that “Everybody Gets a Prize” is the American motto.

Yet this trophy, this pretense of success, is enough to satisfy the vast majority. The prospect of reward continues to drive people in all facets of their life.

“Rewards really do help,” sophomore Megan Deutsche said. “Even little things motivate you a lot. It encourages you to do better.”

And most people would agree that, yes, rewards do motivate people, but when is enough enough? When does a prize cross the line from a hard-earned award to yet another cheap plastic little kids’ trophy? Admittedly, it is now hard to differ between the two.

“I was on the B-team and at the end of the seasons, the coaches were like, ‘You were on the team. Here’s a prize,’” sophomore Elie Docter said. “I just thought, ‘Uhh, we didn’t even win a single game.’”

Deutsche feels the same way.

“[They’re] trying to make you feel like, ‘Oh, you did well,’ but it doesn’t really mean anything,” Deutsche said.

Junior Robbie Diaz, however, said he believes that people should be rewarded for putting in effort and dedicating time to a task.

“I think people should be rewarded for their effort,” Diaz said. “I don’t necessarily think success should be determined on a pass or fail basis.”

But whichever opinion you agree with, all parties understand that overcoming failure is a vital part of maturing.

Docter recalls a particularly traumatizing experience she had in seventh grade.

“I was making pretzels and needed them to rise, but it was rising for like an hour so it was really light,” she said. “My pretzels weren’t working and it was like 11:00 at night so I was getting really frustrated, and I just had to throw it all away.”

Overall, though, she feels that she has grown through the failure.

“Pretzels are a learning experience,” she said.

Likewise, Diaz feels that every mistake is a lesson.

“I try not to let numbers or letter-grades decide who I am and rule my life,” he said.

Finding a grit

white picket fence, steady income, home ownership and a family of four was once laid out as the American Dream in the 1950s. In that time, the American youth grew up seeking to achieve that, their image of success. Fast forward to 2014 – what is, or what is not successful, no longer has a set definition.

Many look to income to try to measure success. In high school, a GPA or SAT score might be looked at as a measuring tool for success, but does a low grade point average indicate life failure? Individual people have individual ideas of success, and therefore individual ideas of failure.

The New York Times columnist and correspondent for The Atlantic Jessica Lahey said that in high school, she was a perfectionist who saw a low grade as the end of the world and as a commentary on her worth.

“Even in college and graduate school, I was ashamed of my lower grades and never viewed them as a learning opportunity, but as a condemnation,” Lahey said.

It took a lot of work, but Lahey has tried to shift over to a growth-mindset, in which she recognizes that intelligence is malleable.

“The harder I work, the smarter I get,” Lahey said. “The challenges, even the ones I fail at in the first or second attempt, are valuable and make me a smarter person and more competent at what I am doing.”

Psychologist and former seventh grade teacher Angela Lee Duckworth discussed the idea of what makes someone successful in a TED talk called the “Key to Success? Grit.”

“Some of my strongest performers did not have stratospheric IQ scores, and some of my smartest kids weren’t doing so well,” Duckworth said.

Duckworth left the classroom and studied children and adults in various settings to see who would become successful. She and her researchers observed who would stay in the military academy, who would graduate from school, who would get a sales promotion, and through this observation discovered that the successful ones were the ones with the most “grit.”

“Grit is passion and perseverance for long term goals,” Duckworth said. “Grit is having stamina, sticking with your future day in day out. In our data, grit is unrelated or inversely related to measures of talent.”

For Lahey, success is learning – trying something new and figuring out if it is something she likes to do, and if it is, becoming good at it. She said the key to success is learning how to rebound from mistakes.

“You could be the best math student in the world, but eventually it’s going to get hard,” Lahey said. “Eventually, the answers won’t come easily, and it’s how you deal with not being able to find those answers right away that determines whether you ultimately fail or succeed at your goals.”